In the unevenly told story of slavery in the US, the shipwreck Clotilda, near Mobile, Alabama, stands out for its link between the forces of oppression and resilience. It is a historically rich site that physically connects centuries of the transatlantic slave trade to the people it enslaved. And now the Alabama Historical Commission (AHC), which a few years ago confirmed the identity of the ship that lies submerged in the Mobile River, is recommending that the wreck be preserved in situ to safeguard this important cultural heritage site.

The facts of the Clotilda mission and its aftermath are told through oral histories, documents, photographs and newspaper accounts. The ship enabled the illegal transport of Africans from Ouidah in present-day Benin to Mobile in 1860, even though the US had banned the trafficking of enslaved people into the country in 1807. The ship was burned and scuttled in an attempt to hide a criminal act. Aboard were 110 men, women and children as young as two years old who survived and endured slavery until they were officially freed at the end of the American Civil War five years later.

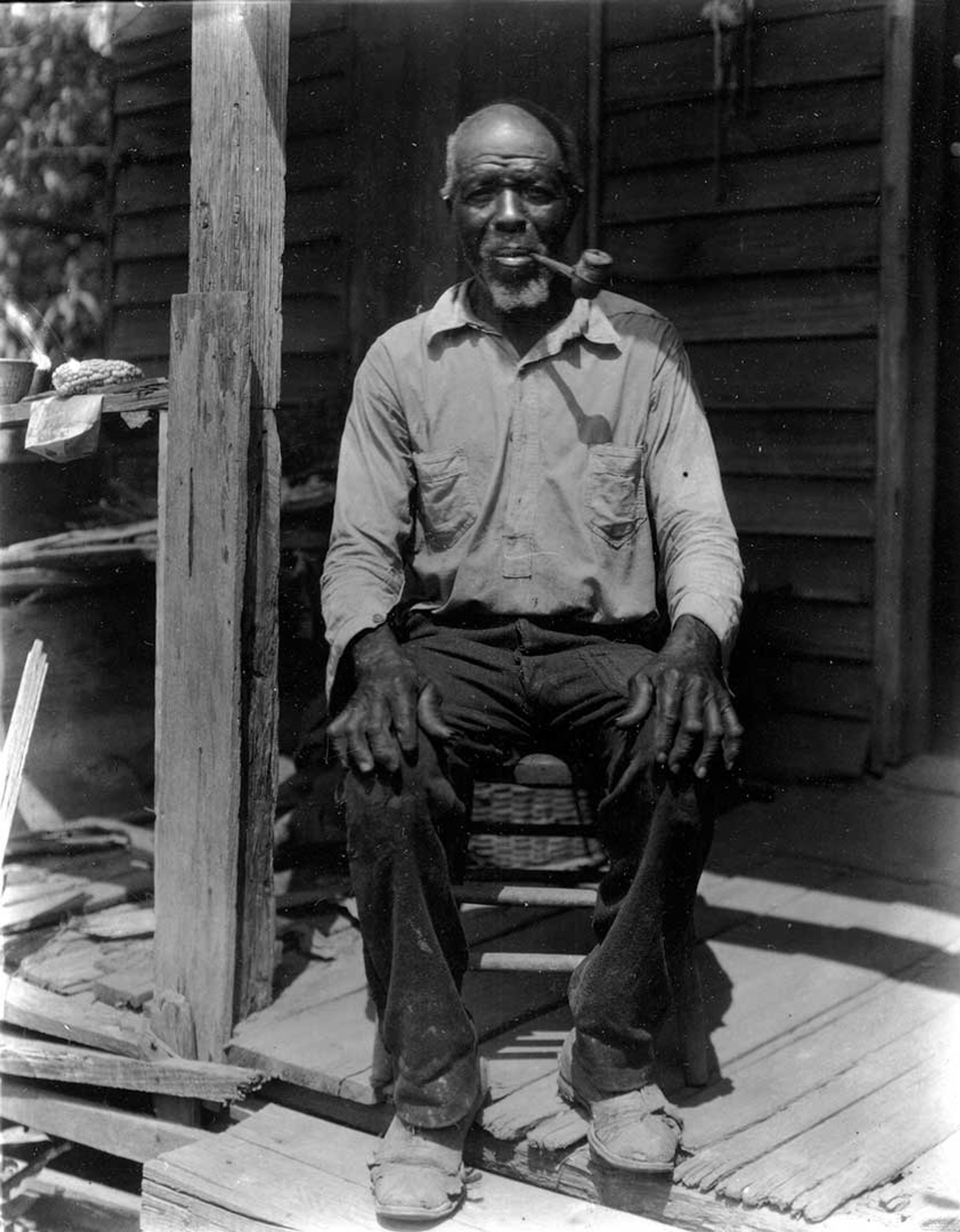

Around a third of the survivors remained in Mobile and rebuilt their lives, buying land and establishing Africatown, a community where they lived, worshipped and educated their children. Among the best-known Clotilda survivors was Kossola (aka Cudjo Lewis), who lived into his 90s and was interviewed by the writer and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston for her book Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo”—posthumously published in 2018.

