My best friend calls me a contrarian. Of course, I disagree. Nevertheless, once in a while, the mood to swim against the current strikes me. This mood came upon me recently, in the run up to what is commonly called ‘art week.’

London was all the art press could write about and frankly, I was tired of it. Surely, there must be excellent art on view outside London, during ‘art week.’ A quick search revealed that the Whitworth in Manchester was holding the first major survey exhibition of Barbara Walker’s work. Bingo.

I must confess that when I booked my train ticket, I felt rather virtuous. I was ascetically turning my back on the revels of Frieze and 1:54, in order to pursue a more egalitarian, less London-focused art world.

Barbara Walker, Untitled (2002)

It was a different story when I actually had to get up early to catch my train. What a bother to see some art, I grumbled as I trudged to my platform. Then I realised that this was exactly the kind of ‘bother’ art lovers who live outside London, are often forced to undertake. I quit my grumbling and found my seat.

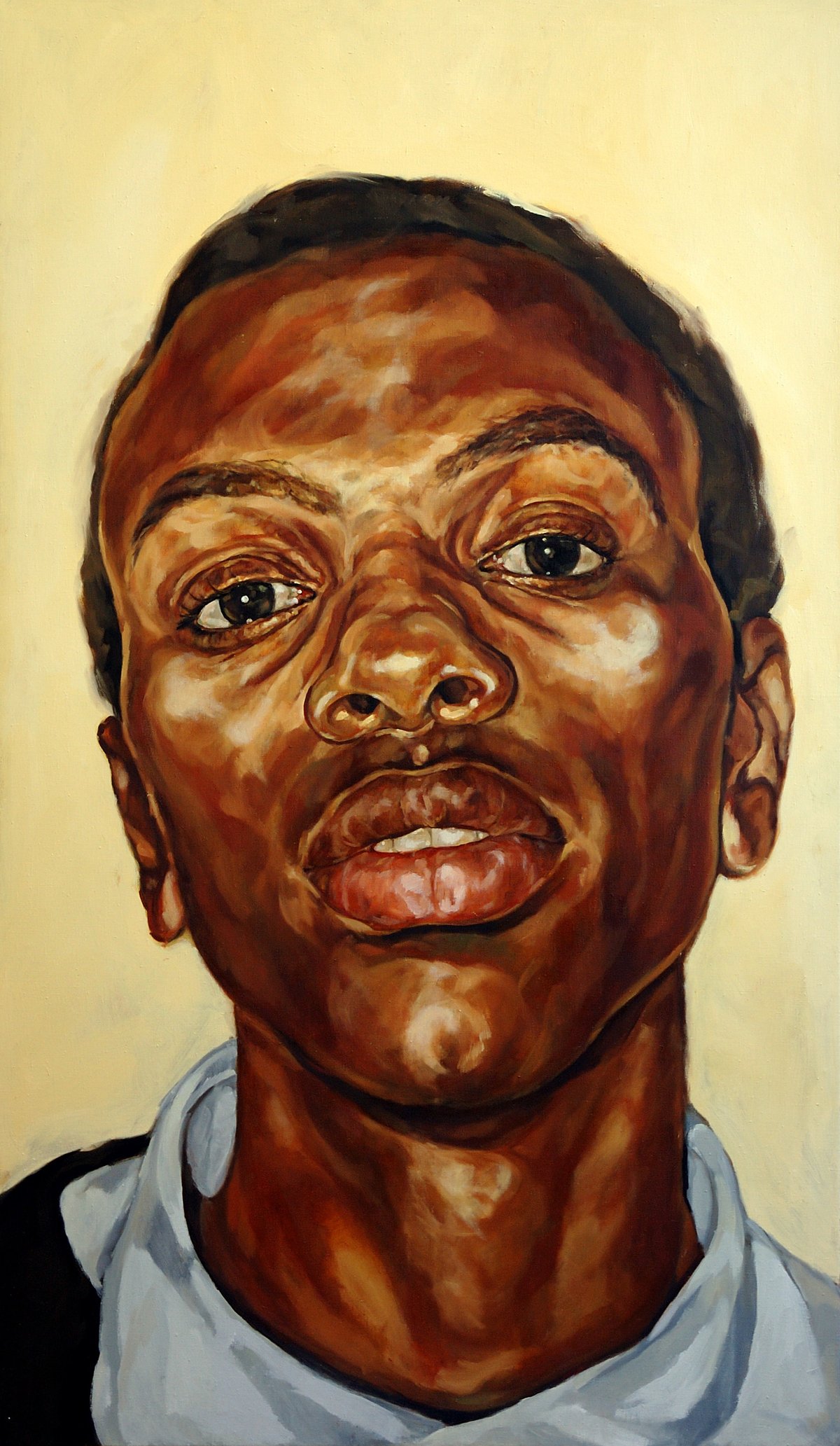

A few hours later, I arrived at the Whitworth, a grand redbrick building with a pillared entrance. I was struck by the giant poster advertising Walker’s show. It was a painting of a Black man’s face, done in startling detail. Walker’s attention to her subject’s facial anatomy was reminiscent of Leonardo Da Vinci. You could see the outline of his nasal cartilage, the hollow of his chin and the texture of his skin in every brushstroke. His gaze was curious or confrontational, depending on what you read into the direct look of a Black man. I hurried into the exhibition to see more.

Barbara Walker, The Sitter (2002) © Barbara Walker. DACS/Artimage 2024. Photo: Gary Kirkham 2024

Walker began her career painting portraits. She was concerned by the negative media imagery of Black people at the time, and so she created her own cannon of images from her friends, family and community. In her early works, Walker’s gaze is tender but not sentimental. Most of her subjects do not face the viewer. Instead, they go about their business, living their lives, unbothered by what you think of them.

I was particularly drawn to Walker’s narrative paintings of Black communal life. In one untitled painting two ‘aunties’ chat, while laden with the plastic carrier bags that aunties always seem to be laden with. In another, a group of senior citizens sit around a table playing dominoes, absorbed in their game. With her precise brush strokes, she had faithfully recorded the talismans and rituals of Black British culture.

Barbara Walker, Vanishing Point 3 (Van den Eeckhout) (2018) © Barbara Walker. DACS/Artimage 2024. Photo: Chris Keenan 2024

