For more than six decades Liliane Lijn has been working at the interface of visual art, poetry, performance and science. Born in New York in 1939 and based in London since 1966, her multifaceted work spans sculpture, installation, collage, painting, video and performance. And she has never ceased to experiment and push the limits of her practice. Lijn was an early pioneer in the use of light, movement, and the latest in plastics and man-made materials, as well as observing—often at first hand—new discoveries at the Space Sciences Laboratory of the University of California, Berkeley, and at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (Cern) in Switzerland. At the same time, she has also been deeply influenced by ancient civilisations, mythology and Eastern philosophy.

Now, the full range of her work can be seen in Liliane Lijn: Arise Alive, a comprehensive retrospective on show at the Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien (Mumok) in Vienna, which travels to Tate St Ives in May. She is also participating in a couple of important group shows: Radical Software: Women, Art and Computing 1960-91 at the Mudam Museum of Modern Art in Luxembourg (until 2 February) and Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet at Tate Modern in London (until 1 June). Her memoir, Liliane Lijn: Liquid Reflection will be published by Hamish Hamilton, Penguin Random House on 13 March.

The Art Newspaper: From your earliest fantastical scroll drawings through to the kinetic and illuminated works using plastics, prisms, rotating text cylinders, cones and giant multimedia female figures, a sense of energy, movement and experimentation permeates your work. What drives this impetus?

Liliane Lijn: I’m a restless person. I started by painting, but then I realised that that was useless if you didn’t know how to draw. So I drew and drew and got deep into these scroll-like drawings that I called Sky Scrolls. But after a while I felt I was repeating myself. I tried doing them on raw canvas and that didn’t work, so I started thinking of other things.

Then, around 1960, I found this weird material which was actually a new kind of plastic wax for skis. It was a polymer and it came in lots of colours. I started playing with it and realised I could create very thin lines by injecting it onto perspex, which made shadows on the wall or any white surface. Then, when I moved around, I could see the whole work changing: moving and vibrating. I became fascinated by that. This is what started me working with plastics, light and motion. Working with light changed everything because my work then became very experimental. But all this was only about a year after I’d started making art in the first place.

Conjunction of Opposites: Woman of War and Lady of the Wild Things (1983–86)

Photo: Thierry Bal; © Bildrecht, Wien 2024; courtesy of Liliane Lijn and Sylvia Kouvali, London/Piraeus

You did not go to art school and instead your gateway to becoming an artist was when you travelled to Paris at the end of 1958 with a friend whose mother knew André Breton. There, you met the Surrealists and took part in their meetings. How important was that time?

I didn’t go to their café meetings for very long; it was the end of Surrealism and they weren’t that interesting. I was only 18 when I went to Paris and everyone I knew was 20 or 30 years older than me, apart from one or two girlfriends. Although I met Toyen and Méret Oppenheim, it was a very male world. And Breton wasn’t really all that nice. But that first year in Paris was such an intense time when so much happened and most of the significant influences on my work were put in place. I found the breadth of Surrealism and the fact that they were equally interested in science and in archaeology, in art and poetry, deeply inspiring. I studied archaeology and art history at the Sorbonne and the École de Louvre for about six months but then I decided the most important thing was to focus on drawing and learning.

Through more than six decades making art, you have always cited writing and language as a crucial cornerstone to your creativity.

From year zero I wanted to write, and through the whole of my practice, right from the beginning up until today, I’ve always incorporated language and used words in my work.

When I made the Poem Machines in the 60s, I was reading quite a bit of science and at the same time I was looking at scientific experiments with light; I was also trying to see the vibrations and the energy of sound. In these works, the words became unreadable as the shapes turn and vibrate, and what interested me was the relationship between the oral and the visual word, and how to connect them. Words are energy, and we transmit this energy from one person to another when we speak. And then I started collaborating with poets and using their words, as well as my own.

