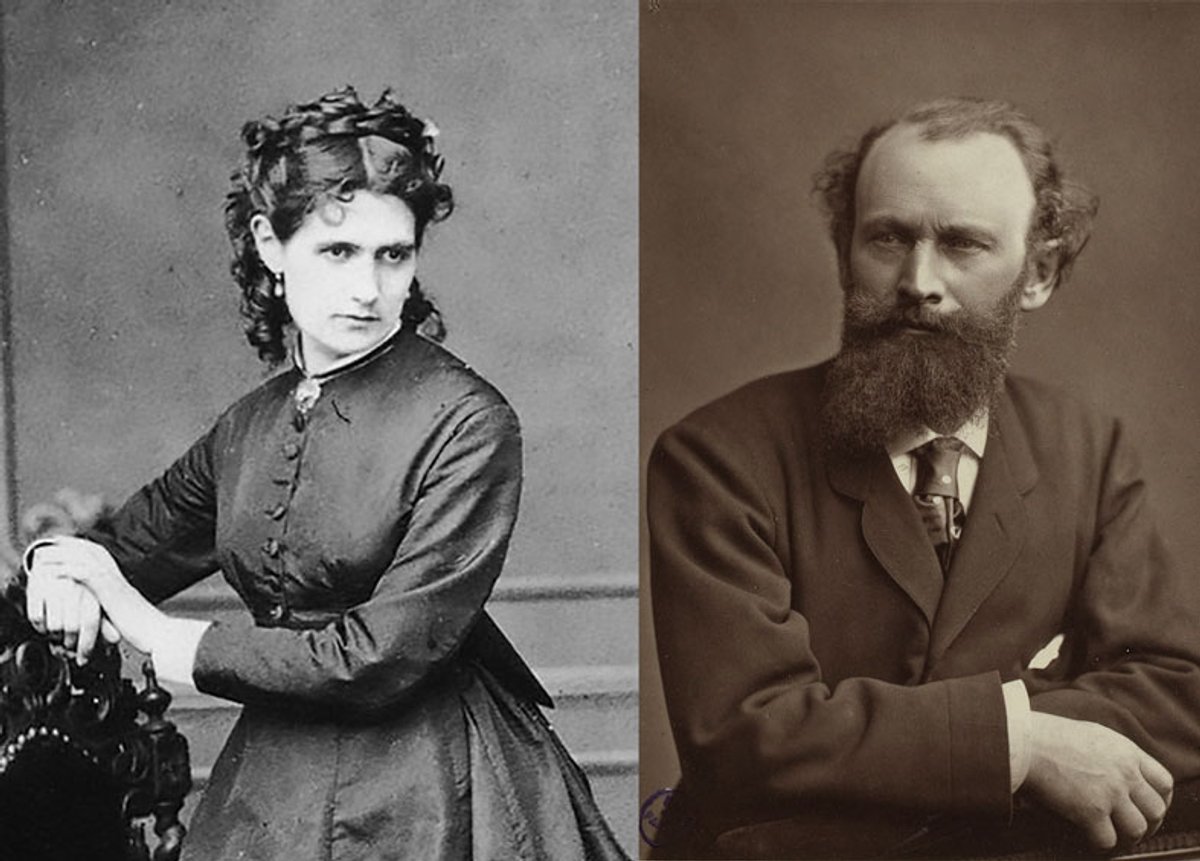

A new book by Sebastian Smee, the Washington Post art critic and former contributor to The Art Newspaper, tells the story of the Siege of Paris and the subsequent Commune through the eyes of the Impressionist artists who were there, such as Édouard Manet and Berthe Morisot.

As well as covering the upheaval and the violence of the bitter winter of 1870 and beyond, Smee also details some more humorous moments. In this extract from the book, Morisot has been working on a double portrait of her sister and mother—which she wanted to submit to the Salon of 1870—before Manet pays her a visit…

The painting in question: The Mother and Sister of the Artist (1869-70) by Berthe Morisot (and Manet?) National Gallery of Art

Extract from Paris in Ruins

It was a Saturday, shortly before the deadline for submissions. Manet asked Morisot how she was getting on. “Seeing that I felt dubious,” she reported, “he said to me enthusiastically, ‘Tomorrow, after I have sent off my pictures, I shall come to see yours, and you may put yourself in my hands. I shall tell you what needs to be done.’ ”

Berthe’s complicated feelings for Manet were layered over insecurities about her painting. This painting in particular had given her lots of trouble, and her anxiety was heightened somewhat by vague feelings of jealousy over Manet’s developing relationship with Eva Gonzalès. But he seemed to grasp none of this. And what he did next was so painful to Morisot that it stayed with her for years.

He came by the Morisot home at about one o’clock, as he had promised, full of confidence and good cheer. The two painters went out to Morisot’s studio at the back and stood together in front of the painting on the easel. Initially, Manet was positive. He found the painting “very good”, he said. But the lower part of the dress wasn’t quite working, he opined. Before she could say anything, he picked up her brushes and put in “a few accents”. When Manet had taken a brush to Bazille’s Studio on the Rue de la Condamine, Bazille had taken it as a sign of friendship. But Berthe was in a different place and wasn’t expecting what came next. The brushstrokes looked “very well,” she reported to [her sister] Edma, but then her misfortunes began.

“Once started, nothing could stop him; from the skirt he went to the bust, from the bust to the head, from the head to the background. He cracked a thousand jokes, laughed like a madman, handed me the palette, took it back; finally, by five o’clock in the afternoon we had made the prettiest caricature that was ever seen.” The carter, who had the job of taking the finished painting from the studio to the Salon jury, was waiting, so Manet made Morisot put it on the handcart, and off it went. “And now I am left confounded,” Morisot wrote. “My only hope is that I shall be rejected.” Her mother, she added, was “in ecstasies,” finding it all very amusing, “but I find it agonising”.

• Sebastian Smee, Paris in Ruins: The Siege, the Commune and the Birth of Impressionism, Oneworld (UK) and Norton (US), 384pp, £25/$35