With an exhibition opening today at the Serpentine Gallery and commercial shows at Max Hetzler and Lévy Gorvy galleries, the German artist Albert Oehlen is the toast of London this week.

To coincide, Gagosian has an exhibition of new paintings in Hong Kong, while Skarstedt gallery in New York is showing canvases from Oehlen’s 1990s Fn series.

Variously described as “the most resourceful abstract painter alive”, “pictorially excessive” and having a “dandyist aesthetic”, Oehlen has reinvented himself tirelessly over his 40-year career. He has produced numerous series that incorporate, among other approaches and materials, Abstract Expressionist brushstrokes, graffiti, computer-generated elements and textiles. His Bad and Computer paintings are among his best-known.

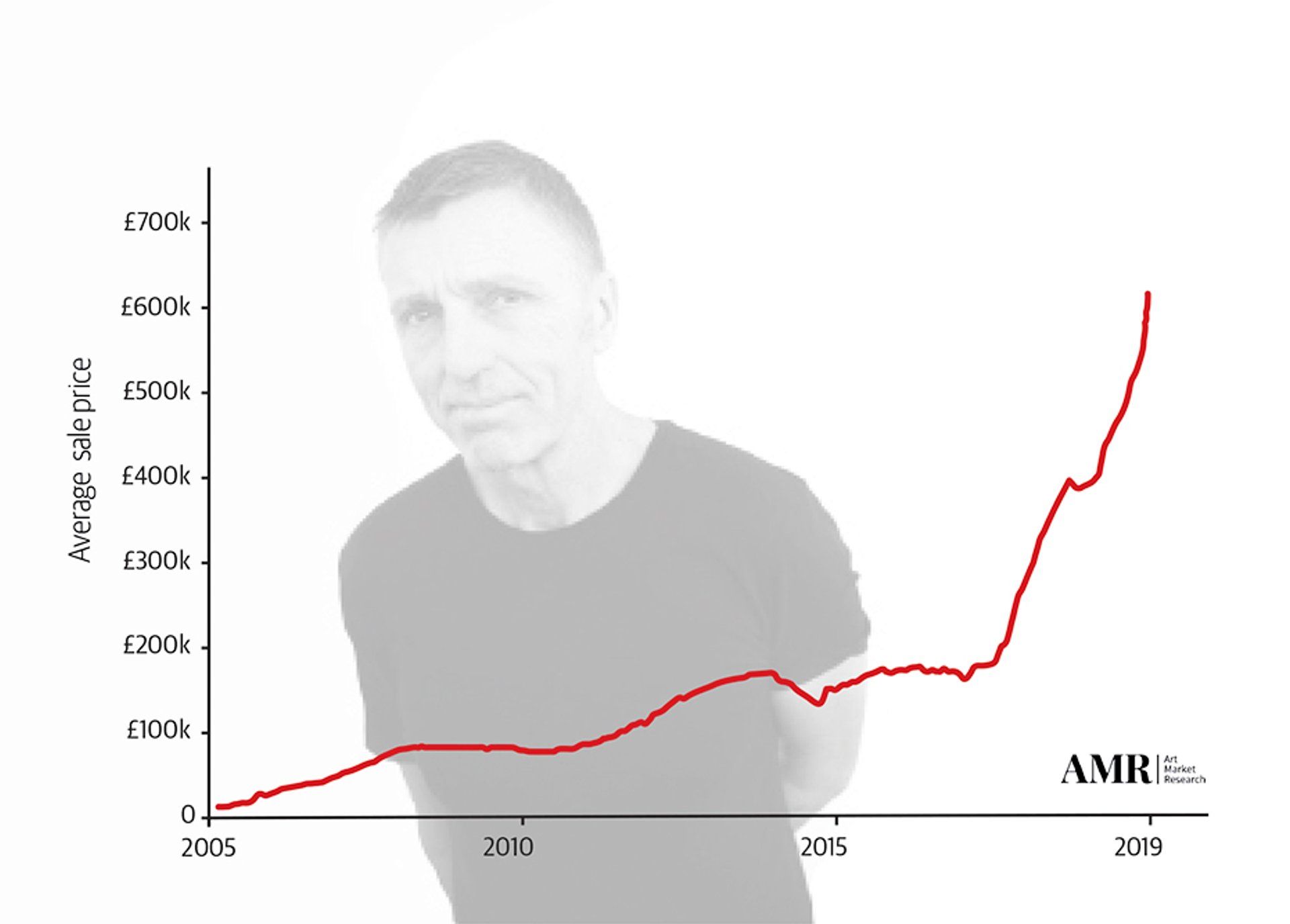

Auction data gathered by Art Market Research shows a 5,500% growth in the average value of Oeheln’s paintings since 2005.

