The German Expressionist artist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938) was a physical and psychological wreck when he first arrived in Davos in 1917. Addicted to alcohol and morphine, he was suffering from blackouts and paralysis. His First World War service had lasted just a few months – in September 1915, he was discharged because of mental illness and spent most of 1916 in sanatoriums in Berlin.

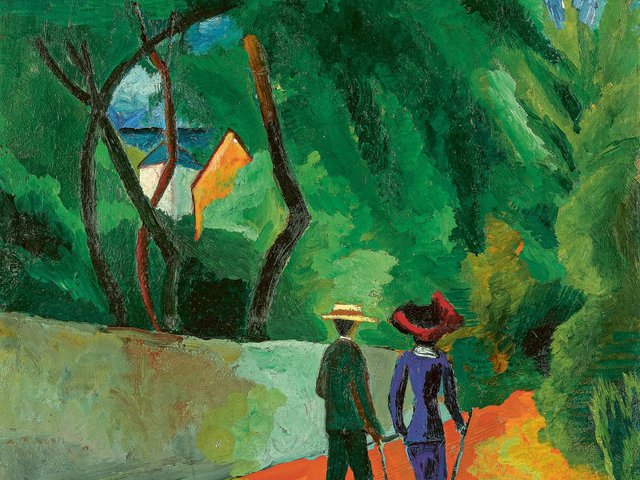

By then Kirchner had already earned wide recognition in Germany. Together with Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Fritz Bleyl he had founded the Brücke group of artists in Dresden in 1905. Their revolutionary manifesto was to “call on all youth to unite, and as the standard-bearers of the future, assert our creative freedom and freedom of lifestyle in a stand against comfortably entrenched older forces.” The Brücke paintings of the era reflect their bohemian lifestyle, often portraying young female models skinny-dipping in the lakes around Dresden.

In 1911 the group moved to Berlin, where Kirchner produced the erotically charged street scenes he is still best known for—angular figures, often prostitutes and their customers, painted in strident colours against the backdrop of the pulsating metropolis that so inspired him. But as the First World War loomed, his despair increased, and so did his dependence on absinthe.