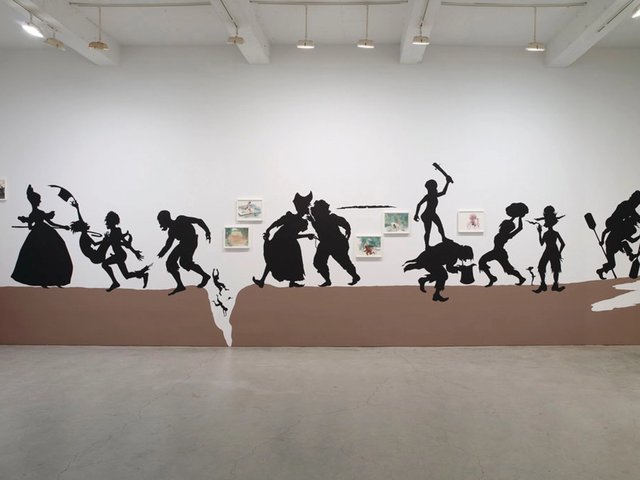

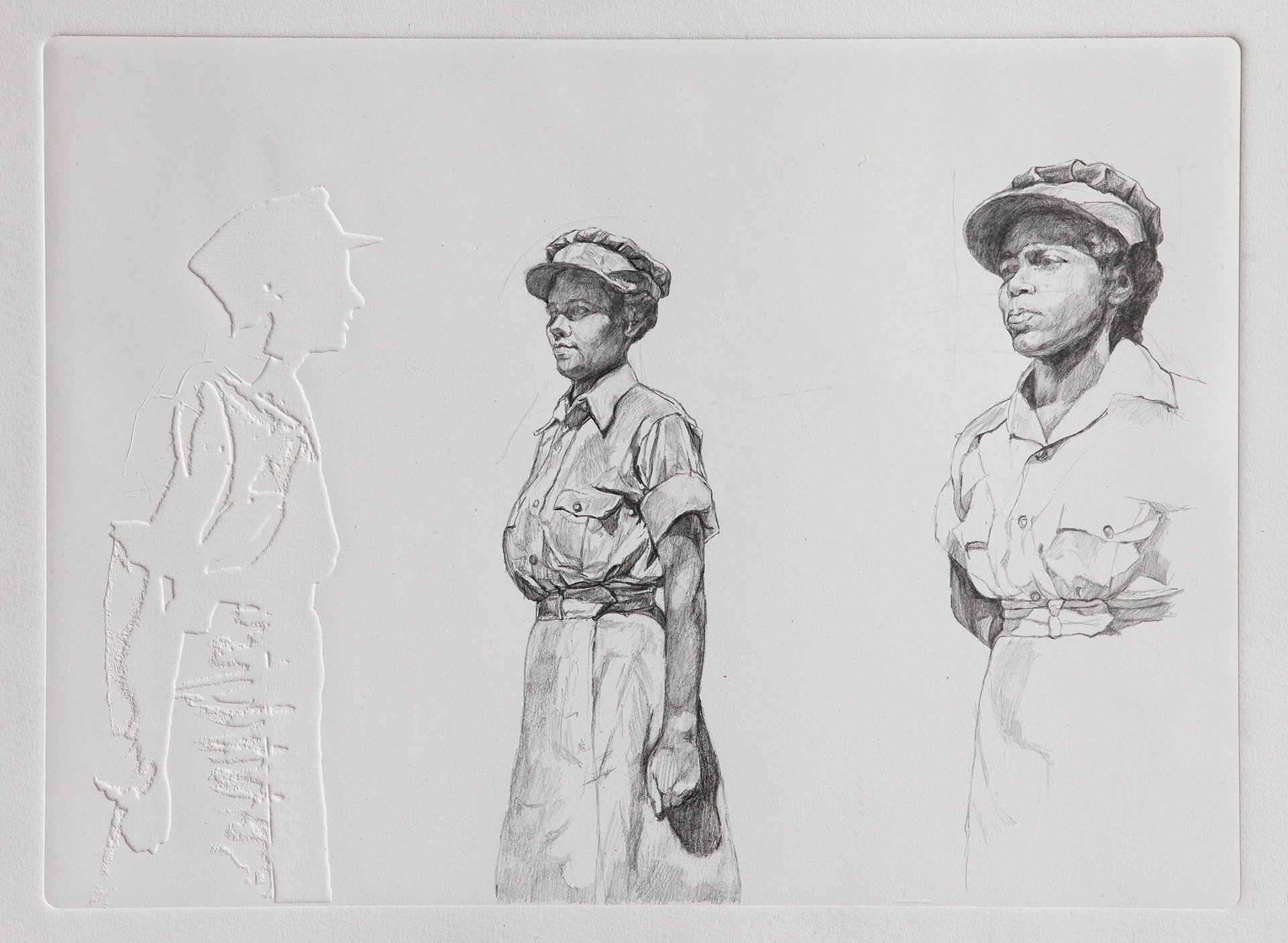

Next to this room, was a selection of work from Walker’s ongoing series, Vanishing Point. Although her focus on the Black figure remained, the work in this room was a radical departure from her earlier work. Firstly, she had exchanged oil and canvas for graphite and paper. Next, she’d turned her keen gaze on Western art history. On noticing that several ‘Old Master paintings’ left Black figures on the margins, she decided to confront this imbalance.

In her reproductions of these famous paintings, the white European figure was erased to a ghostly outline, and the Black figure was drawn with great detail. The formerly peripheral figure had now become the main character in the story.

Was this artistic retribution? Was this Walker’s way of confronting the white gaze and saying, ‘Ah-ha! How do you like to be erased?’ Or was it an invitation to discussion and empathy? How does it feel to be erased? And for the Black viewer, ‘How does it feel to be centred?” Which led to the follow up question of, Did Black people want to be centred in this way?

As I moved between the two rooms, I asked myself, is it more radical for Black people to fight for representation in hostile spaces, to insist that our contributions not be erased from British history, to trumpet that we fought in both World Wars, and we staffed the NHS, and we will not be forgotten? Or is it more radical for Black people to create our own spaces where we are the natural centre of the narrative and we don’t need to fight for attention?