Prices

Oehlen has benefited from institutional support for several decades, with a long list of museum shows across Europe and, increasingly, the US—and now the UK. His market is catching up accordingly.

Price charts compiled by Art Market Research show a hefty 5,500% hike in the average value of his paintings since 2005, and a 190% rise since October 2016 alone when his prices first broke the £1m barrier at auction.

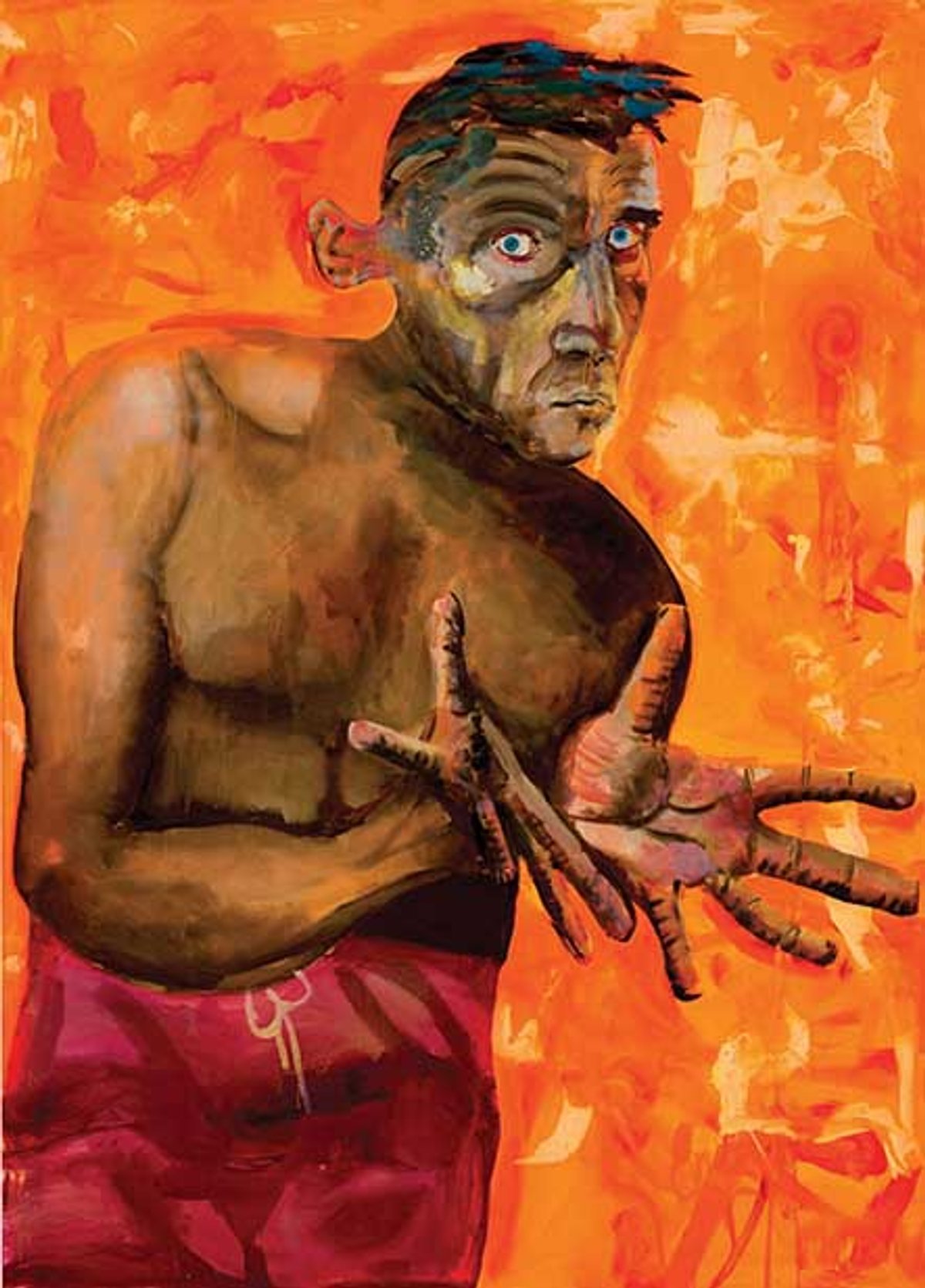

Oehlen’s auction record stands at £6.2m ($7.9m), achieved in June at Sotheby’s, London for a rare 1998 self-portrait from the collection of the German writer and theorist Harald Falckenberg, which was bought by secondary market dealer Per Skarstedt. The auction house is among those supporting Oehlen’s Serpentine show and has two paintings on the block this week.