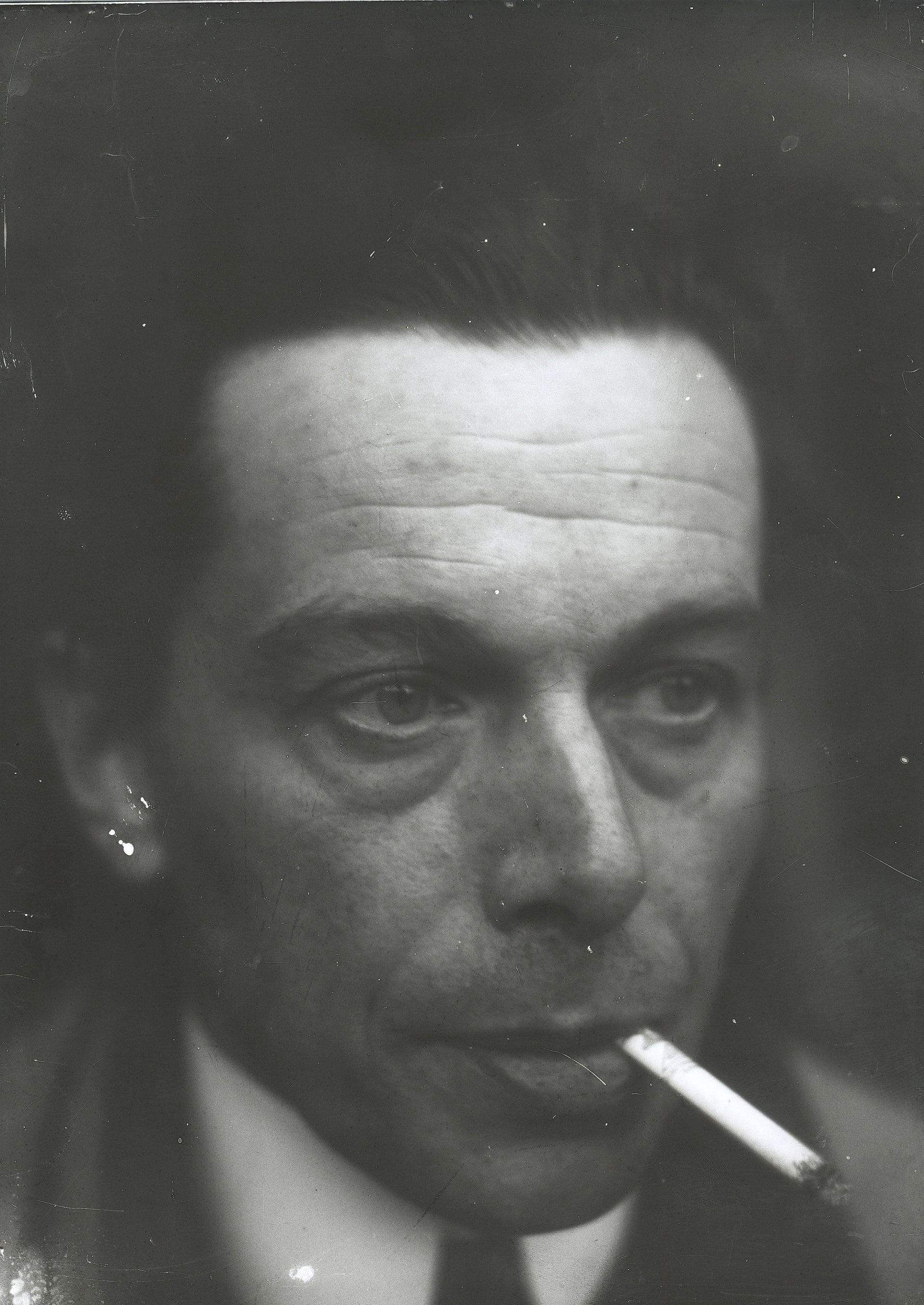

Kirchner in an undated self-portrait Courtesy of Kirchner Museum Davos

Kirchner’s first visit to Davos was for just a few weeks. But he would later make it his long-term home, and stayed there until taking his own life in 1938.

His later work is now gaining increased recognition, both on the art market and in museum shows. Some of the vibrant mountain landscapes he painted in Switzerland—as well as earlier works—are on view at the Kirchner Museum Davos, founded and owned by the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Foundation. The museum is closed to the public during the World Economic Forum, when it hosts private functions connected to the event. From 9 February to 4 May 2025, it is showing an exhibition focused on the frames Kirchner made (and often painted) for his works.

The artist’s homes in the Alpine spa town and ski resort are still standing: here’s a tour through Kirchner’s Davos.

A photograph of Davos Stafelalp Courtesy of Kirchner Museum Davos

Stafelalp

On his second visit to Davos in May 1917, Kirchner arrives in precarious health, accompanied by a nurse. They live on the Stafelalp in a mountain hut (above and, depicted in Stafelalp im Schnee at top). “It’s very beautiful up here ... and I could paint so much, if I weren’t so weak,” he wrote. At the end of August, Kirchner’s friend, the Belgian artist Henry van de Velde, visits and advises Kirchner to move to a sanatorium by Lake Constance. During this crisis period, Kirchner focuses mainly on prints and drawings.

Kirchner made furniture for his house In den Lärchen in Davos, including this Bett für Erna Schilling (1919) Courtesy of Kirchner Museum Davos

In den Lärchen

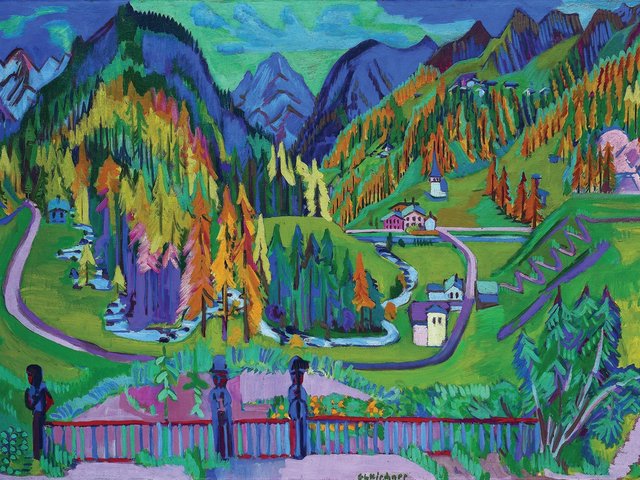

Kirchner returns to Davos in July 1918, and in September, moves into a house in a courtyard called In den Lärchen. He paints vibrant, tapestry-like, panoramic Alpine landscapes and creates furniture and sculptures for his house.

