An encounter with the art of Hamad Butt is not without risk. In 1995, more than 100 people were evacuated from the Tate Gallery after iodine gas leaked from a crack in the glass sculpture Substance Sublimation Unit, one of three works that form the artist’s Familiars series (1992). Last year, that same museum (now Tate Britain) rehung its permanent collection and devoted an entire room to a version of Butt’s 1990 installation Transmission. Visitors were given safety goggles to protect their eyes from the ultraviolet light it emitted. To say these works evoke danger, and even death, is justified: the title of Transmission refers, in part, to Butt’s 1987 HIV diagnosis. He died of Aids-related illness in 1994, aged just 32.

Both Transmission and Familiars will be shown together in Apprehensions, the first survey of Butt’s career, at Dublin’s Irish Museum of Modern Art. The first significant exhibition of the British-Pakistani artist in more than two decades, it will bring together these hazardous installations with around 40 rarely seen paintings, drawings and etchings from his early career, plus archival material borrowed from the Tate and his posthumously published writings on fear, desire and his deteriorating health.

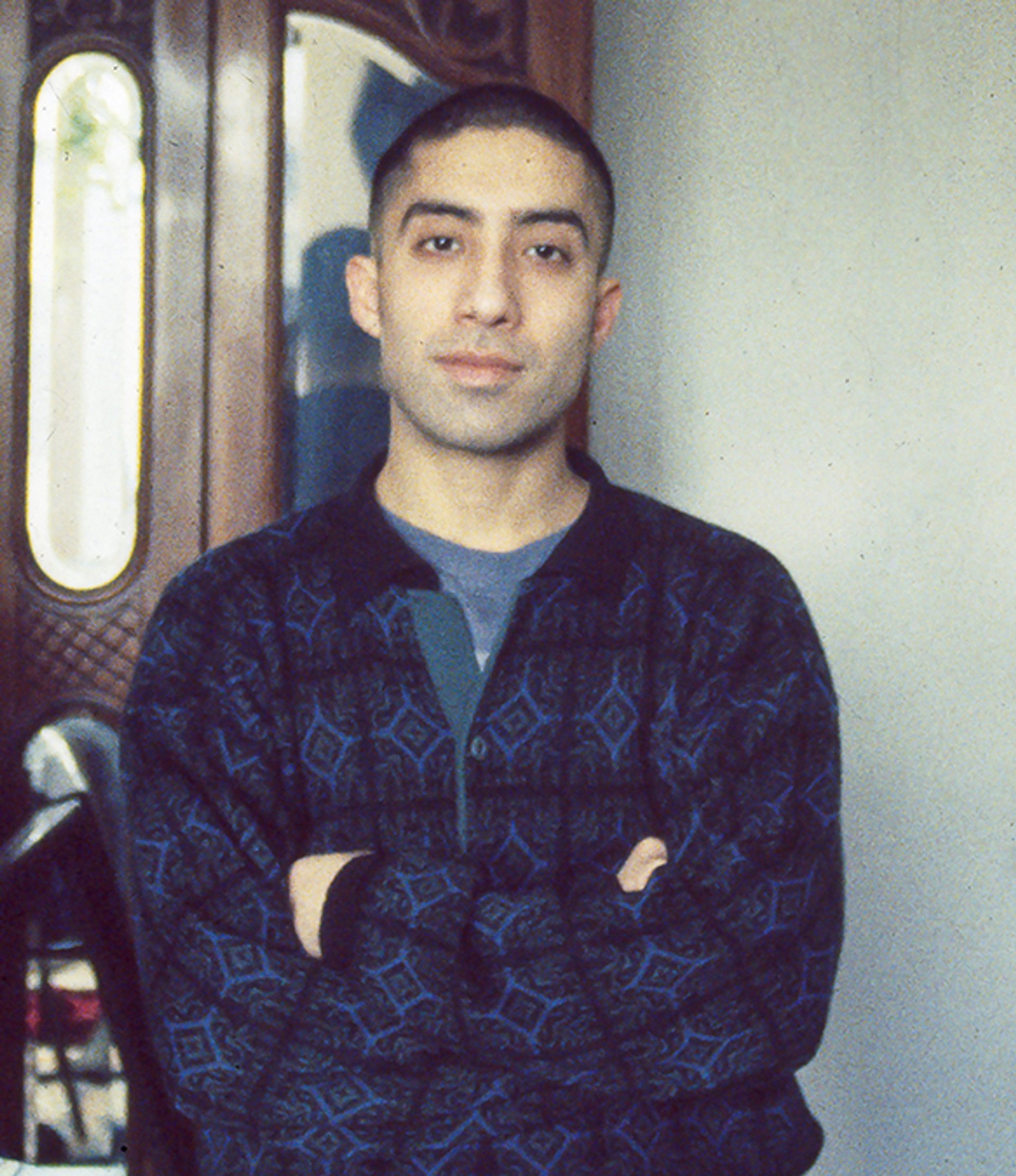

Hamad Butt turned to art after gaining a degree in chemistry Estate of Hamad Butt

Like many promising artists of that generation who contracted Aids, Butt is not well known to contemporary audiences, so the show is tasked with introducing viewers to his art and biography. Chiefly, he is presented as an artist making work in response to HIV. Doing so will “challenge the myth that British artists didn’t react to the Aids crisis—and if they did, they were Derek Jarman”, says the co-curator, Dominic Johnson. Unlike Jarman’s response to Aids, which is “more legible, due to its figurative and activist nature, as well as its closer resemblance to contemporaneous responses to Aids in North America, [Butt’s is more ] elliptical, conceptual and subtle”, Johnson says.

