Archaeologists from Poland’s Jagiellonian University (JU) have discovered an ancient Native American calendar at the Castle Rock Pueblo archaeological site in western Colorado that houses the remnants of an ancient settlement. While the oldest petroglyphs found date to as early as the third century AD, JU researchers have found works in previously unstudied rock panels created in the 13th century, when the site was at its peak of activity. The leader of the Polish research team, Radosław Palonka, considers these findings to be the start of a new process of discovery, combining cutting-edge mapping technology and collaboration with local Indigenous communities to better understand the area.

Castle Rock is the largest village within a sprawling ancient settlement complex in Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park. The villages, carved into rock faces in the area’s many canyons, are characteristic of the Pueblo culture that flourished in the 12th and 13th centuries. After more than a thousand years of inhabiting the region, Pueblo peoples developed advanced techniques for architecture, combining intricate rectangular rooms made from adobe into fortified terraced structures. Favourite locations for construction were defensive positions, including hilltops, mesas, and the steep rock ledges present in the Castle Rock Complex.

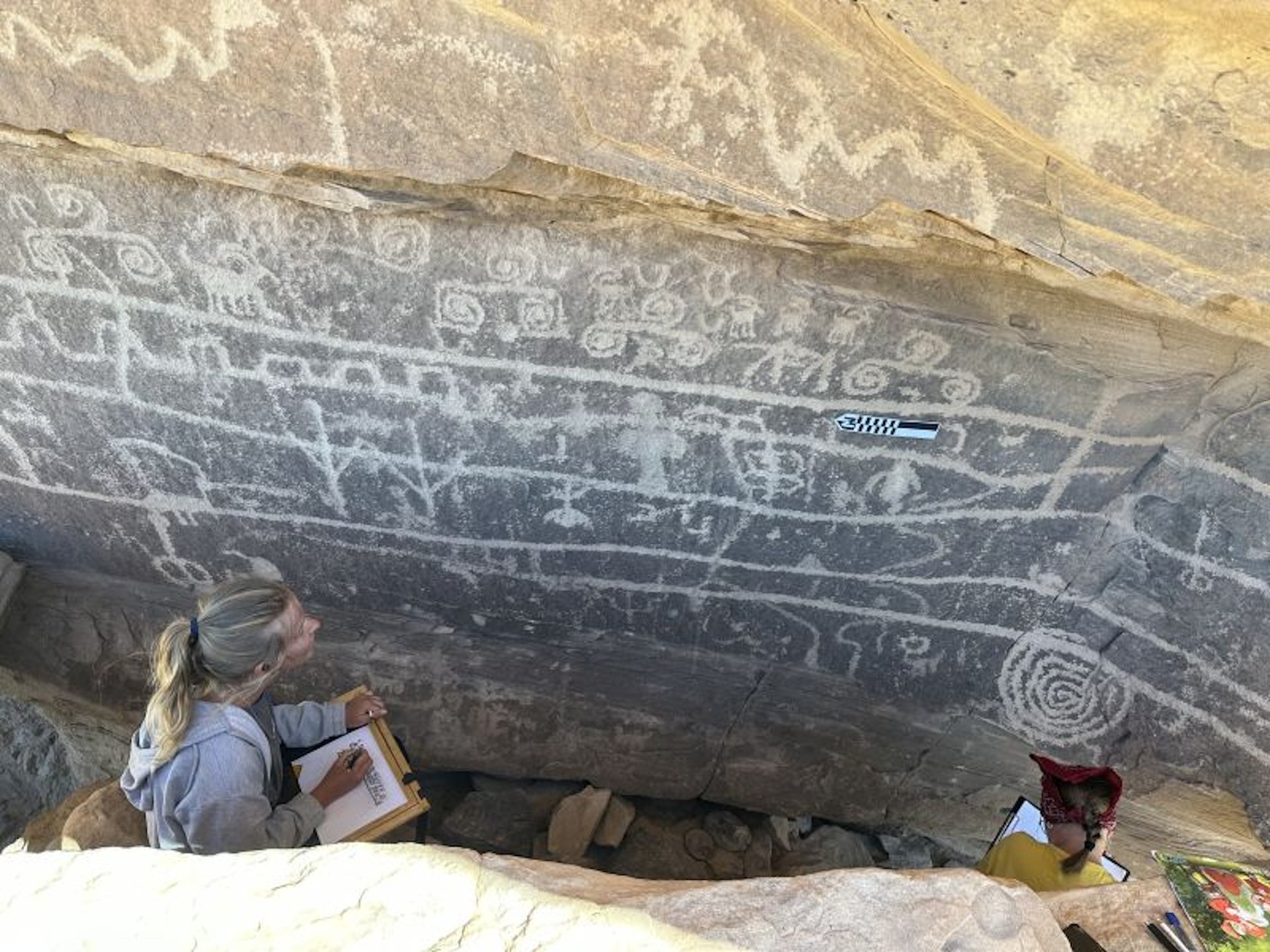

Another ubiquitous trait of Pueblo sites are their inhabitants’ rock art, depicting scenes of everyday life, complex geometry and astronomical subjects. The discoveries of the JU archaeologists centre around these petroglyphs, carved into ledges previously overlooked or considered inaccessible. Among the galleries of rock art discovered are carvings from the Basketmaker Era of the first centuries AD, in which predecessors to the Pueblo people carved warriors and shamans. The majority of findings, however, come from the peak of Pueblo culture in the 13th century, in which the large population occupying nearby adobe structures carved shapes and spirals up to a metre large for suspected religious purposes. Later carvings from the Ute tribe are also present, depicting narrative scenes of hunting, and the Post-Columbian introduction of horses to the region.

Researchers examine ancient petroglyphs in Colorado's Mesa Verde National Park Jagiellonian University

“I had some hints from older members of the local community that something more can be found in the higher, less accessible parts of the canyons. We wanted to verify this information, and what we found surpassed our wildest expectations. It turned out that about 800 metres above the cliff settlements there are a lot [of] previously unknown petroglyphs. The huge rock panels stretch over 4km around the large plateau,” Palonka said in a statement. “These discoveries forced us to adjust our knowledge about this area. Definitely we have underestimated the number of inhabitants who lived here in the 13th century and the complexity of their religious practices, which must have also taken place next to these outdoor panels”.

Ongoing research at the site will proceed with a two-tiered approach, including collaboration with the University of Houston’s LiDAR team and local Ute tribe members to produce highly detailed digital maps and intimate historical records of the archaeological site. On the contributions of the Texan scientists, Palonka said he is excited at the prospect of developing “a detailed 3D map of the area with a resolution of 5cm-10cm”, a drastic improvement from current imaging.

With the additional help of Ute tribal archaeologist Rebecca Hammond, Palonka’s team will receive assistance in understanding and contextualising the works they discover. According to JU, conversations between Pueblo people and archaeologists will be integral to a forthcoming and permanent exhibit at the nearby Canyon of the Ancients Visitor Centre and Museum, where the Polish researchers’ latest findings will also be featured.

Meanwhile, Palonka’s team is eagerly awaiting the results of new mapping, he said, as they “hope to spot new, previously unknown, sites, mainly from earlier periods”.