At first sight it looks absolutely nothing like a Van Gogh: a portrait of a fisherman mending his net and smoking a pipe by the seashore. It lacks the strong colouration, thick impasto paint, energetic brushwork and style of the work of the Dutch artist in Provence. Yet the New York-based LMI Group claims that this portrait, titled Elimar, is by no other than Van Gogh. Press reports have valued it at over $15m.

But could this unsigned picture, lacking any links to Van Gogh, really be by the master? LMI has an answer: they argue it is the Dutchman’s version of a work by another artist—a portrait of the fisherman Niels Gaihede by the Danish painter Michael Ancher (1849-1927).

Michael Ancher’s Portrait of Niels Gaihede (1870s-80) and Elimar by another artist

LMI Group

LMI titles their painting Elimar, after the word inscribed on its lower-right corner. They say that this refers to the name of a young seafarer in an 1848 novel by Hans Christian Andersen, The Two Baronesses. This inscription is missing on Ancher’s original painting and is only on the LMI version.

Elimar first surfaced in 2016 “at a garage sale held at a residence in Minnetonka, Minnesota”. LMI say the price was “very nominal”, with press reports suggesting that it was less than $50. The picture was later bought by LMI in 2019 for an undisclosed sum.

Following five years of research, LMI argues that Elimar was painted in 1889, while Van Gogh was staying at the asylum outside Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. That autumn Van Gogh began a series of painted versions of black-and-white prints by other artists he admired. LMI claims that it was then that he made this work—his own interpretation of Ancher’s.

Scientific staff investigating Elimar

LMI Group

Could Elimar really be a Van Gogh?

Elimar has recently been subjected to a series of comprehensive tests by LMI. These confirmed that the painting’s pigments were in use in the late 19th century, although with one possible exception: the pigment geranium lake, used to create violet in the sky, was initially thought to have only been patented in France in 1905. However, further research suggested a likely patent in 1883, six years before the mooted date of Elimar.

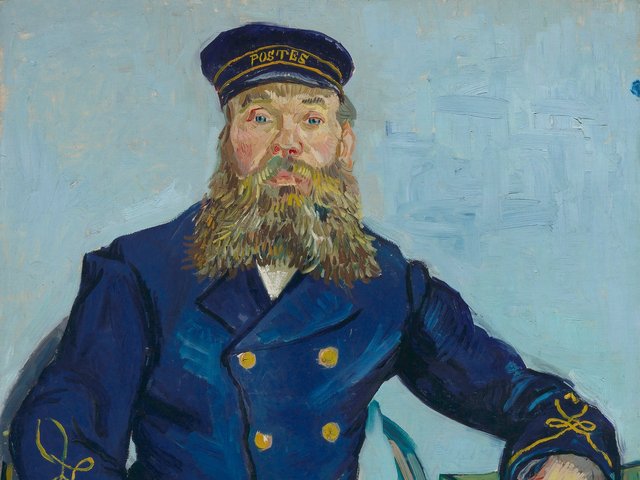

The investigations also revealed a hair embedded in the paint in the bottom-left corner. This was removed and tested for DNA, although the result proved “inconclusive” because of degradation of the sample. However, high-resolution images did suggest that the male hair was “translucent to red to light reddish brown”—Van Gogh is believed to have had reddish hair.

Enlarged image of a human hair discovered embedded in the paint of Elimar

LMI Group

LMI has gone to enormous efforts to argue their case, publishing a 458-page document which deals with the context of Elimar within Van Gogh’s life and work. Much of the report provides an extensive account of technical analyses, including pigments, a thread count of the canvas, the use of a palette knife, egg-white finishing, etc. A comparison of the capital letters “ELIMAR” on the LMI picture is said to reveal a “94 per cent similarity” with some of those on accepted Van Gogh paintings.

Although the American writer William Havlicek, author of Van Gogh’s Untold Journey (2010), accepts the painting’s authenticity and has written a preface to the lengthy LMI report, the document cites no internationally recognised and extensively published Van Gogh specialists who regard it as authentic. Most significantly, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the ultimate authority, does not accept it.

Normally the Van Gogh Museum does not comment on new “discoveries”, which emerge constantly (I hear of one candidate almost every week). Previously unknown paintings which are eventually accepted as genuine by the museum are extremely rare. They probably now turn up once every ten to twenty years.

