Have you ever been influenced?

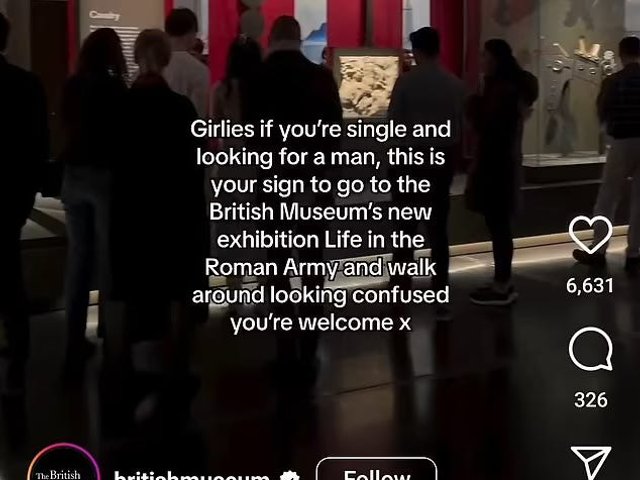

I certainly have. In the past year alone, I have bought a bathing suit, seen an Off-Broadway play and gone to a new Brooklyn restaurant after people I follow on Instagram posted enthusiastic reviews. So perhaps it is not surprising that, as museums face dwindling attendance and aging audiences, some are wondering: are influencers the solution they have been looking for?

Some people certainly think so. Elizabeth Furze, the chief executive of the advertising agency AKA, has been advocating for clients to consider influencers’ vast potential for several years now. She cites a recent study from the survey research company Morning Consult that found that Gen Z audiences “respond far more positively to content shared by another human that they trust than they do to an ad”, she says. (The same study found that one in four Gen Z adults follows more than 50 influencers on social media.) If influencers—or content creators, Furze informs me they prefer to be called—“can help make museums feel more relevant and accessible to young audiences, to me, it’s a no-brainer”, she says.

Not everyone agrees. The digital strategist JiaJia Fei notes that paid influencer marketing could make the museum-going experience feel too transactional—like a product to be bought and sold. “Museums are non-commercial entities,” she says. “Adding the layer of advertising on top seems inauthentic to me.”

Slippery slope?

The influencer conundrum is just one expression of a broader set of challenges museums are wrestling with today. What is the place of the institutional voice in our hyper-personalised, hyper-fragmented media landscape? Is it better to control the narrative or allow others to tell your story and risk misinterpretation? Is it possible to reach new audiences without sacrificing scholarship and rigour—and, perhaps more importantly, without coming off as desperate?

Museums first began engaging with content creators around a decade ago, before the term “influencer marketing” even existed. In 2013, Fei, then a marketing manager for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, began inviting people with large social-media followings to the museum’s press previews. Before long, images of the Guggenheim’s James Turrell show—specifically, the Frank Lloyd Wright rotunda awash in rich colour—were everywhere online. The development spawned a wave of think pieces about how museums were on a slippery slope towards becoming shallow funhouses.

A decade later, museums have not been swallowed up by the Instagram monster, and they have not swapped wall text for wavy mirrors and flattering lighting. But we may have the ever-changing algorithm, rather than curatorial restraint, to thank for that. Social-media platforms began prioritising video, candid storytelling and narration over static, artfully composed imagery. This shift let the air out of the Big Fun Art craze. Perhaps more importantly, it changed audiences’ relationships with the people they follow online, making their digital interactions feel more intimate and personal.

Mini-influencers pack just as big a punch

With this transition came a tiered economy for influencer marketing. While many associate the influencer business with Kim Kardashian charging upwards of $1m per post, Furze says that “nano-influencers” (with fewer than 10,000 followers) and “micro-influencers” (with between 10,000 and 100,000 followers) can be just as effective for institutions that want to target specific audiences. According to Furze, the former might charge between $250 and $500 for a post; the latter, between $2,500 and $5,000. A “macro-influencer”—someone with more than 100,000 followers—typically asks for between $15,000 and $50,000.

At the moment, few museums are paying content creators for elaborate campaigns the way the beauty, travel or fashion industries have been doing for years. But more institutions are investing in special opportunities for influencers, including private previews, meet-and-greets and after-hours events. One influencer told me, for example, that the Metropolitan Museum of Art recently held a creators’ hour at a time when the museum is normally closed. “It helps for us to have dedicated time and space in the exhibit,” says Charlene Wang, a content creator who focuses on New York City culture and events. “That makes it feel special.”

For a recent show about China’s Bronze Age, the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco invited a group of Bay Area content creators who specialise in textile and costume design for a private tour with the exhibition’s curator. “At the end of the day, it makes my job easier,” says Alisa Wong, the museum’s digital marketing co-ordinator. “It’s less digital marketing I have to do, and we’re working with creators who advocate for us.” Wong estimates that the museum now dedicates 40% of its digital-marketing strategy to creators and influencers (the remainder goes towards paid digital ads and organic content on its own website and social-media channels).

The Arts Insider programme pays influencers to post content about institutions like the Frick and the Met

Photo: Marc Franklin, courtesy of AKA

‘Leap of faith’

Not everyone is on board with this approach. “Some marketing departments at museums are really enthused about having influencers come in, and some—the old guard—are not,” says Pari Ehsan, who pairs avant-garde fashions with art on her account @PariDust. She says she has struggled to shoot content in some exhibitions because museums perceive her work as conflicting with their fashion-industry sponsors.

“There is a leap of faith that traditional museums and marketers need to make in terms of accepting the potential lessening of the control that they would have over the content,” Furze admits. “I think it will become necessary.”

To help clients take the leap, AKA established the Arts Insider programme, a network of dozens of influencers who are paid a modest stipend in exchange for two Instagram posts per month about client offerings. (The company’s roster includes the Met Museum, the Museum of Sex, the Frick Collection, 92nd Street Y and Atlantic Theater Company, among many others.) The creators have approximately 15 million followers between them and produce around 60 posts per month. The Arts Insider programme is bundled into AKA’s full-service contract, easing clients into the prospect of engaging with content creators at no additional fee.

Of course, influencers are far from a silver bullet. Their impact is often indirect and hard to quantify. The photography museum Fotografiska was among the institutions most committed to the strategy, and it recently announced it would close its splashy New York branch. (It has yet to announce a new location in the city.) The best argument I have heard against paying influencers is that doing so may syphon money from the already minimal budgets that museums have for conventional media advertising, which supports independent publishing. But if museums want to grow their audiences, they are going to need to figure out how to reach people where they are—and increasingly, whether we like it or not, that means reaching them on other people’s social media.