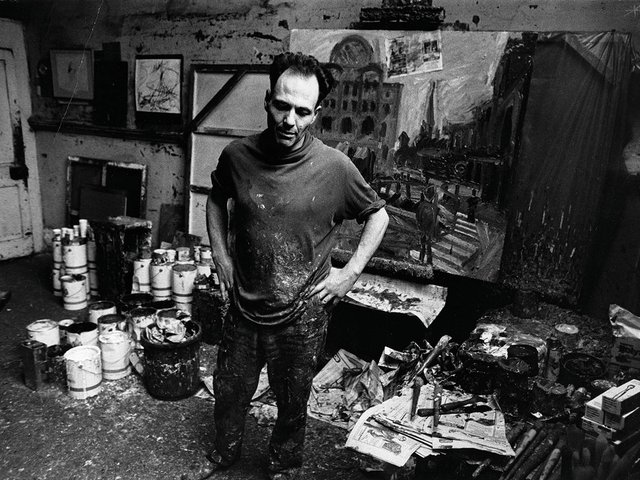

Following the death of the artist Frank Auerbach, one of the leading painters of the post-Second World War generation, at the age of 93, the art world has paid tribute to the quality of his work, his encyclopaedic knowledge of art history, and his personal charm and wit.

To Colin Wiggins, who curated Frank Auerbach and the National Gallery: Working After the Masters (1995), at London’s National Gallery, Auerbach is an artist whose work will—like that of Francis Bacon and Paula Rego before him—be lifted “into another dimension” by posterity. “The work is titanic, utterly sublime and wonderful,” Wiggins tells The Art Newspaper. “Like Picasso, everything he touched was wonderful. They are just magisterial things. And I've got no doubt that they're going to last the course and be seen as one of the key achievements of post-war painting.”

Francis Outred—the gallerist and former head of post-war and contemporary art in Europe at Christie’s, who is staging a London show of Auerbach’s landscapes until 7 December with Offer Waterman—writes on Instagram of Auerbach as “a humble giant of figurative painting” whose “passing signals the end of an era.”

“It has been quite strange to be sitting in our exhibition these past couple of days,” Outred writes. “The paintings, which have so much vitality and such an urgency to reconfirm lived existence, created by an artist who has just left us. Whilst their surfaces record fleeting moments in time, they carry within their layers an archaeology of lived experience; it is hard to believe this will no longer continue.”

Referring to the exhibition—which includes one of the artist’s favourite paintings Primrose Hill, Hot Summer Evening (1974-75), not seen in public for 50 years—Outred says: “Whether it be Regent's Park or Hampstead Heath, both of which he painted only once, or Primrose Hill which he painted over 40 times between 1954 and 1987, these are places which speak to the history of the city and whose presence provide not just a source of comfort but also a connection back to our past. They have remained relatively unchanged over centuries, yet Auerbach felt the need to return again and again. Whilst he is no longer with us, his paintings and his incredible musings on painting will continue to live on and inspire many generations to come.”

To the art historian Matthew Holman, writing in his obituary of Auerbach for The Art Newspaper, the German-born London-based artist “might have wished only for having done one thing—to paint, and to go on painting—but he far exceeded the modest benchmark he set himself... Auerbach was called by the Muse to take his place among these disparate outsiders on the margins, as well as his Old Master heroes in the decorated halls of art history. He will be remembered as an irrepressible light in both rooms, and as a dedicated artist whose contribution to portraiture and landscape painting has had no equal during his long lifetime.”

The National Gallery, London, posting on X, said “We are saddened to learn of the death of … Frank Auerbach. Auerbach regularly visited the Gallery to sketch works in our collection while he was a student. He went on to produce hundreds of drawings based on National Gallery works, a selection of which were shown in our 1995 exhibition, Frank Auberach and the National Gallery: Working After the Masters.” The gallery also provided a link to a webpage highlighting “the close relationship” it had to Auerbach.

We are saddened to learn of the death of artist Frank Auerbach.

— National Gallery (@NationalGallery) November 12, 2024

Auerbach regularly visited the Gallery to sketch works in our collection while he was a student. He went on to produce hundreds of drawings based on National Gallery works, a selection of which were shown in our… pic.twitter.com/qeKtlXe7dz

To Waldemar Januszczak, the chief art critic of the Sunday Times, writing on X, Auerbach’s “messy, heartfelt, embroiling art worked at a slower pace than modern life and stuck to your memory like mud.”

