“Suicide without a doubt” was the verdict, in a Swiss medical report dated 16 June 1938, on Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s death by two gunshots to the chest. But more than 80 years after his death, a number of weapons experts say it is very unlikely he fired the gun twice himself.

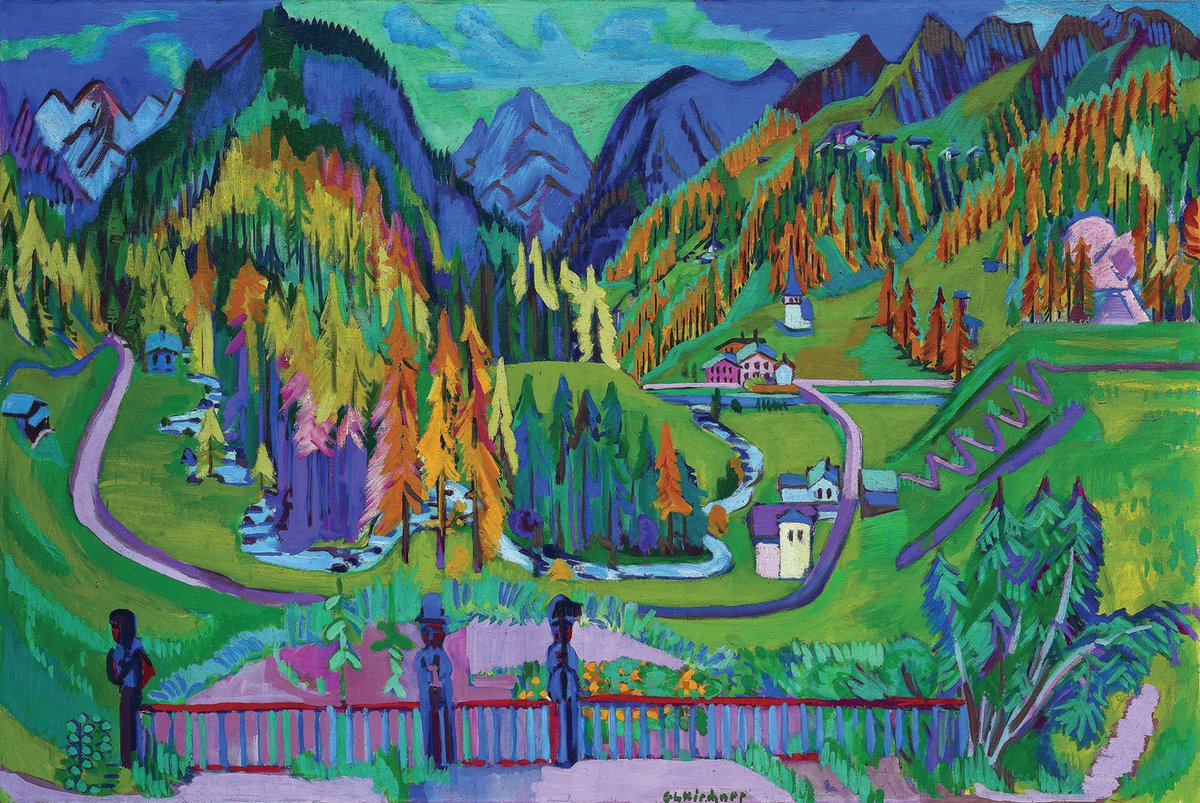

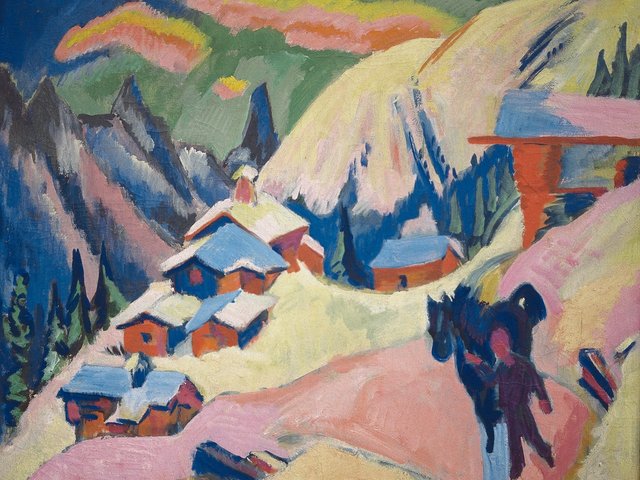

Kirchner’s pistol, an FN Browning Nr. 96151 made in Belgium, was on show at an exhibition at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, Europe on Cure: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Thomas Mann and the Myth of Davos until 3 October. Kirchner fled to the mountain resort of Davos in 1917 to escape the First World War and emigrated there in 1918 to make a fresh start.

The gun is fitted with a safety device that means it can only be fired with a firmly squeezed hand. Given the weapon’s recoil from the first shot and the injury the bullet would have caused, it is doubtful that Kirchner could have fired it a second time, says Andreas Hartl, an expert in guns.

Contradictory evidence

While it is possible Kirchner shot himself once, “it is more usual for people committing suicide to shoot themselves in the head”, Hartl says. Given the safety catch on the Browning, “you would have to hold the gun very strangely to aim at your chest”.

Hartl also says that at such close range, the release of gas would have burned skin and clothing. But the medical report—which contains other contradictions—described just two small holes between Kirchner’s ribs. That would suggest someone shot him from a distance, Hartl says.

The medical report also stated that two witnesses heard a shot (not two shots) and saw Kirchner fall to the ground. It concluded that Kirchner’s “inner turmoil brought him to despair”.

Kirchner, one of the founders of the Expressionist group Die Brücke (1905-1913), was without doubt in bad mental shape. The simple, ordered life the artist yearned to find in Switzerland eluded him. He had arrived sick and emaciated and dependent on drugs and alcohol.

By 1932, he had again resorted to drugs—this time Eudokal, a morphine derivative prescribed by his doctor. The rise of the Nazis in his home country probably contributed to the depression and sleep disorders that plagued him: 32 of his works featured in the Degenerate Art exhibition of 1937, with which the Nazis sought to ridicule and vilify modern artists. He was also ousted from the Berlin academy of artists.

A life derailed

His drug addiction got worse and in May 1938, he was again struck by depression. A friend reported that he had destroyed sculptures and drawings and used some of his best paintings as target practice. On 12 June, he withdrew his marriage proposal to Erna Schilling, who had moved from Berlin to Davos to live with him. He died on 15 June.

The Germanisches Nationalmuseum catalogue points out the discrepancies in the medical report and modern experts’ doubts about the official version of events. But his state of mind was without question suicidal, the catalogue says.

“His life had completely derailed: depression, sickness, thoughts of death, and attempts at drug withdrawal and the completely surprising decision to take back his marriage proposal were all clear warning signs,” it says. Who the potential murderer could have been remains a mystery.