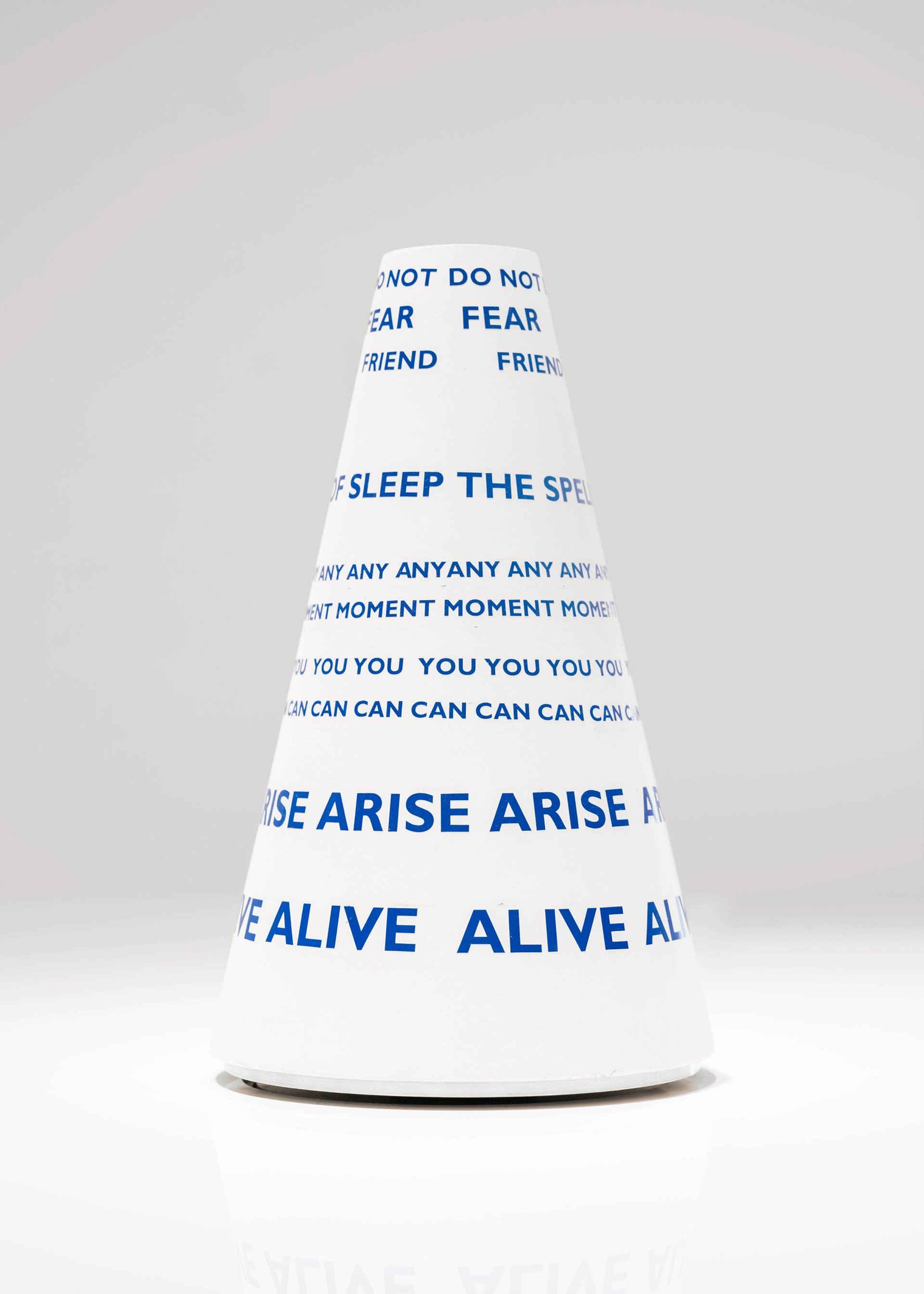

Lijn's Arise Alive (1965) Photo: Maximilian Geuter; München; Haus der Kunst München; © Bildrecht; Wien 2024

Although your work comes in myriad shapes and substances, you are especially known for your cones, which you call “koans” after the paradoxical, unsolvable riddles of Zen Buddhism. Why do you keep returning to this form?