Having studied under Sigmar Polke, Oehlen is part of a new wave of German Expressionists, which includes Martin Kippenberger and Werner Büttner. Of the younger generation, “Oehlen is the one who stands out the most right now; he is the one everyone is very confident about,” says Sotheby’s senior director Martin Klosterfelde, noting that he has made a private sale on a par with Oehlen’s auction record.

Gerhard Richter is widely regarded as the world’s most important living painter (Richter’s record stands at £35.8m/$46.3m), so could Oehlen reach his giddy heights? Klosterfelde thinks so. “Once an artist reaches the $5m mark, they usually go on to a much higher level,” he says.

In the gallery’s virtual viewing room in March, Gagosian sold a large untitled abstract work from 1988 for $6m, just two hours after it was unveiled online ahead of Art Basel in Hong Kong (it did not go to an Asian buyer, according to the gallery). In an unusual bid for transparency, Gagosian provided analysis of the artist’s market. For example, in 2008, 53 works by Oehlen came up at auction and sales totalled just under $5m. In 2018, 30 came up and made around $24m.

Gallery support

There is a groundswell of gallery support for Oehlen. Max Hetzler has been his long-time primary market dealer, and is currently showing Oehlen’s early Spiegelbilder, or Mirror Paintings (1982-90), while Gagosian has represented him since 2011. In his final exhibition at Thomas Dane in October 2011, five works were sold for between €175,000 and €285,000.

Skarstedt Gallery and Lévy Gorvy are active on the secondary market and have experience of organising important historical shows. At Art Basel in June, Skarstedt sold Rasieren (2005), an oil and paper on canvas, with an asking price of $2.5m. In London, Lévy Gorvy is currently showing Oehlen’s only installation piece, from 2005—a replica of the artist’s bedroom with yellow wallpaper, potted plant and vinyl records. The artist appears as a painted self-portrait tucked under the bed covers.

Ingwertopf (Ginger Pot) (2000) is due to go on the block at Sotheby’s on 3 October (est. £800,000-£1.2m) © Albert Oehlen. All Rights Reserved; DACS 2019

Collectors

Since taking him on in 2011, Gagosian has worked to build Oehlen’s US market, according to gallery director Stefan Ratibor. “We’ve been quite successful,” he says.

Meanwhile, the gallery’s Hong Kong show of 11 new abstract watercolours on canvas sold out before it opened on 12 September, all to Asian collectors. Works had an asking price of €1.3m each.

Victoria Gelfand-Magalhaes, Lévy Gorvy’s European president, believes Oehlen’s market is about to move up a notch. She says: “It’s the Europeans who are often the first to appreciate an artist, but it takes Americans to start buying for the market to explode. And now with Asia coming in, we’re at that tipping point.”

The luxury goods billionaire François Pinault is one high-profile buyer, and the Norwegian investor Christen Sveaas is also known to own a number of works, while a 2006 abstract from the collection of the late US radio and cable investor James Rich sold for £1.8m in the same June sale that Oehlen’s auction record was made.

Pitfalls

The varied nature of Oehlen’s work can be difficult for new collectors to navigate. “It takes a bit of a sophisticated buyer to really wrap your head around all the different bodies of work because the minute you’ve got it, he moves on,” Gelfand-Magalhaes says. “That’s very exciting, but for somebody new to the market, it’s not always obvious.”

Oehlen does not have a catalogue raisonné (curators and dealers say this goes against his constant reinvention), although, according to a comprehensive monograph published by Taschen, he has produced more than 400 paintings since the late 1970s.

Albert Oehlen, Portrait (2012) Courtesy Gagosian Gallery, Photo by Oliver Schultz-Berndt

Critics' View

Like Marmite, Oehlen divides opinion. Hans Ulrich Obrist of the Serpentine Galleries, says the artist reflects this very division in his work: “Oehlen’s interest in so-called ‘bad painting’ focuses specifically on this notion of taste, allowing a certain crudeness of style and subject matter to enter the field. His conscious playing with these categories is perhaps why people’s views can be so far-reaching-—he continuously challenges, expands and blurs the boundaries of what we consider ‘good’ or ‘bad’ painting. It’s the diversity of Oehlen’s approach that makes him one of the most original and inventive painters of our time.”

Ben Luke, the contemporary art critic at the Evening Standard and Review editor at The Art Newspaper, is not convinced. He says: “In an interview with the Guardian in 2016, Oehlen said about his experimental approach to painting: ‘If we were talking musically, it’s definitely Frank Zappa, not Leonard Cohen.’ And that sums up what I find most difficult about his work: I can be amused and engaged up to a point by the playfulness, the stylistic leaps and knowing nods, but I can never go beyond that to being enthralled or moved. And that’s what I want painting to do.”