The Sundance Film Festival often includes a mix of biopics about innovators in the arts, investigative art world documentaries or scripted features set around contemporary art or clubby connoisseurs. Not this year, when films screening as part of the all-virtual festival (until 30 January) range through architecture, visual innovation and archaeology.

At is core, Descendant is about archaeology. The ship Clotilda, the last to bring enslaved people to the US, was burned by its operators north of Mobile, Alabama in 1860 after they unloaded around 110 enslaved Africans. The slave traders lied about where the Clotilda sank, hoping that the evidence of their crime would never be found.

Many descendants of those Africans brought to the American South against their will still live in the Mobile district called Africatown, and trace their lineage to the Clotilda. One of the Africans was Cudjoe Lewis (1840-1935), whose story, told before he died to author and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston, was published in Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo (2018). Whites descended from Timothy Meaher—a Mobile businessman who financed the Clotilda on a bet that he could get away with it even though importing enslaved people had been illegal since 1807—didn’t talk about it much.

Margaret Brown’s documentary shifts back and forth in time, tracking the archaeology of a community reconstructed without the slave vessel itself. When the submerged remains of the Clotilda are identified in 2019, that story advances, but the broader challenge of preservation is put to the test. Africatown is hemmed in by industry that belches out pollution and threatens its inhabitants, even as they plan for a new museum where tourists would pay to see the ship’s preserved remains. The challenge today is preserving people, now that the remnants of their enslaved ancestors’ voyage to America are there for the world to see.

A scene from Riotsville, USA by Sierra Pettengill Courtesy Sundance Film Festival

Riotsville, USA, by Sierra Pettengill, is about architecture designed by the US military in the 1960s to preserve order. Fake towns were built on army bases and served as stage sets for “riots” with all the amateurism of small-town theater, where soldiers dressed as protesters stormed the “streets” and armed troops were trained to quell the protests. High-level military leadership applauded the “clashes” in spectator seating.

Footage of exercises filmed by the military, and now publicly available, are packed with unintentional humor. Structures are cruder than sets for low-budget movies. The “rioters” are overwhelmingly white and noticeably wholesome, although some wear cheap makeshift wigs.

Some of the same officers who viewed the clashes in the “towns” oversaw law enforcement units deployed to crush actual riots at the political conventions where candidates for president were nominated in the summer of 1968.

The footage speaks for itself, including violent demonstrations and forums on a public television channel (then called Public Broadcast Laboratory, or PBL), where Black leaders discussed underlying causes of actual riots in US cities. PBL, a project created by the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), was disbanded when the Ford Foundation, a major funder, found its coverage too political.

Decades later, soldiers trained in a dozen Afghan and Iraqi “towns”, one with almost 600 buildings, on a base outside Barstow, California, near Las Vegas.

A scene from All That Breathes by Shaunak Sen Courtesy Sundance Film Festival

A visually stunning and poignant documentary at this year’s festival that might escape attention is All That Breathes, directed by Shaunak Sen. In Delhi, the world’s most polluted city, the film follows a team of Muslim men who are committed to saving injured birds, especially the black kite, which the dominant Hindu population scorns because it eats meat. With no resources and meagre technology, and with resentment from Hindus, the men tend to the birds every day in a process that Sen observes at close range.

The larger context sets the tone in a city so stricken by toxic air that humans and all kinds of animals are jammed together in what, through Sen’s camera, seems like a post-natural environment. Enterprising monkeys use the strands of wires connecting buildings to sources of electricity into canopies through which they travel from place to place. At dusk, all sorts of non-human life—from rats to pigs to cows—scramble alongside people sleeping outside, producing an immersive “city as terrarium” effect. As the “kite brothers” work, cringing at radio reports of murdered Muslims, Sen cuts away to meditative closeups of silent birds, portraits of seemingly stoic observers waiting to be returned to a dangerous sky. Dingy and poetic, All That Breathes is about a shared destiny in an unwelcoming place.