Barbara Walker, Parade III (2017) © Barbara Walker. DACS/Artimage 2024. Photo: Chris Keenan 2024

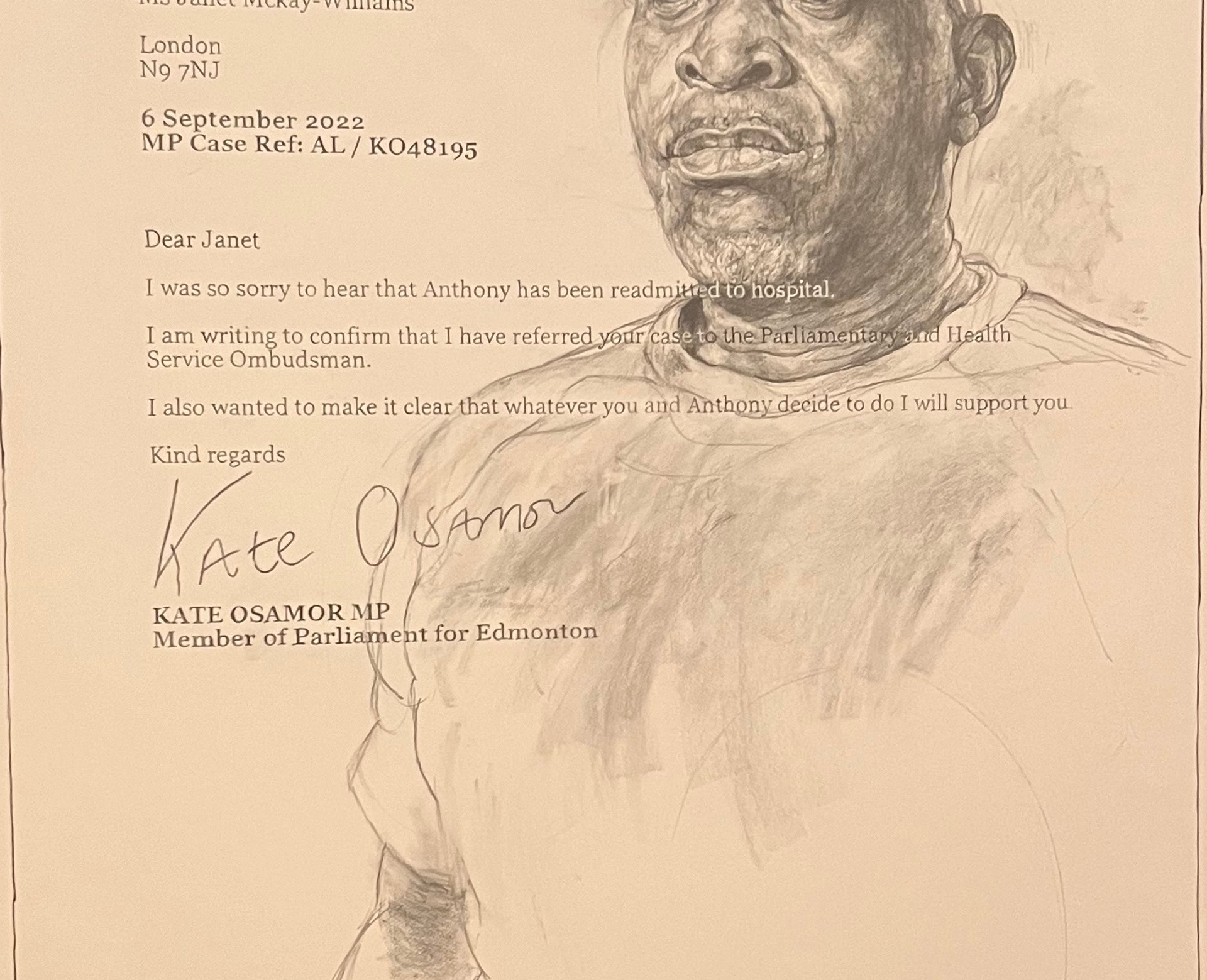

The last room in Walker’s survey offers me an answer. In her Turner Prize-nominated series Burden of Proof, which addresses the Windrush Scandal, Walker is at her most overtly political. On official documents, she draws portraits of migrants of the Windrush generation who were wrongly labelled as ‘illegal immigrants’ by the Home Office.

Barbara Walker, Burden of Proof 5 (2022)

As I studied these works, I decided that as comfortable and comforting as Black spaces are, there was also value in insisting that wider society recognised our contributions. Refusing to engage with a mostly white officialdom, did not mean that this officialdom would not engage with you.

I left Walker’s show with a lot to think about. Firstly, figurative painting is not a dead end for artists, particularly Black artists painting the Black figure. There is still so much to say and so much to capture. There are literally centuries of erasure to redress. As I walked out of the Whitworth, I also felt proud to be Black British. We’re here and we’re not leaving.