Amid escalating violence between Palestinians and Israelis in Gaza in May, experts declared that the possibility of peace has never been more distant. As Israel marked its 70th anniversary and the new US embassy in contested Jerusalem was unveiled, at least 60 Palestinian protesters were killed at the border by Israeli troops. Despite the political tumult, a major Palestinian cultural foundation is preparing to open its new headquarters to the public on 28 June in Ramallah, in the occupied West Bank.

The A.M. Qattan Foundation (AMQF) was established in London by the late Palestinian philanthropist Abdel Mohsin Al-Qattan in 1993 and is a registered UK charity. It is now chaired by his son, Omar Al-Qattan, the former chairman of the privately-funded Palestinian Museum, which opened in May 2016 in nearby Birzeit. The AMQF runs the Mosaic Rooms, the ten-year-old space for contemporary Arab culture in west London, and has cultural and educational programmes in Gaza, the West Bank and Beirut.

“We had a big debate about having a permanent space,” says Al-Qattan, who favoured a decentralised network of satellite offices linked digitally, reflecting the geographically “fragmented” Palestinian community. “My father said that we needed a landmark—something for people to refer to, almost as a symbol,” he says.

Construction constraints

Building a world-class cultural institution anywhere is complex, but in the Palestinian territories, it is harder still. The $24m Palestinian Museum opened after years of delays and lay empty of exhibits for 15 months. Construction on the AMQF building began in 2012 and was scheduled for completion in 2016, but the constraints of working in the region have caused a series of setbacks.

“The local construction industry is not used to this level of complexity and detail,” Al-Qattan says. An inexperienced contractor underestimated the costs of realising the project designed by the Spanish firm Donaire Arquitectos, now estimated at $15m to $18m overall. It was difficult to transport materials across the Israeli border and to find skilled workers, as many are tempted by the higher salaries in Israel.

“There’s a vulnerability about us that might scare some owners of collections”

At 7,700 sq. m, the venue has more than double the space of the Palestinian Museum, and will house art studios, exhibition spaces, classrooms, a library, a small theatre and a restaurant, as well as offices. However, the foundation has cut back its opening programming because of the delays, and staff are unlikely to move in until after the summer.

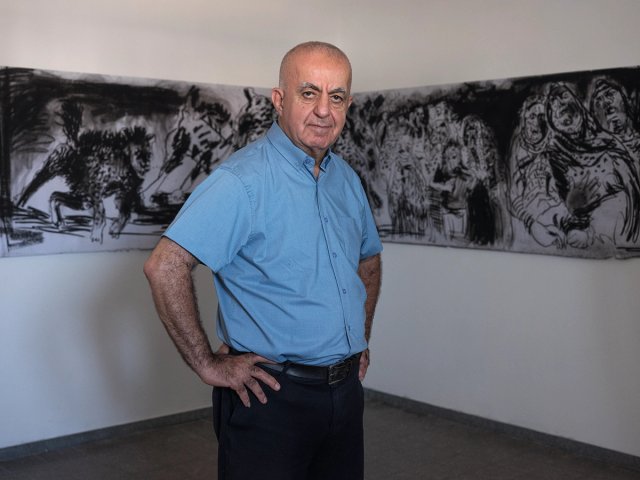

“The biggest challenge, apart from money and obviously the Israeli occupation, is human resources,” Al-Qattan says. “It is virtually impossible to get a work permit for somebody who doesn’t have Palestinian or Israeli identification.” This limits the pool of candidates at all levels—from curatorial assistants to directors—as few people in the area have the relevant experience, particularly on a large scale. The Palestinian Museum is already searching for its third director. The AMQF now has more than 100 staff, with 60 based in Ramallah.

The A.M. Qattan Foundation in Ramallah Photo: Ahed Izhiman. Courtesy A.M. Qattan Foundation, March 2018

Barriers to movement

Moving art in and out of the area is another hurdle. The foundation will host free exhibitions, starting with Subcontracted Nations (28 June-29 September), a group show of more than 60 artists and collectives, including Khaled Jarrar, Larissa Sansour and Naeem Mohaiemen, which questions the concept of the nation state. “Most of the pieces were either commissioned or are copies due to the complicated security measures on shipping to Palestine through Israel,” says Yazid Anani, the show’s curator and the foundation’s director of public programming. In October, the AMQF will participate in the Palestinian biennial Qalandiya International.

The foundation has not yet decided whether its own collection will go on show in Ramallah. “We function in an environment where you have to be very careful about owning something that is easily destroyed or stolen,” Al-Qattan says. The insecurity also makes it difficult to borrow works. “There’s a vulnerability about us that might scare some owners of collections or other museums. We will see.”

The key to working within the complex Palestinian political structures is autonomous funding, he says. “It gives you the freedom to function as the board sees fit.” The Al-Qattan family provides at least 60% of the foundation’s funds and an endowment has been set up for the building. “This doesn’t mean there won’t be attempts to interfere,” Al-Qattan adds. “The way it tends to happen is through added bureaucracy or investigations. We have never had this but I can see the possibility of it happening.”

Collaboration and rivalry

The foundation has weathered two decades of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, organising its first Young Artist of the Year Award exhibition in Ramallah as the second Palestinian uprising erupted in 2000, and the second under curfew. So while current tensions could derail the planned inauguration at the end of the month, Al-Qattan is already looking ahead, to the foundation’s future collaboration and rivalry with the Palestinian Museum. “Competition is good, it widens ambition,” he says.

Art against Islamophobia

Lara Baladi Al Fanous el Sehry’s The Magic Lantern (2002) at the Townhouse Gallery Courtesy of the artist

When the Mosaic Rooms—the London branch of the A.M. Qattan Foundation—opened in 2008, its chairman, Omar Al-Qattan, knew he wanted to use the space to counter growing Islamophobia in the UK by showing the rich cultural side of the Arab world. Over the past decade, it has become a leading exhibitions venue for emerging Arab artists and established figures from the region who are less well known internationally.

The tenth anniversary programme, which began in March, expands to Iran for the first time and has a stronger focus on Modern art. The space is presenting six exhibitions over 18 months; three solo shows of Modern artists—Bahman Mohassess from Iran, Mohammed Melehi from Morocco, and Egypt’s Hamed Abdalla, currently on view (Arabécédaire, until 23 June)—will mirror three thematic group exhibitions of contemporary artists from the same countries.

The first group show is a retrospective of Cairo’s Townhouse gallery, one of the few independent art spaces in Egypt (What Do You Mean, Here We Are?, 6 July-15 September). The show aims to “speak candidly about the challenges faced by independent institutions operating under censorship,” according to a press statement.