Frank Auerbach did not think very often about how he would be remembered. “When I was young, when I started, I thought like everyone else that the aim was to become marvellous and to be famous, which has totally fallen away by now,” he reflected in an interview with the BBC earlier this year. “I live a quite amazingly restrictive life, and I just go on in this very quiet way; if I hadn’t been forced by this interview to make these presumptuous and pretentious statements, I would have been innocently sloshing away in the room next door [with the knowledge that] the pleasure and the success is in the feeling of having done something.”

Auerbach was the truthful cliché of the painter’s painter who continued to paint, with limited interruptions, for eight-tenths of a century. He managed to be that rare thing: the artist who stood outside of the clatter of his own moment and yet produced some of the most enduring and perceptive observations of what it meant to be alive during his time.

Auerbach was born in Berlin in 1931, the only child of older Jewish parents, Max, a patent lawyer, and Charlotte, an art student from Lithuania. He spent the first few years of his life in Wilmersdorf, a middle-class district of Berlin. After Hitler’s ascent to power, the Auerbachs arranged for their seven-year-old son to move to England; Charlotte stitched a red cross on the larger items in his suitcase to indicate they were for when he had grown up, and two crosses for sheets and tablecloths, for when he would marry. Auerbach’s safe passage to London was secured not by the Kindertransport, the co-ordinated rescue effort that brought nearly 10,000 mostly Jewish children from Nazi-controlled European territories, but the beneficence of Iris Origo, the celebrated Italy-based Anglo-American author.