However, the Van Gogh Museum did take the unusual step of speaking out on Elimar. On 31 January a spokesperson said: “We have considered the new information mentioned in the LMI's Elimar report. Based on our previous opinion on the painting in 2019, we maintain our view that this is not an authentic painting by Vincent van Gogh.”

In 2019 the museum responded to an authentication request from an earlier owner of Elimar, stating: “We have carefully examined the material you supplied to us and are of the opinion, based on stylistic features, that your work cannot be attributed to Vincent van Gogh.”

Delving Deeper

The museum itself is not commenting further on any details—but let’s look into the evidence. The painting only emerged in 2016 and there is no earlier provenance to link it to Van Gogh, or to explain how it travelled from the asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence to a garage sale in Minnesota.

Concerning the Elimar name, there is no specific evidence that Van Gogh ever read Andersen’s novel (although he enjoyed his writing), and in 1889 the book was not available in either Dutch or French. Van Gogh did also read English and German, and the book had already been translated into these languages, but he would not easily have seen a copy in Provence.

More significantly, it seems very unlikely that Van Gogh knew of the original Ancher painting on which Elimar is based, despite LMI’s speculation. The fact that the colours of Elimar are similar to those of Ancher’s Portrait of Niels Gaihede, surely means that the artist behind LMI's work must have had access to the original picture.

Nothing is known about the provenance of the Ancher picture before it was first auctioned in 1975, so it must have been in an unidentified private collection during Van Gogh’s time. It is inconceivable that the Ancher would have been at the asylum where Van Gogh lived, and the chance of him having seen the Danish painting in a private collection in Paris two years earlier and then remembering its composition and colouring seems very remote.

In 1889, at the asylum, Van Gogh was painting his own coloured interpretations of black-and-white prints by other artists, not copies of paintings by them. No prints of the Ancher are known, and even if Van Gogh had had one, it is extremely unlikely that by chance he would have reproduced the Danish artist’s colours from a black-and-white image.

But the latest challenge faced by LMI is the argument that the word “Elimar” does not represent the character from the Andersen novel, but is actually the signature of another Danish artist: Henning Elimar (1928-89). He is a minor figure and two of his landscapes were last week on sale for just over $150 each (with all the publicity over Elimar they very quickly sold).

A comparison between the handwriting on Elimar and Henning Elimar’s Village in Winter, which was auctioned by Dannenberg in Berlin last September, is telling. The word “ELIMAR” has been written in capital letters in a similar style, and in the same position, on the two paintings. However, LMI disputes the suggestion that they are written by the same hand, pointing out that Henning Elimar’s capital letters “have a distinct rightward tilt”.

Henning Elimar’s Village in Winter (mid-20th century), his signature (upper right) on Village in Winter, and the signature on LMI’s Elimar (lower right)

Although the LMI report includes a 35-page section analysing the handwriting of “Elimar” on their painting, this does not even consider the obvious possibility that it might represent the name of the artist. The lower-right corner of a painting is the most common place for an artist to sign and it would be curious to instead write the name of a sitter on their sleeve.

LMI sent us a detailed response, saying that Henning Elimar was “never considered as a potential author” of their painting, because of a lack of “any similarities in style, technique, subject matter, palette or epoch” with their own picture. Their statement adds that there is “no evidence of the work [Elimar] having been painted in the 20th century”, since it does not have certain modern pigments and binding media.

However, I would argue that the fact an artist used only materials available in the 1880s does not rule out the possibility that a work was painted in the mid-20th century.

Real or not: who decides?

LMI dismisses the Van Gogh Museum’s rejection on the grounds that it was not based on a physical examination of the painting, but simply on images and supporting written material. It also stresses, with reason, that attributions can change, as scholarship and science advances.

The company explains: “There have been at least four instances in which the Museum reversed its own prior opinion on the question of authentication of a Van Gogh work, and at least ten additional instances in which the Museum reversed the attribution of works previously included in catalogues of Van Gogh’s oeuvre [published in 1970 and 1996].”

I myself do not authenticate Van Gogh’s work, since I feel this is a task which should be undertaken by the Amsterdam museum, which is dedicated to the artist. But for me, the evidence linking Elimar to Van Gogh is unconvincing.

The future of Elimar remains unclear, although the emergence of the painting has certainly attracted global media attention. Within two days of the announcement, fridge magnets with the image were on sale on eBay for $9.