Jeremy Ellis is a former president of the Clotilda Descendants Association whose ancestors Rosalie (Rose) and Kupollee (Pollee) Allen were trafficked aboard the Clotilda. Pollee was a beekeeper, a vegetable gardener and one of Africatown’s early governors. Ellis grew up learning of his family’s history from his grandmother and honouring his ancestors long before the shipwreck was verified in 2019.

Ellis tells The Art Newspaper that the interest in the shipwreck has shifted attention away from what is important about this history. “The focus has been, in most instances, on the ship and Africatown and what it is currently experiencing,” he says. “Very seldom has the conversation focused on the people who were on the ship and that started that community. Part of my responsibility is to say, ‘Yes, the ship is important, and it continues to play a role in this truth. But now that I have your attention, let’s talk about my ancestors. Let’s talk about their resiliency and what they’ve experienced.’ All of that plays a part, but it’s important that, as we’re talking about the ship, we also use that opportunity to uplift the 110, those survivors, and tell their truth.”

Archival research has shown that the medium-size schooner had a hold just large enough for a man to stand upright. However, more disturbing information has recently come to light, following a dive into an exposed section of the hull by James Delgado, the site’s principal investigator, and two divers from Diving With a Purpose—an international organisation that studies and protects submerged cultural resources from the African Diaspora. The team revealed modifications to the interior that separated the hold into confinements that Delgado describes as “coffin-like”.

Ellis had previously imagined his ancestors seated and chained in the hold. “But from the conversations I’ve had with Jim Delgado, we believe that they were essentially stacked into them. So my ancestors were being placed on planks, side by side. Imagine 55 on one side, 55 on the other side, stack by stack. That was very crushing to me,” Ellis says.

In situ preservation to safeguard the site

About a mile from the Mobile River is Africatown, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2012. Established by 1870, it is home to historic churches and the Old Plateau Cemetery, where many Clotilda survivors and their descendants are buried. It also hosts the Africatown Heritage House and its exhibition that tells the story of the 110 people aboard the ship through West African cultural artefacts and historical documents such as marriage certificates, land deeds and photographs. A multimedia naming wall memorialises the 35 known survivors and each of the 75 unknowns through descendants’ voices.

Unique to this exhibition is the display of several remnants from the schooner in wet aquarium tanks. These items were recovered during the identification of the wreck and have not yet been professionally conserved. They are held in their submerged state in treated water, giving visitors a near-tangible connection to the ship.

A place of deep spiritual connection

As an archaeological site, the Clotilda shipwreck is both of exceptional national significance and a place of deep spiritual and cultural connection. Current best practices call for its in situ preservation in order to safeguard the wreck and its setting, preserving the site’s integrity for future research and designations. At about 14ft deep, the Clotilda’s location in shallow, brackish waters makes it highly vulnerable. In the 164 years since its sinking, the Clotilda has endured damage from other ships as well as logs, vandalism by dynamite, sediment scouring and colonisation by barnacles, bacteria and marine borers.

These environmental stressors have had varying and cumulative effects on the materials of the ship. The vessel’s oak beams, southern pine decking, iron fasteners and nails (some with star-shaped heads) are in varying states of degradation, depending on their exposure to the elements, says Stacye Hathorn, an archaeologist for the AHC. The nails may be intact or corroded into crusted casts of themselves. One recovered timber-plank fragment was partially buried in the riverbed, Hathorn says. “The top half had barnacles all over it. It had been eaten by shipworms. It’s this soft, almost cheese-like consistency through the wood. But what was beneath the sediment could have been planed yesterday,” she adds. “It has sharp edges. There are even saw marks on it—you can see the wood grain.”

Kossola (also known as Cudjo Lewis) was one of the last survivors from the Clotilda’s grim journey from Africa in 1860. He was in his 90s when he died in 1935

There are few calls to raise the ship, which would be costly and likely damage the vessel. It is standard practice to leave shipwrecks in place, because their resting site is part of their story. But the AHC’s report warns that, without further protective measures, the Clotilda will be at risk of irreversible damage. It recommends that the wreck be buffered with poles or barriers and reburied in a protective layer of sediment, with long-term monitoring of the site.

Above the waterline, the Clotilda is already a place for visiting and remembering. Many would like to see the construction of a memorial, which is mentioned in the AHC report as an appropriate next step, though there are no funds or plans in place for it yet.

Ellis hopes that advanced technologies can be tapped to give descendants and the public an experiential connection with the Clotilda—such as using 3D scanning to create life-size replicas or employing underwater cameras to bring images of the wreck to the public.

“We should also have some sort of water memorial out at the location of the Clotilda that honours those 110 survivors,” Ellis says. “What does that look like? I think we again have to think outside the box. We have to look at what other water memorials have done to commemorate, honour and celebrate survivors.”