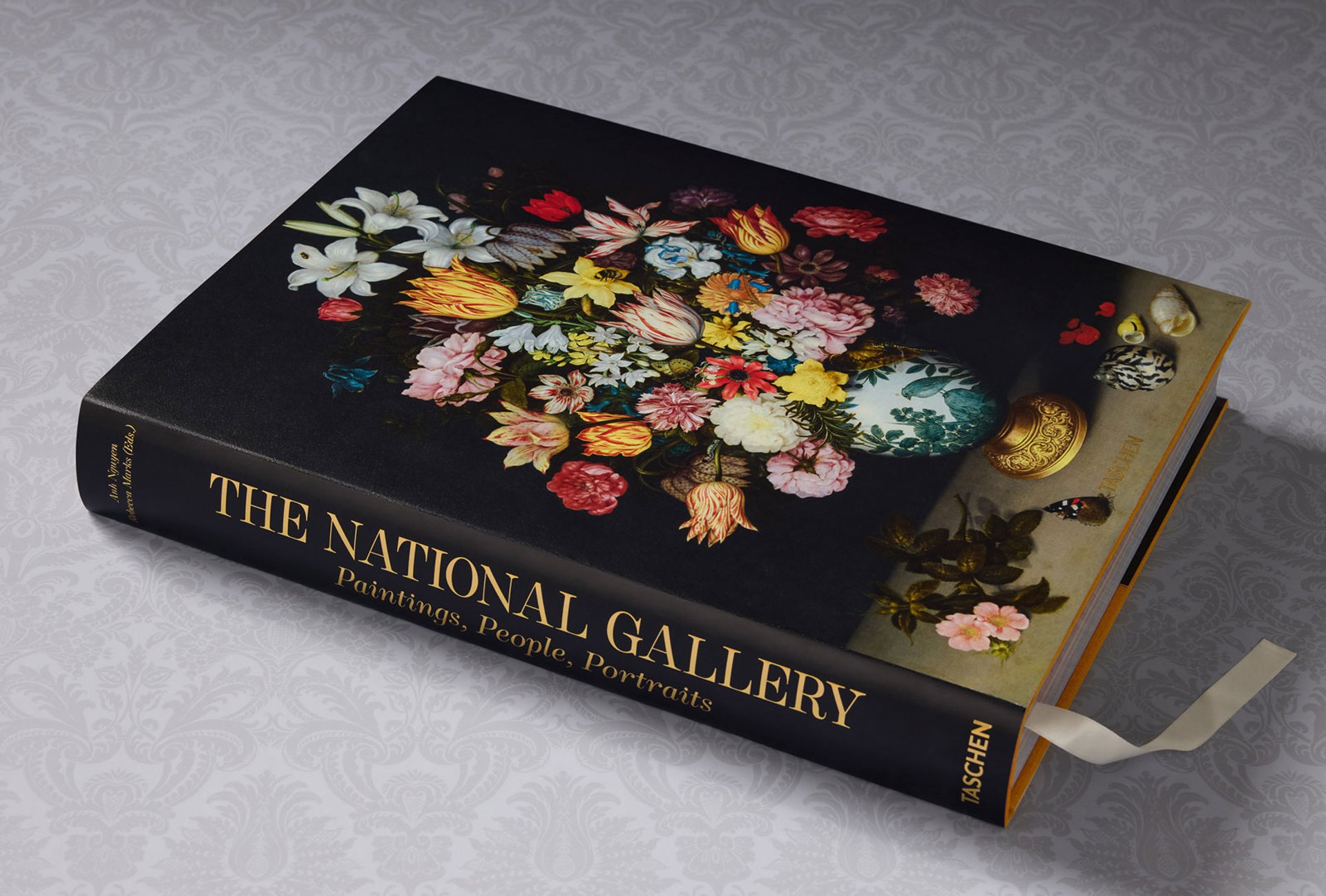

A hefty tome about the National Gallery in London comes hot on the heels of the museum’s 200th anniversary celebrations. The National Gallery: Paintings, People, Portraits, published this month by Taschen, includes a history of the institution and takes readers through key periods in art.

One of the highlights is a section devoted to favourite works in the collection, selected by celebrities, creatives, curators and artists. Among those talking about their preferred National Gallery painting are Frank Auerbach, Flora Yukhnovich and Rachel Whiteread.

Notably, Piero della Francesca’s The Baptism of Christ (1437-45) has been selected by three artists. David Hockney calls it a “truly a magnificent picture”, while Antony Gormley says its stillness suggests “another world free from pain and uncertainty”. In the extract below, the Venezuela-born, London-based artist Alvaro Barrington tells us why he thinks the painting is so special.

Extract from The National Gallery: Paintings, People, Portraits

Sometime around 2010, a shift was beginning to happen for young American painters. The artist Philip Guston began to be more relevant for our generation than his close high-school friend, the painter Jackson Pollock. It was a moment when, at least in the north-eastern corners of America, more and more artists were becoming increasingly explicit about how art and politics, chosen and not-chosen identities, were informing what they painted. For me, a kid who grew up in hip-hop with rappers like Tupac and Biggie and Lil’ Kim, the subject of Guston’s paintings felt quite in keeping with what I understood was in the domain of art, so he immediately became a guiding light. When the time came to choose where to study, I read Guston’s essay Piero della Francesca: The Impossibility of Painting (1965). I also found out that once, after opening a show, he came to London to look at Piero della Francesca and Uccello. If I could understand Piero, I could understand painting.

Painting, as [with] all art forms, works within a logic of its own potential. Another way of putting it, is a phrase I frequently heard in art school: “there needs to be meaning in the making”. The effect of a painting on someone is embedded in its making. In The Baptism of Christ, the most written about possibility is the stillness that Piero achieved. By contrast, think of Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942-43), and the impossibility of the eye to stay still when looking at it. There is a balance in The Baptism of Christ that allows one’s eyes and body to rest, to stay still, while at the same time one’s eyes move without struggle across the painting. Stillness is a common concept in Christianity, and here was Piero making meaning in the making in the most brilliant way possible. There is a straight line right down the middle, from the dove to the water being poured over Christ’s head to his hands palmed together. The lean in his leg and John the Baptist’s, the curve of the water, the openness of the sky weighed against the cramped angels under the trees, the figure in the background whose arched back follows the roundness of the frame—it all forms an impossible stillness that many contemporary artists, including me, have chased in their own paintings.

• The National Gallery: Paintings, People, Portraits, Taschen, 582pp, £175 (hb)