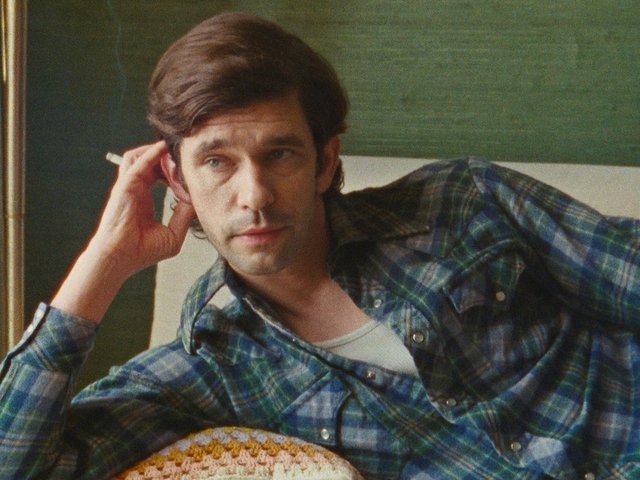

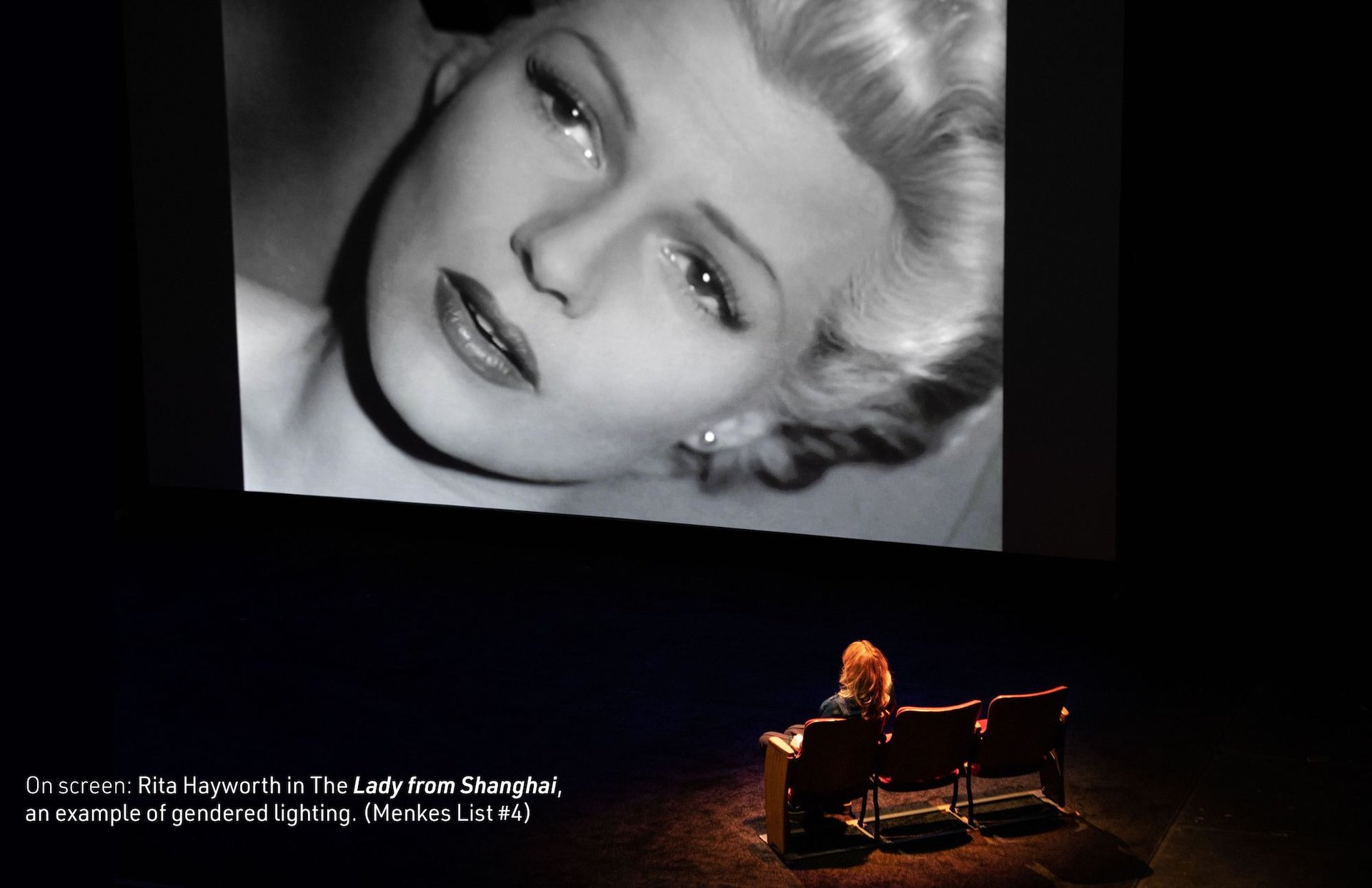

A scene from Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power by Nina Menkes Courtesy Sundance Film Festival

Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power by the veteran independent director Nina Menkes might as well be called “An Inconvenient Truth 5.0”. Taking the stage lecture format of Al Gore’s ecological plea for engagement, recently applied to another urgent subject in Who We Are: A Chronicle of Race in America by Jeffery Robinson, Menkes marches through cinema, mostly American, arguing that a perspective in the mostly male profession produces ways of seeing that then lead to sexual discrimination, harassment and assault.

Menke’s point of departure is the notion of the male gaze, a dynamic whereby men use images and footage of women for men’s pleasure. The concept was put forth in the writing of film theorist Laura Mulvey, who speaks onscreen, along with many other women critics.

Few men are spared in Menkes’s survey—not Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, Ridley Scott, Spike Lee, Jean-Luc Godard, Abdellatif Kechiche, or even, god forbid, Sundance’s well-meaning founder Robert Redford in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. And no men here offer opinions on film history or films as they are made today. Are there men who have at least gotten things half-right? If we ever learn that, it will be in a different lecture.

There are positive signs for Menkes. She likes Nomadland, by Chloé Zhao. And she is echoed throughout Brainwashed by accomplished young critics. The Sundance Film Festival, with mostly women at the helm, is itself proof that management can also change. Yet experience shows us that progress in the movie industry can be as slow as an Eric Rohmer love story.

- The 2022 Sundance Film Festival, online only, continues until 30 January