After graduating in architecture at Tokyo’s Kogakuin University, Eiko Tomura studied landscape architecture in the US before moving to Paris. Back in Japan, she project-managed Junya Ishigami + associates’ award-winning Art Biotop Water Garden in Nasu, before founding Eiko Tomura Landscape Architects in 2017. A finalist in a competition to develop the Camden Highline in London, the firm is working on projects including Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden revitalisation in Washington, DC, Expo 2025 in Osaka and, now, this year’s AWT Bar in the heart of Minami-Aoyama. Tomura told us about the bar’s careful ambiguity and her wish to narrow the gap between people and the natural elements.

The Art Newspaper:The scope of your work is really striking. How would you characterise it?

Eiko Tomura: We regard our projects, large or small, as having equal value. Often, we work with many different scales: sometimes it might be the environment on a planetary scale, other times a more human scale, or even the scale of micro-organisms. The very small environment that a single leaf produces, the large scenery that a building makes, the people that use those spaces and so on: we believe that, by equally considering many different scales in our design, we can discover new possibilities.

Eiko Tomura © Eiko Tomura Landscape Architects; courtesy Art Week Tokyo

You playfully suggest that having no function might liberate the experience of the AWT Bar and make it more open. How does your design maintain a balance between being playful and practical?

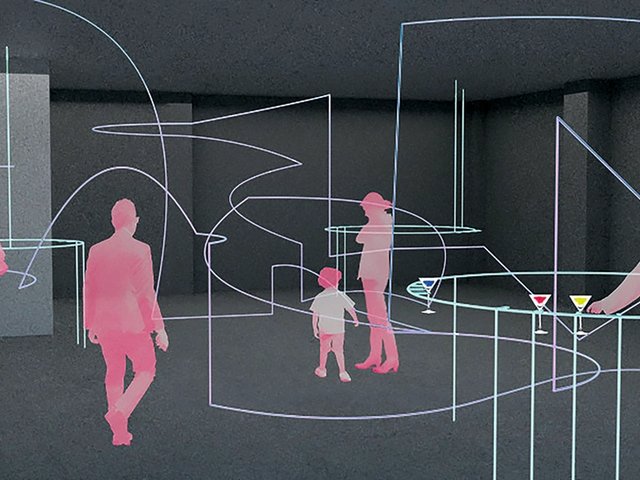

Even if our design for the bar may be a bit more difficult to use than usual, we thought that it’s going to lead to a more interesting space. We humans are flexible, and able to discover how to easily use something. At first glance the bar might seem devoid of functions, but actually we have designed places to sit, to gather, flow lines and places to put glasses and food. They are just not clearly identifiable, hidden in the ambiguity of the space. For us, it’s an exploration of new ways to use a bar by eliminating the functions you would expect to be there. They might cease to be just functions and become elements of the scenery or of the environment as well.

Compared with other cities, are there more unusual spots in Tokyo to eat or drink?

There are, but almost all of them are self-contained. Although Japan has a culture of eating and drinking while enjoying the seasons, the scenery and nature, it seems that many of those things are now excluded. In Paris, where I lived, there was a greater connection between food and the outdoors: you can enjoy a picnic on the banks of the Seine, or have lunch with the sun peeking out from between the restaurant and narrow sidewalk. Unfortunately, this way of enjoying food is disappearing in Tokyo. Even though it has rivers, the sea and sloping terrain, I feel there is a gap now between those elements and people. I think it would be great if you could enjoy Japanese food-and-drink culture in a richer variety of environments.

What is next for your studio?

We are working on projects of various scales, both domestic and abroad, in the United States, Taiwan and South Korea. We want to continue broadening the field of landscape architecture, especially here in Japan. We believe it has the potential to lead the other fields in multidisciplinary projects, through the design of the connections between cities, architecture, the scenery and the environment.

• AWT Bar, emergence aoyama complex, 5-4-30 Minami-Aoyama, Minato-ku, 7-10 November, 10am-10.30pm (last orders at 10pm)

Photo: Katsuhiro Saiki; courtesy Art Week Tokyo

Masters of mixology

Artist-curated cocktails offer thoughtful tipples

Creativity often means seeking out new forms of communication and collaboration. The bespoke cocktails for this year’s AWT Bar are just such a case, with three visual artists teaming up with the mixologists at Wall Aoyama to concoct liquid meditations.

The performance artist Ei Arakawa-Nash focused on embodying the Western image of autumnal Japan. The result, called Autumn Gone after a song by the popstar Yumi Matsutoya, is a slow-sipping botanical confection. With gin and a rum-based persimmon liqueur as the main spirits, it packs a punch but doesn’t overwhelm, skewing more sweet than fiery, with a syrupy texture from suspended pulp. A dash of Aomori-made cassis adds dark threads to the amber liquid that perfectly match the brown capillaries of raw persimmon flesh. It is languid and rich, a snifter drink for rambling fireside debates and endless November nights.

Photo: Katsuhiro Saiki; courtesy Art Week Tokyo

Meiro Koizumi, meanwhile, brings his curiosity about social behaviour to a high-concept drink called Ritualistic People. It explores how language influences perception and comes with a small instruction booklet to guide the drinker through the multi-sensory experience. The cocktail is clear as water but deeply aromatic and mildly sweet, served with a crimson ball of ice. Every element, down to the glassware and presentation, lends to the sleight of senses, making this cocktail as much a performance piece as a gustatory creation. To say more might spoil the trick.

Photo: Katsuhiro Saiki; courtesy Art Week Tokyo

The most visually striking contribution is The Most Terrifying White, a monochrome nod to the suminagashi art of paper marbling. Tabaimo invites drinkers to sully the purity associated with whiteness and reveal the ugliness underneath. A snowy mix of cream, milk, yoghurt and white curaçao is shaken with ice and served with a pipette of charcoal-blackened absinthe. Each drop creates dynamic and ephemeral Rorschach blots of chemical interaction until the once unblemished white becomes a murky grey. Unappealing as it looks, the medicinal absinthe adds a pleasing complexity to the lactic sweetness. It goes down easily, revealing the secret hidden by the white’s opacity: a lumpen garnish of dried sweet potato coated in tart curdled cream.