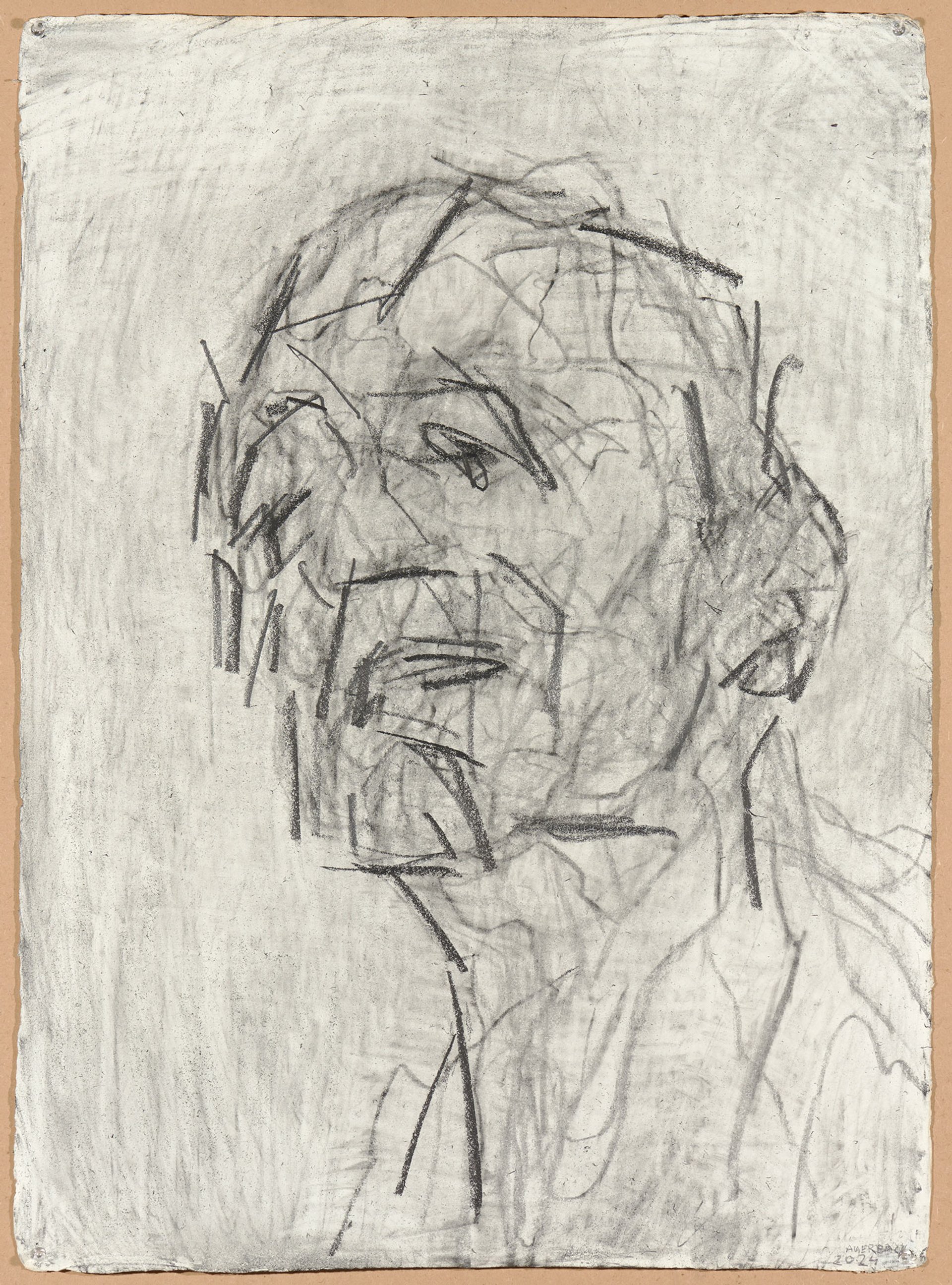

Frank Auerbach, Self Portrait (2024) in graphite on paper Photo © Andrew Smart, A C Cooper Ltd. Courtesy Frankie Rossi Art Projects

Auerbach was sent to Bunce Court in the sleepy village of Otterden in Kent, a Quaker-led boarding school which he affectionately described as “a little republic”. It was here that he fell in love with British painting and first encountered a black-and-white reproduction in an Arthur Mee children’s encyclopaedia of J.M.W. Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire (1838), which made him want to “do better and be less superficial”. His parents were both killed in a concentration camp in 1942. “[I was] at no point shocked or overwhelmed,” he reflected much later, “[when] it was gradually leaked to me [that] they’d been killed, taken to a camp and killed. I don’t know which one, Auschwitz probably.”

After Bunce Court, Auerbach moved to London, where he was supported by his much older cousin Gerda Boehm, who would become an important muse, and the subject of many of his early Charcoal Heads, which were displayed together at the Courtauld Gallery earlier this year.

The influence of David Bomberg

Auerbach enrolled in art classes at the Hampstead Garden Suburb Institute and even took up acting, playing roles in Peter Ustinov’s play The House of Regrets and in productions at the radical 20th Century Theatre in Westbourne Grove. But it was painting that kept calling him back. After spending hours trawling to the entrances of the capital’s art schools with his portfolio under his arm, Auerbach was accepted at St Martin’s College and the Borough Polytechnic Institute, where the kindly principal, Mr Patrick, put together a timetable for him: “I think I’ll put you in for a day with David Bomberg,” as if to say, “Well, Bomberg’s a bit dicey, but you never know—you might get on with him.” The ageing Vorticist Bomberg was indeed dicey, and master and apprentice often clashed in life classes in the old engineering rooms, but the traces of Bomberg’s early influence—his hard-edged lines for the human form, his outsider’s observations of British life—can be tracked throughout Auerbach’s practice.

