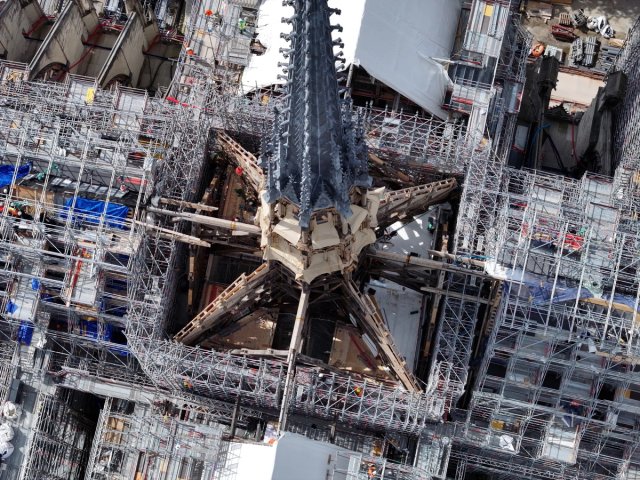

One of the greatest casualties of the Notre-Dame fire was the wooden spire. But fate had other ideas for the statues at the structure’s base, a set of copper sculptures representing the Twelve Apostles and four New Testament Evangelists. Had the blaze occured just a few days earlier, these works would have likely met their own grim demise. Fortunately, they had been removed for restoration before the fire broke out and will be placed back on the cathedral next year.

The statues were designed in 1857 by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc as part of his radical restoration of the cathedral—of which the soaring 96m spire was one of the most dramatic symbols. The figures, modelled by the sculptor Adolphe Victor Geoffroy-Dechaume, were arranged in four diagonal lines around the narrow structure, each emblem of an evangelist topped by three apostles. One apostle, Thomas, the patron saint of architects—designed after Viollet-le-Duc’s own image—was shown staring up at the spire, atop which sits a rooster containing relics. The result, says Michael T. Davis, an art history professor emeritus at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts who has written extensively on Notre-Dame, is a composition “that really crystallised the fundamental mission of the cathedral as a site of spiritual transcendence”.

The sculptures, formed out of 1mm-thick copper sheets fixed on steel armatures, were being restored by the conservation firm Socra when the fire broke out in 2019.

The firm has replaced parts of the frames damaged by galvanic corrosion (caused by contact between the two metals), proofed the structures from any future such damage, and repaired deformations to the copper skins through heating and hammering, among other things. There have been interesting discoveries in the process: bullet holes, for example, were found in the figure representing the evangelist Saint Mark, likely dating back to the Second World War.

Perhaps the most visually remarkable aspect of the work has been the decision to return the statues to their original chocolate -brown colour. Over the years they had turned green because of oxidation; Socra cleaned them, gave them a new patina—using a product called Barège, a potassium sulphide—and added a colourless wax that should preserve their hue for around 15 years. “People will certainly be surprised,” says Richard Boyer, the general director of Socra.

Seeing the sculptures back in position in the first half of 2025—below a new golden rooster, the original having been remarkably recovered among debris but now housed in a museum—will indeed be a striking sight. But their survival has an even wider significance, having played into debates about whether to revive Viollet-le-Duc’s spire or use a contemporary design. As Michael Hall, the former editor of The Burlington Magazine and a writer on architecture and the Gothic revival, tells The Art Newspaper: “The happy chance that the figures of the apostles and evangelists had been removed for repair just four days before the fire helped swing the decision to undertake an accurate restoration of Viollet-le-Duc’s spire, which is so prominent a part of the cathedral’s world-famous silhouette.”

For Davis, the decision to bring the 19th-century spire—and its statues—back to life goes even as far as creating a through line back to Notre-Dame’s Medieval origins. Referencing Viollet-le-Duc’s passion for Gothic architecture, he says: “I think [restoring the spire] was the right decision. With it, you can almost look through the lens of Viollet-le-Duc’s vision back to the Middle Ages.”