Hundreds gathered in the Israeli city of Umm el-Fahem on a Saturday in mid-November, to unceremoniously mark the opening of six exhibitions. Normally—unlike now, as conflict rages in Gaza, Israel, Lebanon and Syria—this would have been a festive moment. The Umm el-Fahem Art Gallery was opening its first new exhibitions since receiving recognition as Israel’s first official museum of Arab culture, a significant step—and funding of 22m shekels (around $6.1m) from the culture ministry. The atmosphere, however, was subdued.

Established in 1996 as a private gallery by the local resident Said Abu Shakra and his brother, Farid, the Umm el-Fahem Art Gallery exhibits work by Palestinian, Arab and Jewish Israeli artists, offers art classes, hosts a residency programme and explores the Palestinian historical narrative. Its permanent collection contains more than 2,000 works and an oral history archive of around 600 videos of Umm al-Fahem and Wadi Ara residents recounting life before the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948. A breakout moment for the gallery was in 1999 when Yoko Ono held an exhibition there, but the breakthrough that Abu Shakra has long dreamt of is that of official museum status.

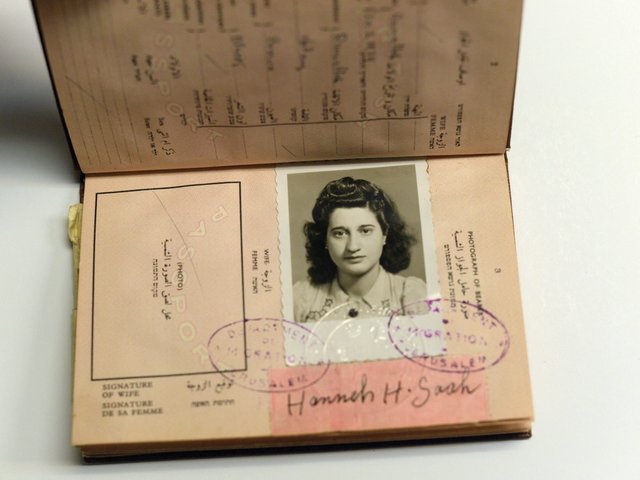

Umm el-Fahem Art Gallery’s first exhibitions since being recognised as Israel’s official museum of Arab culture includes Sobhija Hasan Qais’s solo show The Last Supper Courtesy of Umm el-Fahem Art Gallery

“I founded the museum in order to facilitate the display, documentation and preservation of Palestinian and Arab culture within the state of Israel, in the right way. But also to allow this culture, which I represent and display, to be a multicultural meeting place within Israel,” Abu Shakra tells The Art Newspaper. “To be curious about each other, to be interested in the culture of the other.”

Abu Shakra felt compelled to open a gallery after his cousin, the artist Asim Abu Shakra, died in 1990. The Abu Shakras are a respected family of artists from Umm el-Fahem, Israel’s third-largest Arab city. The brothers Said, Farid and Walid, their cousin Asim and Asim’s nephew, Karim, were the subject of a 2022-23 retrospective that attracted record crowds at the nearby Mishkan Museum of Art in Kibbutz Ein Harod titled Spirit of Man, Spirit of Place. Abu Shakra’s most ambitious creative project, however, is his gallery-turned-state-sponsored museum.

The gallery obtained national recognition by the former Naftali Bennet-Yair Lapid government under the Decision 550 programme. This five-year plan allocated 30bn shekels (around $8.4bn) to strengthen Arab community life, including 360m shekels (around $100m) earmarked for cultural projects including a theatre, acting school and cinematheque.

The culture ministry announced a call for proposals, and among others, selected the Umm el-Fahem Gallery with an official announcement in July 2024. The Knesset Appropriations Committee then approved the allocation of 22m shekels (around $6.1m) spread over five years, intended to transition the gallery to national museum standards.

Abu Shakra had already begun adopting museum standards by establishing a permanent collection, but this money will help it pay for a chief curator and administrator; establish purchasing, steering and operating committees; improve storage conditions for the collection; and upgrade the gallery’s database. The gallery is also relocating in a few months, giving it more space although certain exhibitions will remain a permanent fixture. A rotating display of work by the landscape painter and printmaker Walid Abu Shakra will always be on view. “Walid is a native of Umm el-Fahem and a source of inspiration for many Palestinian artists,” Abu Shakra says.

Walid Abu Shakra’s engraved landscapes of Umm el-Fahem and its surroundings is one of the six exhibitions that opened in November. Nearby are painted explorations of personal history and the complexity of Arab Jewish identity in Back to the Levant by Shy Abady. “Abady talks about himself as a person who is Jewish and also Arab,” Abu Shakra says. “It’s very important to hear him speak about that in order to understand how we’re actually not that different from each other.” On the same floor is an exhibition of recent paintings by the Palestinian artist Sobhiya Hasan Qais that confront the humanitarian crisis and starvation in Gaza.

Landscapes, textiles and video art

The first floor displays Fragments of Artificial Future by the Haifa-based artist Hamody Gannam, a graphic account of an imagined dystopian journey undertaken by a humanoid Palestinian robot named Saif. Nearby are landscapes by Ruth Kestenbaum Ben-Dov, painted near her studio, in a show titled Land of Painting. On the second floor are a travelling exhibition of video works created between the Yom Kippur War and the present conflict, and a show that pairs the fabric-themed works of the Israeli Jewish artist Caron Tabb and the local artist Nahawand Jbaren, who jointly created a video work at Khubbayza, a Palestinian village where Jbaren’s ancestors had lived and that was destroyed in 1948.

“We wove the first strands of a dialogue. I felt that through weaving a dialogue, we could share our humanity, break down barriers and reinforce what we shared in common through art,” Tabb writes in the trilingual exhibition catalogue (a routine practice at the gallery, with texts in Arabic, Hebrew and English). Jbaren adds: “The joint message from Caron and myself is a call for unity, solidarity and peace.”

Some of us have feelings of wanting revenge, and hate. This is where art can come in, to rehabilitate these feelingsSaid Abu Shakra

Recounting the Saturday when these exhibitions opened, Abu Shakra says that for the “hundreds of people who came to the exhibitions, both Jewish and Arab, it improved their emotional state and did them good. They said, this is how we want to live in this country, one alongside the other, one together with the other.”

It is not always easy to keep going, he admits, and he has also felt personally crushed by this war. “Some of us have feelings of wanting revenge, and hate. This is where art can come in, to rehabilitate these feelings. To show that we can do things differently. Art is a meeting place, a place of dialogue.”