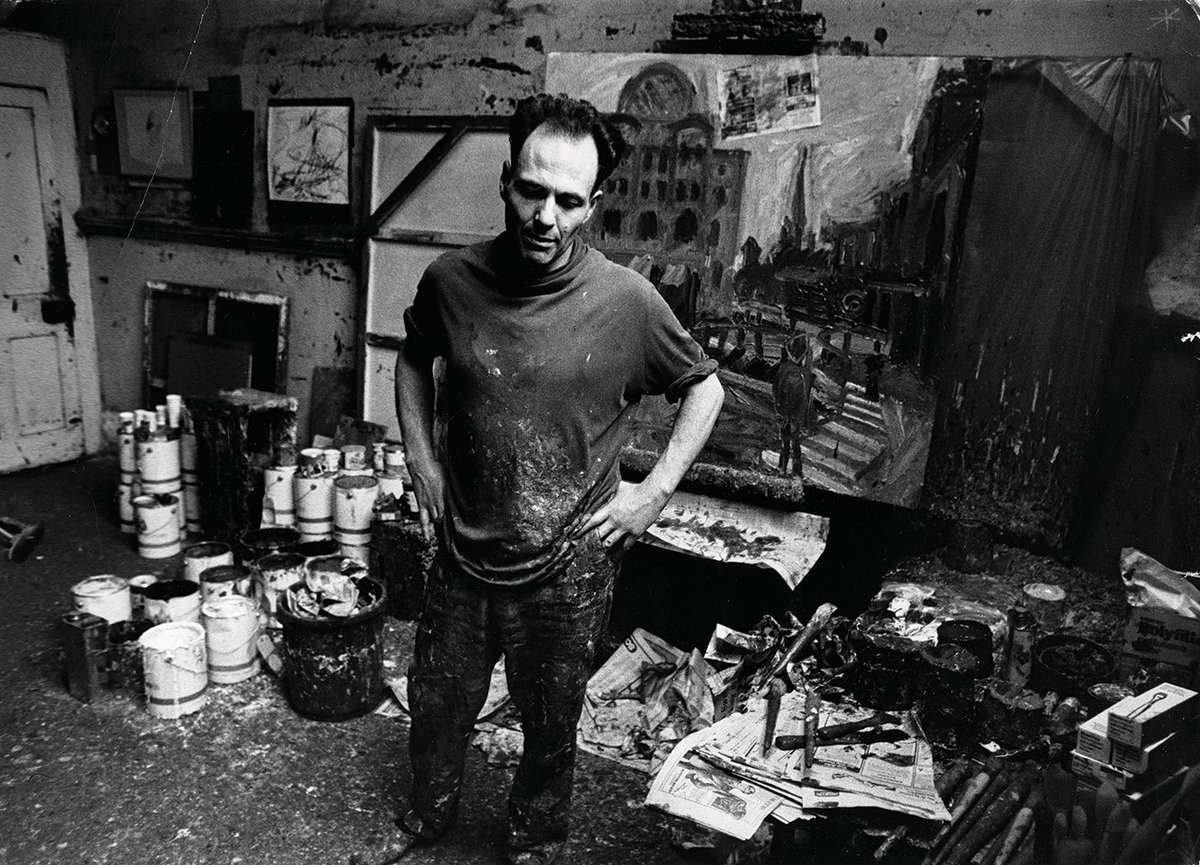

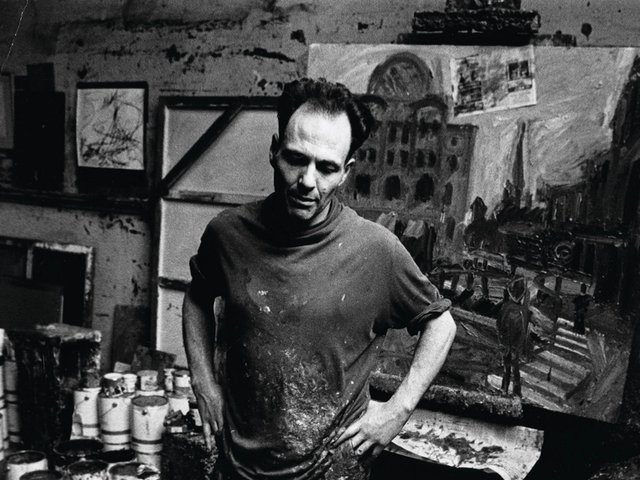

Frank Auerbach Photo by David Dawson

Auerbach’s breakthrough came in the summer of 1952, when he made two formative paintings. E.O.W. Nude, which depicts Estella Olive West, whom he described as his greatest influence, during a fraught sitting in which he found in himself “enough courage to repaint the whole thing, from top to bottom, irrationally and instinctively”. Ultimately, after entirely reworking the canvas, “I found I’d got a picture of her.”

The second epiphanic painting came once he had got a place to continue his studies at the Royal College of Art (1952-55). During a “crisis” of over-confidence as he felt under the cosh to conform to the college’s conservative demands, Auerbach turned on his heel and looked out to the excavations reaching down and the scaffolding reaching up on a cavernous building-site on the Earl’s Court Road. Give or take, it would be his heavily worked and reworked portraits of female sitters, as well as the frenetic urban activity of a transforming London that defined his contributions to the British figurative tradition. From then on, he seldom sought subjects from anywhere else.

A monastic life

After his breakthrough, Auerbach wanted to spend every moment in the studio. He sought out and committed to a monastic life. He invariably went to bed by nine and was up at five, if not before. “Mondrian didn’t have a life,” he reassured himself: to be an artist was a decision, and to deny social demands and domestic considerations was essential. For more than half a century, from his final year at the Royal College, where he graduated with the silver medal, Auerbach lived in a studio down an alley behind Mornington Crescent in Camden.

Auerbach's studio Photograph Geoffrey Parton. Courtesy Frankie Rossi Projects

At just 20ft by 20ft, the studio provided Auerbach with just enough space to work on two genres simultaneously. But this is not to say Auerbach did not get out. The city of London itself continued to be his best-loved subject. He was restlessly inspired by its Blitzed ruins, with its hollowed-out houses and its eviscerated grandeur. “London looked marvellous,” Auerbach recalled of his early years in the city: “Like the chalk pits on the Downs, caverns and holes. Marvellous: a mountain landscape.” He made photo essays of the meat porters shouldering carcasses in Smithfield Market with blood on their white aprons. He wandered around Soho at night. Early years of penury prompted him to paint almost entirely in earth colours from five-litre cans. “It is what my life was like,” he reflected, “walking around ruined London and having intense relationships with a few people.”

