The demand for works by historical women artists continues to intensify, bolstered by acclaimed institutional exhibitions such as that of the 17th-century Italian artist Artemisia Gentileschi at the National Gallery, London in 2020. In 2021 Sotheby’s launched an annual themed sale, called (Women) Artists, whose inaugural edition saw 82% of the lots sell and eight works fetch at least triple their high estimates after fees. In March this year, the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam acquired a portrait by the 17th-century Dutch artist Gesina ter Borch for $3.3m at Tefaf Maastricht.

This rush of activity is generally seen as a long-overdue corrective for perceived historical biases. Yet auction results from past centuries upend the notion that works by women have only recently become sought-after. Around 500 transactions sourced from the Getty Provenance Index show that such pieces in fact made up a robust niche of the auction trade from 1700, when Paris supplanted Amsterdam as the centre of European art commerce, until 1850, which scholars often consider the dawn of Modernism.

Although the turbulence of French economics and politics limits the conclusions that can be drawn from this sample—for example, France’s national currency changed three times in these 150 years, making it nearly impossible to compare sales by value across the era—the results reveal that today’s bustling market for works by female Old Masters is in several respects eerily similar to its counterpart in 18th- and 19th-century Paris.

Identifying history’s female superstars

Of the 50 women artists whose works were traded in the Paris art market from 1700 until 1850, 60% were French, 20% hailed from the Northern school (comprising German, Flemish and Dutch artists), 10% were Italian and the remaining 10% were a mix of British, Swiss and unknown nationalities. Even after accounting for the small subset of artists whose country of birth differed from that of their most active market—the Swiss-born Angelica Kauffman, for instance, made most of her sales in England—auction records nonetheless show that this niche of the trade was already international hundreds of years ago.

Members were described in catalogues as ‘famous women’ or ‘distinguished women’, indicating there was such a thing as a female art superstar

It was also surprisingly focused on art that was then contemporary: only eight (16%) of the 50 artists were inactive by 1700. Several members of this group are both well-known and in demand today, led by Artemisia, Ter Borch and Elisabetta Sirani.

This means 41 of the 50 female artists (82%) in question were actively producing new works while their older pieces were also being sold at auction. (One artist, Maria Sibylla Merian, qualifies for neither category, since she died in 1717, more than 40 years before her first auction result.) Seven members of the contemporary group were even described in the catalogues with variations of the phrase “famous woman” or “distinguished woman”, indicating there was such a thing as a female contemporary art superstar in 18th- and 19th-century Paris.

Examples include Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun, Rachel Ruysch, Rosalba Carriera and Kauffman, all of whose works have been the subject of fierce competition among private and institutional collectors in recent years.

Just as in the contemporary art trade of our lifetime, a small minority of artists accounted for a large majority of the women-made works sold at Parisian auctions from 1700 until 1850. Just eight artists (16%) were responsible for 70% of the auction sales by volume among this group, with each woman accounting for at least 20 lots sold.

Sirani, with 42 lots sold, is the only one of these eight superstar artists who was inactive during the 150 years in question, making her an Old Master even to 18th- and 19th-century buyers in France. The other seven women were all creating new works while auction bidders competed for their older ones. They were a mix of French académicians—that is, members of Paris’s Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture—such as Anne Vallayer-Coster (30 lots sold) and Vigée-Le Brun (24); French non-académicians such as Marguerite Gérard (31) and Jean-Philiberte Ledoux (23); and artists from outside France such as Carriera (121), Ruysch (42) and Barbara Regina Dietzsch, with 38 lots sold (though this figure is open to question, as even specialists admit difficulty in distinguishing Dietzsch’s work from that of her sister, Margareta Barbara Dietzsch).

Lessons from the buy side

An examination of who was buying art by women during this period is also revealing. Although female patrons such as the salon hostess Marie-Anne Doublet, the Madame Du Barry (the last mistress to King Louis XV) and the Opéra-Comique dancer Marie-Anne-Xavier Mathieu sporadically acquired works by women artists, the most prolific buyers were all men. The five most active were the French art dealers and auctioneers Jean-Baptiste Pierre Le Brun (the husband of Vigée-Le Brun, who purchased 30 such lots), Alexandre-Joseph Paillet (18), Pierre Remy (18), