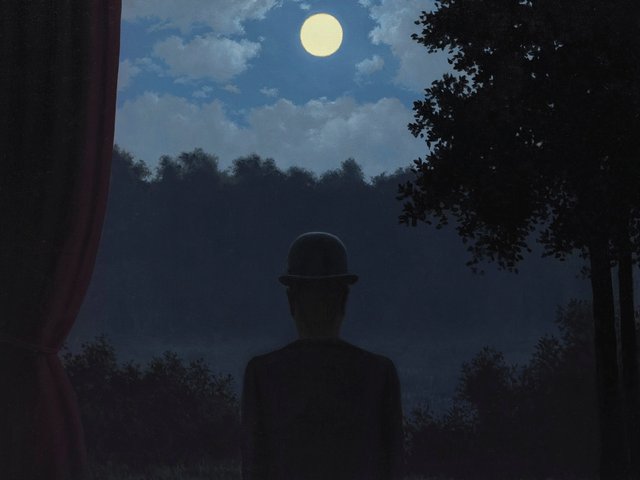

Celebrated Belgian surrealist René Magritte (1898-1967) was famously opaque. His public image—the average man in suit and hat, dwelling in the suburban anonymity of Brussels—seemed designed to deflect inquiry into his personal life. He refused to explain his paintings, which would have dispelled their poetic mystery. Any biographer of Magritte has to confront the subject’s conscious reticence.

Alex Danchev, acclaimed biographer of Braque and Cézanne, died before completing the final chapter of this biography. It was finished by Sarah Whitfield, co-author/editor of the six-volume Magritte catalogue raisonné (1992-2012). We are in safe hands. Danchev’s familiarity with francophone culture and Whitfield’s decades of Magritte expertise shine through in this absorbing, masterful biography.

Much new material relates to Magritte’s childhood in Lessines, within Belguim’s Walloon region. It turns out that Magritte’s father, Léopold (a merchant tailor among other things) was a complicated character—a proud, materialistic, sacrilegious, aggressive, irreverent philanderer and social climber. He was mocked by his three unruly sons, who were seen collectively as a “bad lot” by locals. The four of them apparently tormented the mother, Régina, who died by drowning herself in the River Sambre. It is hard not to think less of Magritte père et fils in the light of Danchev’s descriptions of the mother’s suffering. The biography is informative on Magritte’s days at the Académie Royale in Brussels, where he studied under Constant Montald and took lessons with the versatile artist, illustrator and designer, Gisbert Combaz, less so about his short military service in the Belgian infantry (from late 1920 until mid-1921). In 1922, he married his childhood sweetheart, Georgette Berger—Danchev reports that others found her pretty but materialistic and shallow. That same year, Magritte saw for the first time the work of the “metaphysical” artist and major influence on the surrealist movement, Giorgio de Chirico. A sojourn in Paris (1927-30) did not result in a sustainable income as a painter and Magritte remained peripheral to the Parisian Surrealist group.

Forging the greats

While he stayed in London in 1937 (painting pictures for eccentric aristocrat Edward James’s ballroom), Magritte had a brief liaison with the British Surrealist Sheila Legge. At this time, Georgette had an affair that was serious enough for her to request a divorce. Eventually, the couple made it up and remained married. Although this was published previously, the biography summarises from multiple sources to give a more rounded view. What will surprise some is the fact that Magritte was a devoted visitor of brothels.

Danchev has uncovered more details about Magritte’s work as a forger during the Second World War. Magritte painted Old Masters (Titian and the 17th-century Dutchman Meindert Hobbema) and Moderns (Ernst, De Chirico, Klee, Braque, Picasso), which are fairly obvious fakes. Georgette was outraged when Marcel Mariën exposed this—and his own complicity as vendor—in print after Magritte’s death. She sued Mariën and lost. The tale of Magritte’s fake Titian is a great vignette. The fact that Magritte also dabbled with currency forgery will startle many readers.

Although one might argue with interpretation on some issues (Magritte’s political commitment, for one), there are no lapses in this lively biography. Magritte: A Life recounts the artist’s life in a sympathetic and comprehensive manner, never reducing the mystery of one of the most influential of modern artists. We await with eagerness an English edition of the Magritte letters.

• Alex Danchev (with Sarah Whitfield), Magritte: A Life, Pantheon, 464pp, 32 pages of colour illustrations, black-and-white illustrations throughout, $45 (hb), published 30 November 2021 (UK edition, Profile Books, £30 (hb), published 18 November 2021)

• Alexander Adams is an artist and author. His book Magritte is published next year by Prestel