One of those few people, Julia Wolstenholme, who was a year below Auerbach at the Royal College, started sitting for him in 1959 and continued to do so until the end of his life. They married, had a son called Jake, a film-maker, but soon drifted apart. Auerbach’s claim that he thought of “painting as something that happens to a man working in a room, alone with his actions, his ideas, and perhaps his model” was unconducive to happily married life, but a deeper respect maintained their bond. Wolstenholme compared the experience of sitting for her estranged husband as akin to “washing up”: something that was (like it or not) necessary and takes more time that you might want it to on mid-week evenings and slow weekend afternoons. Juliet Yardley Mills (or J.Y.M.) would soon become a favoured model after she met Auerbach at Sidcup Art School in the 1950s. These fleshy, Soutine-inflected paintings were often called “heads” instead of “portraits”, and often see J.Y.M. at full-tilt as though lost in reverie, with her neck elongated, her eyes transfigured into thin slits, and almost one half of her aspect hidden from view.

No sooner had Catherine Lampert curated a 1978 mid-career retrospective at the Hayward Gallery than she was asked to sit, which she did, on Monday evenings for 25 years, and then Friday afternoons. “For the first few years I was sitting for Frank Auerbach it was hard to reconcile listening to someone so knowledgeable, so gifted at expressing his thoughts and memories, with the person who spent nearly all his time concentrating his whole being on a very messy, physically as well as mentally arduous process that took place in a cramped room.” Lampert went on to curate subsequent retrospectives, with Norman Rosenthal at the Royal Academy of Arts in 2001 and at the Kunstmuseum, Bonn, and at Tate Britain in 2015. “The reward is to get smacked in the face by the terrifying glory of the world Auerbach is stunned by every morning,” wrote Jonathan Jones in a review for The Guardian. “Art, the master reveals, is a work that never ends and an eye that never dulls.”

Frank Auerbach, In the Studio II (2002), oil on board Courtesy Frankie Rossi Art Projects

Auerbach will be remembered as a key part of the much-mythologised generation of the School of London, an outcast band of predominantly non-Londoners who found in the grit and grime of their adopted city enough material to invigorate a national ambition for Modernist painting. They winced away from the contemporary vogues for pure abstraction and minimalism and re-embraced the figure. Auerbach was for a long time particularly close to Leon Kossoff, with whom he shared a passion for channelling ravines of impasto; saw the gregarious Francis Bacon twice a week for 15 years; and drew the rare praise of his fellow Berliner-Jewish refugee Lucian Freud, who wrote: “Prompted more by exuberance and love of great works of art than a need for reinforcement, Frank Auerbach uses past paintings to vary and extend his obsessive subject matter.” Auerbach described these sparring yet generative relationships like being a boxer “in the ring with them, as Hemingway used to say”.

An affinity with Old Masters

Against himself, though, Freud was right. Auerbach was always more at home with Rembrandts, Titians and Rubens, his companions on perpetual long walks through the grand rooms at the National Gallery, than he ever was with the artists of his own time. In 1965 David Wilkie, an insurance clerk in the City, commissioned Auerbach to paint a work based on Titian, which resulted in a series of further works donated to the Tate, including the exquisite Bacchus and Ariadne (1971). Twenty-four years later, the exhibition Frank Auerbach and the National Gallery: Working after the Masters, was built around the drawings he made from paintings in the collection. In 2013-14, six paintings by Auerbach were displayed alongside several Rembrandts at Ordovas, London, and then at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Auerbach might have wished only for having done one thing—to paint, and to go on painting—but he far exceeded the modest benchmark he set himself. In the 2024 BBC interview, Auerbach reflected upon how “one of the many mysteries of art is how the Muse picks the most disparate people”, before listing poets from “a hunchback dwarf in Alexander Pope, an illiterate farm labourer in John Clare, or a misfit woman who kills herself by drinking a bottle of disinfectant in Charlotte Mew” but, nevertheless, it is the Muse “who calls them to be great poets”. Despite the obstinate quietude of his life after his childhood tragedies, Auerbach was called by the Muse to take his place among these disparate outsiders on the margins, as well as his Old Master heroes in the decorated halls of art history. He will be remembered as an irrepressible light in both rooms, and as a dedicated artist whose contribution to portraiture and landscape painting has had no equal during his long lifetime.

Frank Auerbach; born Berlin 29 April 1931; married 1958 Julia Wolstenholme (one son); died London 11 November 2024.