Soon after the 2019 fire at Notre-Dame, President Emmanuel Macron pledged to “build an even more beautiful cathedral”, announcing an international competition for the design of a new spire. The outcry was so great that the president was forced to drop his grand ambitions, and pledge that the spire would be rebuilt as it was before the blaze.

The 96m-high structure was designed in the 19th century by Jean-Baptiste Lassus and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, to replace a lower bell tower damaged and dismantled in the 1780s. Macron claimed he had been convinced by the experts, but he also realised that a new spire would delay the reconstruction, which he promised would be completed in five years.

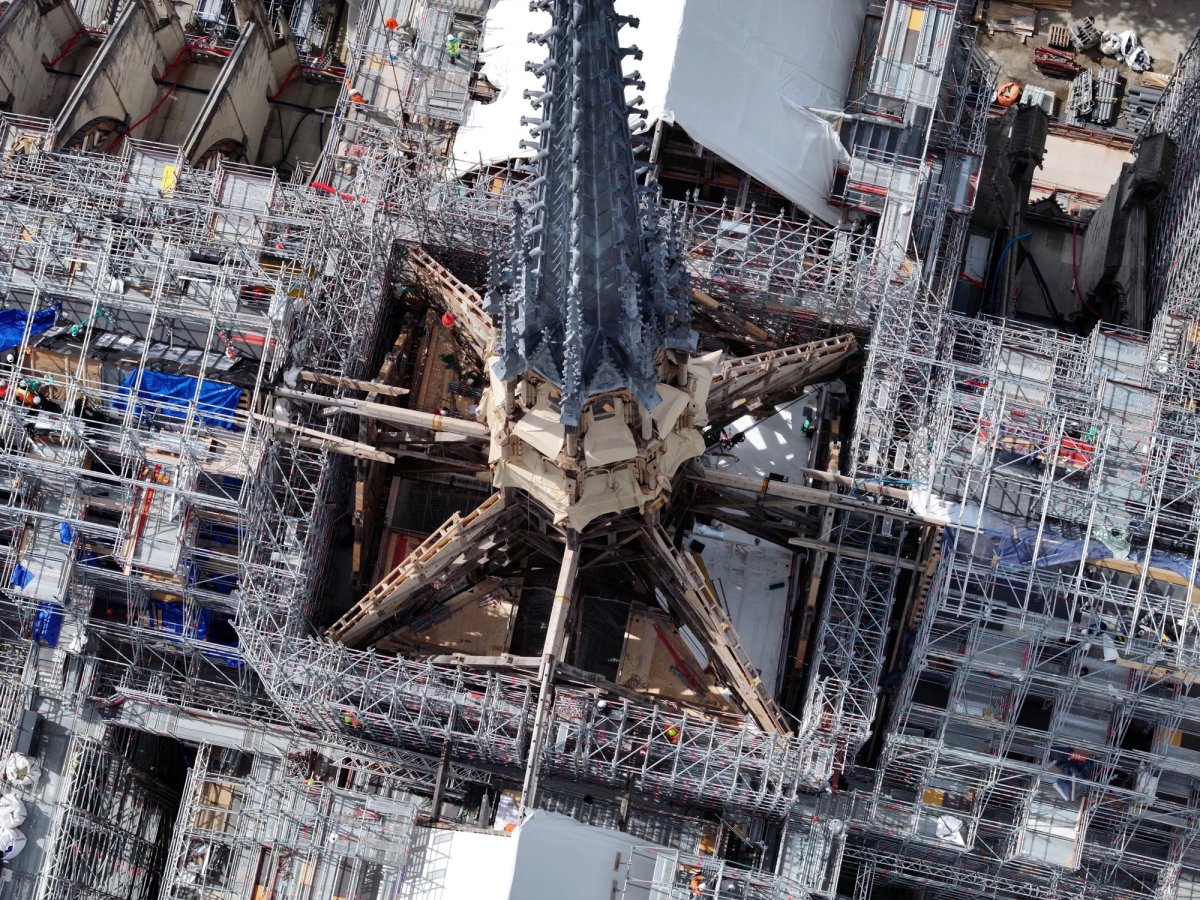

Four days before the president’s announcement, the National Heritage and Architecture Commission had unanimously approved a 3,000-page plan to rebuild the monument according to Viollet-le-Duc’s plans, using ancient materials such as oak for the framework and lead for the roofing. The president subsequently expressed the hope that “a contemporary architectural gesture” could find its place in the grounds surrounding the cathedral. But this also fell on deaf ears. The area belongs to the city of Paris and it chose to leave the square in front of the cathedral empty.