I’ve been filming in Japan so I missed the death of Frank Auerbach. So sad. A huge loss. His messy, heartfelt, embroiling art worked at a slower pace than modern life and stuck to your memory like mud. It was always there. Now it isn’t. Nice obit: https://t.co/6wdFpkQNTq

— WALDEMAR JANUSZCZAK (@JANUSZCZAK) November 12, 2024

Wiggins says he found Auerbach, from their first meeting in the mid-1970s, to be “joyously lighthearted and great fun to be with, which goes against all received ideas about him.”

“He was just very funny,” Wiggins says, with “a wonderful sense of comedy and a profound knowledge of English music hall comedians. He knew every single Rubens painting, every single Rembrandt painting, every single Titian, Velasquez… but he also knew jokes by Ken Dodd and Max Miller.” When Wiggins and Auerbach were making a film to go with the 1995 exhibition at the National Gallery, Wiggins remembers: “We sat down while the technicians were kind of loading up in front of [the British artist J. M. W] Turner's Dido Building Carthage. And he started comparing this painting to a Max Miller stand-up routine.... He saw Max Miller. He used to go to the music halls in the late 1940s.” When Wiggins asked him about the comparison between Miller’s and Turner’s work, Auerbach answered: “Well, it looks so easily achieved. This picture, it looks as if Turner has just conjured up the whole thing from out of his sleeve with no preparation and no thought. He just stands in front of the picture. It just happens. Which of course it doesn't. But when you watch Max Miller, it's the same. You think, how does he do it? One gag after another from out of his sleeve, as if there hasn't been months and years of practice to get that good.”

The institution Tate, writing on X, quoted Auerbach: “Painting is the most marvellous activity humans have invented...”. The gallery continued: “We are deeply saddened to hear that Frank Auerbach has died. Auerbach’s paintings have been described as some of the most resonant, inventive and perpetually alive works of art of the 20th and 21st centuries. Since his early works, his intentions have been consistent: ‘To record the life that seemed to me to be passionate and exciting and disappearing all the time’.”

Painting is the most marvellous activity humans have invented’ – Frank Auerbach

— Tate (@Tate) November 12, 2024

We are deeply saddened to hear that Frank Auerbach has died. Auerbach’s paintings have been described as some of the most resonant, inventive and perpetually alive works of art of the twentieth and… pic.twitter.com/T1WeDR5v0j

The Courtauld Institute of Art, London, posted that it was “deeply saddened to learn of the death of Frank Auerbach… We were honoured to stage a major exhibition of his earlier work earlier this year, where he also recorded a rare interview reflecting on his life and artistic legacy.”

We are deeply saddened to learn of the death of Frank Auerbach (1931-2024).

— The Courtauld (@TheCourtauld) November 12, 2024

We were honoured to stage a major exhibition of his earlier work earlier this year, where he also recorded a rare interview reflecting on his life and artistic legacy. https://t.co/OKtl4a1sZp pic.twitter.com/KJqyhBS31Y

For the art historian Richard Morris “Frank Auerbach will be remembered as one of the major draughtsmen of his age. He was the master of the hard-won image; he drew his sitters over and over again, erasing the image after each session so that only an outline remained and repeated the process until he felt he had captured the person’s essence. This is a self-portrait from 1958.”

Frank Auerbach (whose death was announced this morning) will be remembered as one of the major draughtsman of his age. He was the master of the hard-won image; he drew his sitters over and over again, erasing the image after each session so that only an outline remained and… pic.twitter.com/HxK82e6AyT

— Richard Morris (@ahistoryinart) November 12, 2024

The writer Sara Wheeler remembered that “For many years in the late 1980s/90s I lived in Mornington Crescent and if I went out at 7am I would often see Frank Auerbach on the corner, painting. It lifted my heart as I knew I was watching a genius at his work.”

For many years in the late 80s/90s I lived in Mornington Crescent and if I went out at 7 am I would often see Frank Auerbach on the corner, painting. It lifted my heart as I knew I was watching a genius at his work. RiP. pic.twitter.com/m07LVSFwBQ

— Sara Wheeler (@saradwheeler) November 12, 2024

Auerbach: Portraits of London, Offer Waterman and Francis Outred, 17 St George Street, London W1, until 7 December