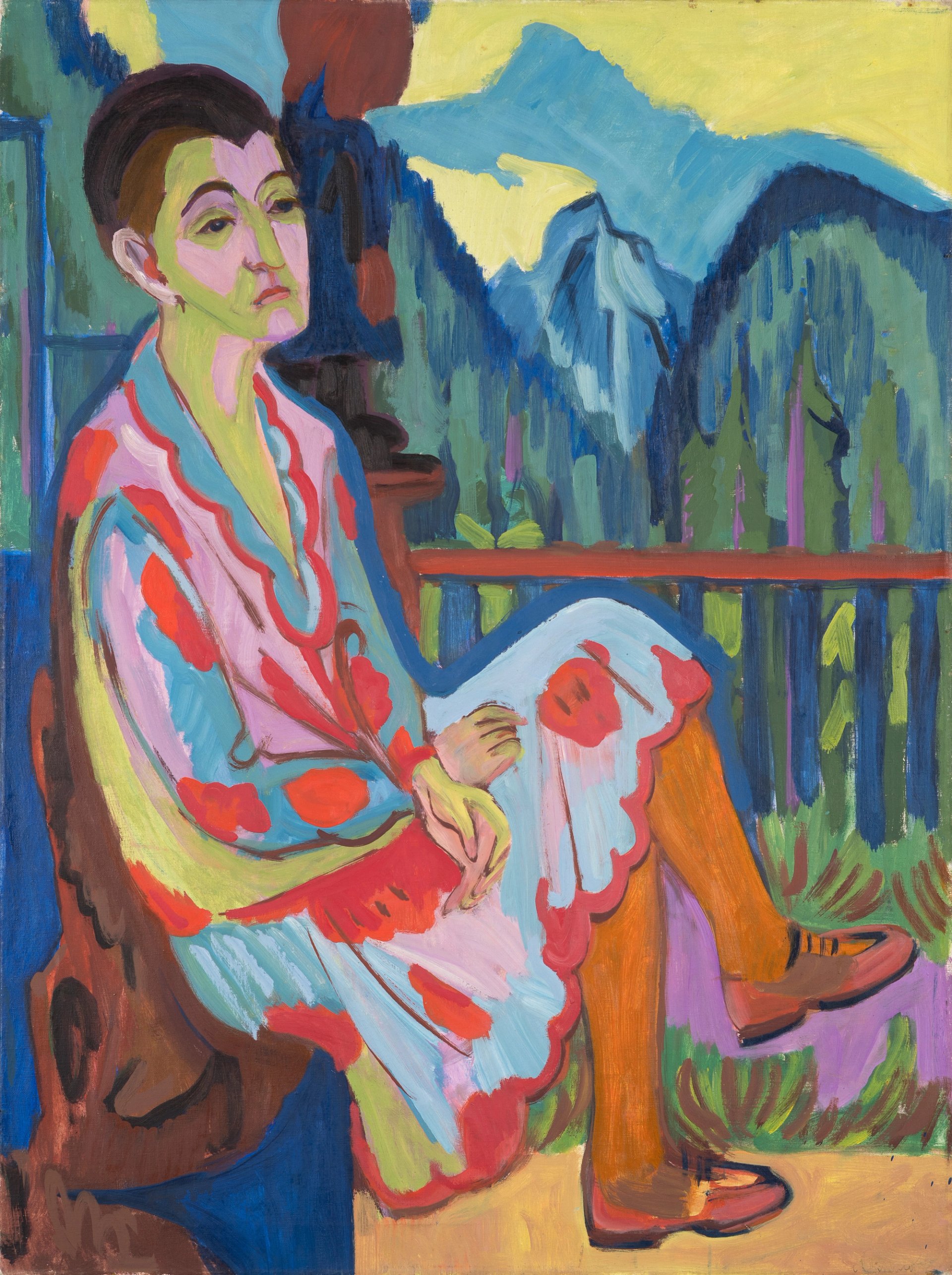

Sitzende Dame (1926) by Kirchner is a portrait of his partner Erna Schilling Photo: Stephan Bösch; courtesy of Kirchner Museum Davos/Stephan Bösch

Erna moves to Davos

Kirchner’s partner of nine years, Erna Schilling, moves permanently to Davos in 1921. Fifty of his works are shown in the Kronprinzenpalais in Berlin that year. In 1922, Kirchner meets Frédéric Bauer, a doctor in a Davos clinic, who becomes one of his most important collectors and patrons.

Wildboden, the artist’s third and last home in Davos Courtesy of Kirchner Museum Davos

Haus auf dem Wildboden

After falling out with his landlord, Kirchner rents a new house in 1923, Haus auf dem Wildboden. In June, he has a solo exhibition at the Kunsthalle Basel. But he struggles to gain recognition in Switzerland, because “people are used to French artists and are shocked at my forms and colours,” he wrote. “People are fighting against my art of today just as they did ten years ago against my art of that time, which is now valued.” In 1925, he paints his last major panorama of the Davos landscape, Sertigtal im Herbst. He mounts an exhibition, Kirchner 10 Years in Davos in 1927; Kirchner shows are also held in Wiesbaden, Dresden and Zurich. During the 1920s, he receives dozens of guests: he ritually photographs visitors by the window in Haus auf dem Wildboden.

During his years in Davos, Kirchner was a regular at Café Schneider where he sketched the customers for paintings including Café am Morgen (1935) Courtesy of Kirchner Museum Davos

Café Schneider

Kirchner frequents Café Schneider and sketches its customers regularly during his years in Davos. From the mid-1920s, he develops what he called his “new style”, seeking to “recreate the inner image with abstract forms”. His most important project in the late 1920s is planning a series of frescoes for the banqueting hall of the Museum Folkwang in Essen; he also turns his attention to painting nudes in nature.

Rise of the Nazis

Kirchner remains heavily reliant on a German market that looks increasingly precarious in the early 1930s. In 1934, a year after the Nazis seize power, the director of the Folkwang is fired and Kirchner’s frescoes are never realised. From 1936, Kirchner starts taking morphine again for bowel pains. In 1937, his works in German museums are seized as “degenerate art”. A friend reported that Kirchner destroyed sculptures and drawings and used some of his best paintings as target practice. On 15 June 1938, three days after withdrawing his marriage proposal to Schilling, he shoots himself (although recently his suicide has been disputed). He is buried near his home at the Waldfriedhof cemetery in Davos.