In architecture, the private house is at once the most personal and the most emblematic of building types. A creative duet between designer and client crystallises the domestic ideal at a specific moment in time. Art Week Tokyo, with help from Kazuyo Sejima of the Pritzker Prize-winning architects SANAA, is launching a new programme of architecture tours that will offer visitors a rare glimpse inside several post-war private residences around the city. We look here at the lesser-known histories behind them.

The patron saint of Japanese Modernism in architecture is undoubtedly Le Corbusier. Among his influential Japanese disciples, Takamasa Yoshizaka is the least known but the most radical. An avid mountaineer, he designed Villa CouCou (1957) for Hitoshi Kondo, a fellow climber and professor of French literature at Waseda University, after a two-year apprenticeship at Le Corbusier’s Paris atelier. The irregular plan, sweeping roof, canted concrete walls, deep-set coloured windows and robust built-in furniture reflect Yoshizaka’s Corbusian tutelage. “Think on the spot” was his mantra and many details were decided on site. For Yoshizaka, “building” was always understood as a verb rather than a noun.

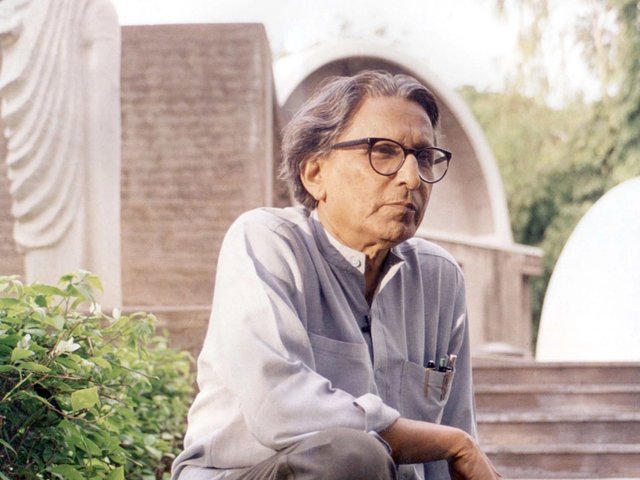

Seiichi Shirai is almost the antithesis of Yoshizaka. A deeply intellectual architect, Shirai studied philosophy in Weimar-era Heidelberg and Berlin before the rise of Nazism forced his return to Japan in 1933. His work eschewed facile innovation, exhibiting a profound sensibility for enduring universals. Shirai saw more clearly than any of his generation the darkness at the heart of modernity. He regarded tradition as “anima”, the shared breath of a living culture, and a truly modern architecture as one that drew sustenance from it. His Atelier No. 7 (1959) outwardly reflects its suburban context, but the dark timber frame, white plaster infill and shoji panels of its interior evoke a historic minka farmhouse of rural Japan.

The Osaka-born architect Takamitsu Azuma built the Tower House (1966) for his young family after moving to Tokyo. One of the most significant Japanese urban houses of the 20th century, it is an extraordinary nugget of architectural intelligence compressed within a tiny 20 sq. m triangular plot left over from the construction boom of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. The severe site constraints stimulated a muscular six-storey form in raw concrete, in which life is organised vertically, each level a room. Rejecting mass housing and suburbia for their abandonment of urban life, Azuma built a dwelling in intimate relationship to the city, on a piece of land as large as he could afford beside the new thoroughfare of Gaien Nishi-dori.

The 1970s was the decade when Japan developed into an affluent consumer society. Toyo Ito was the architectural poet of this shift, whose lightweight, transparent language expressed a postmodern age of information flows and commodified symbols. The House in Hanakoganei (1983) is an early articulation of concerns that would characterise Ito’s work. A steel-framed structure clad in metal and fibre-cement panels, it presents a tight juxtaposition between two distinct volumes: a gable roof and a barrel vault. The latter became the principal motif of Ito’s own residence the following year, its tent-like openness evoking the heady experience of Tokyo in the 1980s “bubble era”.

Lightness and fluidity are qualities that Ito’s celebrated disciple Kazuyo Sejima has helped disseminate into perhaps the most influential expression of Japanese architecture in the 21st century. Art Week Tokyo’s VIP guests will have a chance to enter Sejima’s factory of imagination in the SANAA office, inside a seemingly nondescript warehouse built on reclaimed land beside Tokyo Bay.

• Public architecture tours of Tower House and the House in Hanakoganei will run on 8-9 November; visitsto Atelier No. 7, SANAA office and Villa CouCou are part of Art Week Tokyo’s VIP programme

• Julian Worrall is a professor of architecture and the head of the School of Architecture and Design at the University of Tasmania