Christine Berry and Martha Campbell launched their New York gallery Berry Campbell by searching through grandchildren’s attics and reaching far under widowers’ beds. This was 11 years ago, when the market for overlooked US Abstract Expressionists had not yet been crowded by blue-chip galleries and fairs such as Independent 20th Century and Frieze Masters. Back then, dedicating a roster to relatively obscure, mostly female artists was still a risky business proposition.

Berry and Campbell met while working at a 60-year-old gallery in Midtown Manhattan. Their mutual fascination for post-war American painting led to them signing a street-level lease in the old-guard Chelsea district, opposite Gagosian. After looking at what Campbell describes as “C- or D-list 20th-century male painters” to build a roster, the duo turned to the Archives of American Art. From there, they researched group shows in the era’s most influential galleries, like Betty Parsons, and circled unfamiliar names. Then they made cold calls to family members and estate-holders listed on poorly kept records. Sometimes they were granted the opportunity to dig through piles of paintings at storage units. “We would inform people who knew nothing about art that their mother was friends with Arshile Gorky and participated in exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).”

Perseverance pays off

Their inaugural exhibition, a “museum-quality” show of Charlotte Park, was poorly attended, Campbell says. “We were screaming into the darkness, but we trusted the project and had to remain steady.” Their perseverance is paying off: the meteoric market interest for unsung post-war heroines in the last few years has changed the gallery’s trajectory, bringing six-figure sales, glowing reviews and participation in important fairs like Art Basel and Frieze. “We are being rewarded for the groundwork that we have laid,” Campbell says.

The gallery’s focus on works by overlooked female artists has been an organic transformation. “We didn’t start with the mission of primarily representing women artists; we set out to show good paintings,” Campbell says. “The good paintings happened to be by women.” When they saw Yvonne Thomas’s name in a group show with Pollock and De Kooning, for example, they took the next step of evaluating Thomas’s overall oeuvre. “Most dealers stopped when they saw a single $500 auction record, but, then, record-keeping was insufficient, especially for women artists’ work,” Berry says.

Booster effect

Last month, Berry Campbell closed a successful show of the Asian-American artist Bernice Bing, who died in 1998. This was Bing’s first New York solo show. It followed the gallery’s sale of her 1961 painting Velazquez Family No. II in the group show West Coast Women of Abstract Expressionism in the summer of 2023 for around $400,000 (Bing’s works are usually sold in the range of $30,000). The highest price tag in Bing’s solo show, from which many works were placed with institutions, was $850,000.

Several other artists on the gallery’s roster have seen similar boosts: an Alice Baber painting sold for around $3,000 a decade ago; the artist’s record is now $700,000. Mounting a Lynne Drexler show in 2022 helped put the artist’s legacy back into the spotlight and raise her auction record to more than $1m; White Cube recently sealed a deal with Berry Campbell to co-represent the estate.

The two dealers, who come from art history backgrounds, follow “a conscious formula” that includes a strict selection process: “We will not show an artist unless they were good from the beginning until the end,” Berry says, adding that there must be “enough inventory to build an interest”. The process must be “slow and steady and not fall into the trend of blowing up a market”, Campbell says. This strategy avoids “shortcuts, and always maintains the data to back up a value rise”.

Fair exposure builds business

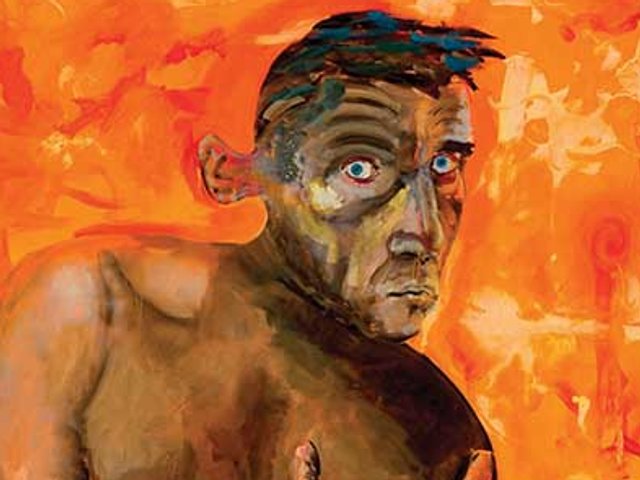

The welcome from top international fairs has helped the global visibility of the gallery’s strictly American roster. After its Frieze Masters debut last year with a solo stand of Ethel Schwabacher, its sophomore outing at the fair last month was dedicated to one of the programme’s few male artists, Frederick J. Brown. The presentation followed the gallery’s 2021 solo show for the 1960s Black figurative painter, which was organised by the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s first Black curator, Lowery Stokes Sims.

Berry believes the gallery has the responsibility to tell their artists’ “fascinating background stories”. Brown was among the first Black artists to show at a blue-chip gallery, in the early 1980s. For its first participation in Art Basel Miami Beach’s main section this year, Berry Campbell will show a group presentation of key post-war female players, including a 4.4m-wide painting by Baber. It has recently received the green light for Art Basel Hong Kong, where it will exhibit Bing, alongside Emiko Nakano and Elizabeth Osborne.

A main indicator of success can be seen in the gallery representing a quarter of the artists that were featured in the Denver Art Museum’s seminal Women of Abstract Expressionism exhibition in 2016. “Many collectors and institutions opened up their minds and realised they were missing out on many names,” Berry says. The dealers delved into Bing’s work after seeing her work in the Denver show’s catalogue. “Many of our colleagues said kudos for getting her work because there were rumours that the estate was empty,” Campbell says. And how did they get hold of the inventory? “We just did the homework and kept making the phone calls.”