Five years later, Macron tried again to make his mark on the rebuilding of the monument. This time, against the unanimous verdict of the same National Heritage Commission, he ordered the removal of the stained-glass windows designed by Viollet-le-Duc from six of the chapels and commissioned modern creations to replace them. Heritage associations, scholars and architects protested against this fait du prince, which violated the principles of the 1964 Venice Charter. A petition to keep Viollet-le-Duc’s windows in place has drawn 234,000 signatures. As the government has decided to move ahead, heritage groups have pledged to take the issue to court.

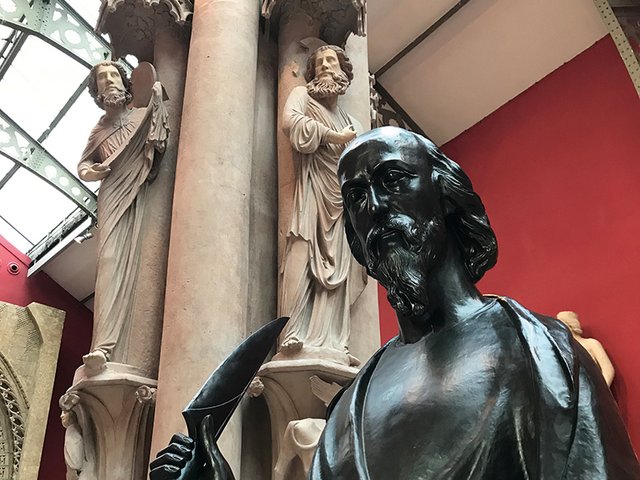

The main beneficiary of this quarrel between the ancients and the moderns is Viollet-le-Duc, whose work has been thrust into the spotlight. Many who believed Notre-Dame’s spire, or its spectacular gargoyles and griffins were inherited from the Middle Ages now know his name. Among the 19th-century architects devoted to saving France’s monuments, Viollet-le-Duc is the most prominent, if only because he laid down, in voluminous prose, the theory of what was known as the “neo-Gothic” movement (a label he was much opposed to).

Viollet-le-Duc left more than 100 books, notably the ten-volume Dictionary of French Architecture from the 11th to the 16th century including 3,700 drawings, which forms the richest iconographic lexicon on the Middle Ages. “The importance of his writings attracted unconditional admirers, but also vindictive adversaries who made him the scapegoat of an imaginary Gothic party,” writes Françoise Bercé in her monograph on the artist.

The artist Auguste Rodin was among those who accused Viollet-le-Duc of destroying Notre-Dame with his fantasies. In 1914, a newspaper claimed that, guided by a “fury of logic” to reconstitute the past, Viollet-le-Duc “delivered a cathedral which had never existed, at any time”.

His rehabilitation started among a limited circle of scholars in the 1960s and was cemented by an exhibition curated by Bruno Foucart in 1979 for the centenary of his death, followed by the republication of his texts.

“Liberated from Victor Hugo’s romanticism, his vision of an art total, supported by a rigorous observation of the Middle Age, is better understood. He was after all a precursor of the modern style,” says the art historian Thierry Crépin-Leblond, who has just published a book on Notre-Dame.

"Through this last restoration, Viollet-le-Duc has been recognised as the new founder of the cathedral that he had dramatically reshaped. According to the rules of conservation, his heritage must be respected because he is undoubtedly part of the monument’s history,” says the architect and former head of Unesco’s cultural division Francesco Bandarin. But Bandarin is also among those who fears the pendulum may have swung too far. He wonders “why the idea of asking living artists to renew the windows triggers such a violent reaction”.

The architecture historian Alexandre Gady, also an author of a book on the cathedral, warns that such a purist response can lead to wrong choices. He regrets the reconstruction of “such a heavy spire, which became a mega-chimney in 2019, and the use of materials such as wood and lead, which are so dangerous in cases of fire”. He questions why the framework, “which is invisible”, was not rebuilt with a modern design and more secure materials, as in other places such as Reims or Nantes.

In the words of Bercé, Viollet-le-Duc—once vilified, then glorified—has now “become untouchable”. There is a price to pay for this: a risk of an absolute protection of 19th-century cultural heritage, even though the materials used, and the style of the age, were often mediocre.