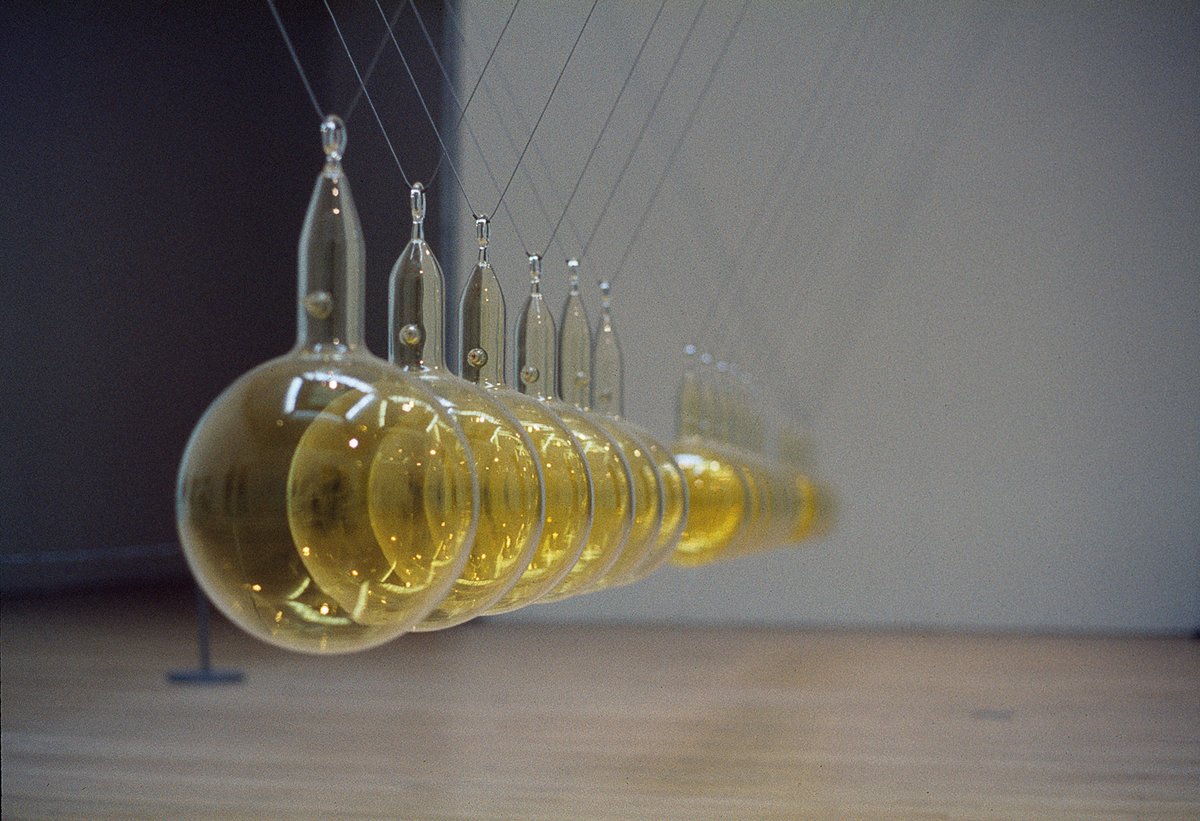

Butt gained a degree in chemistry before pursuing art, and his diagnosis prompted him to consider how a language of fear around sex and disease could be conveyed through science. Familiars is designed around three noble gases that are visually striking but also deadly at room temperature, with each part of the installation tempting a perilous interaction. In Cradle, named after the Newton’s cradle desk toy, 18 vacuum-sealed glass spheres are filled with lethal yellow-green chlorine gas. If smashed together, the lung-destroying substance would be released into the air.

Damien Hirst rivalry?

The exhibition sees the first full restaging of Transmission since its debut in Butt’s Goldsmith’s MA degree show in 1990. The full work includes a glass-fronted cabinet containing live flies that pupate, lay eggs and die over the course of a show. This reignites a tense moment between Butt and Damien Hirst, who were both at Goldsmith’s at the same time. A month after Butt showed Transmission, Hirst unveiled A Thousand Years (1990), a glass cube containing a calf’s head being consumed by fly maggots, which would help catapult him to fame. Butt later destroyed the cabinet in Transmission, and while it was never publicly acknowledged why he did this, “it is quite clear he was upset with Hirst”, Johnson says.

While comparing Hirst and Butt’s maggot works may emphasise their stark divide in fortune, it also underscores a difference in their styles and approaches. Hirst’s decomposing calf foregrounds shock and is aggressively literal, while Butt’s work is more esoteric and obscure, incorporating references to Islamic prayer circles, science fiction and the occult, among others subjects.

Hamad Butt; 'Transmission' (1990) Glass; steel; ultraviolet lights and electrical cables. Overall display dimensions variable. Tate. Presented by Jamal Butt 2019

This enigmatic tendency is seen in the title of the show, Apprehensions, which comes from Butt’s 1990 essay of the same name. In it he writes: “I want to exploit the word ‘apprehensions’ for its associations with arresting, grasping, understanding and fearing.” Such manifold meanings are typical of Butt’s work, which, according to Johnson, is “always cryptic, complex, layered, and enticing, bringing together a severe quality—that of the scientific investigation—with a more delicate, erotic, or perverse aspect”. If all that was an uneasy fit with the brasher sensibilities that dominated the Young British Artists (YBA) era, perhaps it will find a better reception today.

As the exhibition’s release reads: “Butt’s invocations of the end of the world are redolent in our own contaminated present—blighted (still) by pandemics, looming environmental disaster, migrant crises, and terror from the air.”

• Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin,

6 December-5 May 2025; Whitechapel Gallery, London, 4 June-7 September 2025