The cone is so complex; there are so many areas in which it is important and I keep discovering more. Planetary motions are all elliptical, like parts of the cone. The geometry of the cone is very complicated, or so I’m told by mathematicians looking at my cones. Many cultures take the cone as a symbol of the mountain, reaching up towards the sky. But I always think of the mountain as firmly based on the ground. I’ve heard the most extraordinary things about the cone, but it always comes down to the feminine for me. For the Greeks, the conical mound of ash was given the name of the female goddess, Hestia, who presided over the hearth. It’s also the basic form of the skirt, and especially the ancient Sumerian skirt that looks very much like a cone; even though both men and women wore it, in the end it’s the female symbol. And then, of course, it’s the shape of the breast.

How does this deep interest in ancient civilisations, archetypes and mythologies sit alongside your use of radical materials and your numerous residencies at the most world-renowned centres of cutting-edge scientific research?

I believe they’re all connected. When I went to Cern and heard their ideas about cosmology, I realised it was just another creation myth: today our creation myth is based in science. I think that we have our own mythology and in science these mythologies continue to be incredibly powerful: so much of the terminology alone comes from ancient Greece. They’re always looking back, looking forward. There isn’t a separation between the past and the future.

Your work has been described as “technological feminism”. Do you see your embracing of so many science-based methods and materials as expressions of female empowerment?

I felt—and feel—that women have been disempowered, physically, spiritually and mentally. There are many examples of extraordinary, brilliant women who have not been recognised in the arts. But there are so many more in science, because women weren’t considered able to be physicists, engineers or mathematicians. Yet when they used women during the Second World War in America, they were doing all the calculations faster than the machines and they never got any credit; it was disgusting. I think women have had a hugely bad deal when it comes to their brains, their spirit and their imaginative world.

The Bride (1988) is in Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet at Tate Modern. Made of mica with a flashing head, Lijn advises: “you don’t want to go into that cage because it’s charged with 500 volts” Photo: Lucy Green, © Tate

Some of this anger seems to break out in the giant female figures of your Cosmic Dramas series, whether Woman of War (1986) and Electric Bride (1989), on show at Mumok, or The Bride (1988) in Electric Dreams at Tate Modern. These scary cyborg goddesses made from both natural and manmade materials, and often using light and sound, mark a different expression of the feminine from your Koans.

I wrote a book called Crossing Map, which started out as science fiction but by the time it was eventually published, in 1983, it had become more of an ecological feminist manifesto. After I wrote it, I felt that I wanted to discover a new feminine form, to visualise the feminine inside me in all her aspects and potentials. There are two sides to the feminine archetype: at best she can be luminous and creative but, after 5,000 years of repression, she can also be very dark. If you go to a power station and in the chimneys or the reactors you see these figures, they’re standing there, just like the ancient female goddesses with their hands up. According to Jung, repressed archetypes do not die; they become more powerful. I don’t see why the feminine has to be confined to clothing and sewing machines: the idea that the technological and the industrial is not feminine is insane.

There is certainly a threatening feel to these flashing, looming female figures of the 1980s.

From the beginning of the 80s I started becoming more articulate about feminism and trying to make a difference as a woman artist. Woman of War has computer-controlled movements and is the embodiment of a song that just came out of my subconscious one day in Paris. She’s a great female archetype, a warrior woman who is warning humanity that they are destroying their planet. The Bride in Tate Modern’s Electric Dreams is more subdued. She’s in a cage and I’m using natural material: she’s made of mica stone, she’s like geology and looks like the side of a cliff. But she has a flashing strobe head and you don’t want to go into that cage because it’s charged with 500 volts.

The damage to the planet that you recognised in the early 80s continues apace and the misuse of technology also shows no sign of stopping. Do you still feel that art can change people’s perceptions and the way that we view the world?

I don’t know if we can change things, but I think we can certainly give people some courage. To really change things, we’ve got to vote in governments that will make the changes; we can’t do it ourselves. Art can protest, but I’m not the protest type. I feel that it’s more important to give people hope, to make them feel—at least for a while—some kind of light, some kind of illumination. I think it’s important that people do not despair, because you won’t do anything positive if you’re just depressed.

• Liliane Lijn: Arise Alive, Mumok, Vienna, until 4 May; Tate St Ives, 24 May-5 October