Édouard Manet, in constant pain during his last years, painted the same motif over and over again: cut flowers in a glass vase, a profusion of whites, reds, and pinks, an affirmation of life even as their creator was dying. But Manet also took care to depict the stems inside the vase below, a blur of greens and blacks and browns, life disintegrating back into the primordial slime.

His bouquets mesmerised John Berger (1926-2017), the British art critic extraordinaire, painter, novelist and poet. In letters he exchanged towards the end of his life with his son Yves (50 years his junior and also a painter), he devoted several ecstatic passages to them. Manet’s flowers existed, John said, where he was now finding himself, too: “on the edge of the world”.

The end of life

The phrase was not actually John’s. Yves had floated it first, after praising Manet for having captured “like no others the dialectic between life and death”. John agreed, but went on, precise observer that he was, to clarify why exactly these bouquets seemed so ambiguous. Manet had been, he wrote, “as fascinated and spellbound by what he saw through the glass… as by what he saw blossoming out of it”. His cut-off stems, properly considered, beckon us “to the domain of the nameless”, the murky beginning or, in this case, the end of life. Yves, in his next letter, embraced John’s interpretation and added a suggestion of his own: “Let us both visit a cemetery,” he said, “you near Paris and me in a village here.” (Yves was writing from his house in the French Alps.) “Let’s try to look, listen and feel.”

Encouraging your 89-year-old father to visit a graveyard might strike some readers as a little off-key. But in their letters, John and Yves sail blithely past proprieties and orthodoxies. One would expect the elder Berger, author of such influential books as Ways of Seeing (1972) and About Looking (1980), to lord it over his much younger son, but the correspondents remain on equal terms throughout. And both share the conviction, succinctly expressed by Yves, that art writing today is pretty much “a catastrophe”—an incentive to do things differently.

What father and son are doing in these letters is indeed quite different from the careful art-historical emphasis on historical context, tradition, and artistic innovation and intention. Consider the unusual pairings they propose, juxtaposing Francisco Goya’s La maja vestida (the clothed Maja, around 1800-07) for example, with Vincent Van Gogh’s Still Life with Bible (1885), which will make you realise, John contends, what a reclining woman and an open book have in common.

But Yves, in his next letter, complicates matters by adding Chaïm Soutine’s Le bœuf écorché (around 1924) to the mix, a painting of a bloody, eviscerated cattle carcass. Openness, it appears, is a matter of degree and perspective. In another pairing, the Bergers place William Coldstream’s Seated Nude (1952-53), a portrait of a young woman on a chair “waiting… for what life will give her”, next to Pierre Bonnard’s L’eau de Cologne (around 1908-09), a portrait of the artist’s companion Marthe contentedly basking in the sunlight. One artist’s scepticism is another one’s confidence.

Intense repartee

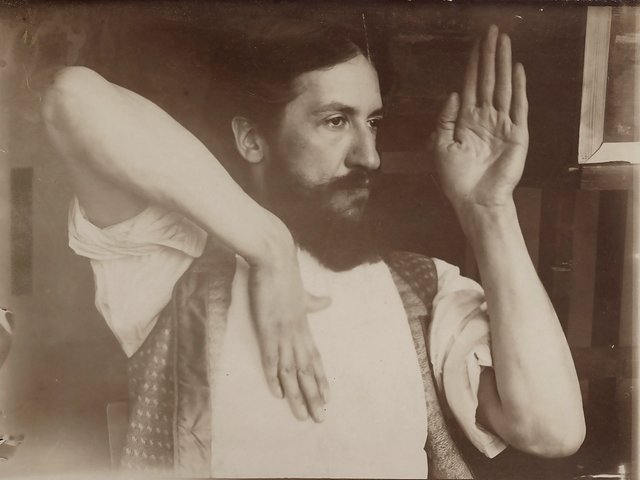

“Over to you” was what the Bergers would yell at each other during their table tennis games, and it is a delight to see a similarly intense repartee at work in their letters. The consummate stylist, John is at his best when he recreates encounters with artists he has known, such as Oskar Kokoschka, whom he once joined on a London rooftop, from where the exiled Austrian artist was painting the city as if he were “a migrant bird about to leave”. And Yves excels when he waxes lyrical about his own work, telling his father how he mixes his paints, for example, creating a “blanc de titane” (titanium white) as perfect and pure as the snow outside his window.

For both Bergers, art is about what we strain to see yet cannot fully grasp, a point reinforced by the gathering of the delicate sketches in the book’s appendix. In the most moving pairing, we see John’s ink portrait of Yves holding his dead rabbit—the contours of the animal’s limp body melding with that of its sorrowing owner—opposite a photograph of a rabbit Yves had drawn in the snow outside his home: an outline only, made more poignant by our realisation that it has already disappeared.

• John Berger and Yves Berger, Over to You: Letters Between a Father and Son, Pantheon Books, 102pp, 53 colour illustrations, $25/£20 (hb), published 12 November

• Christoph Irmscher is a critic and biographer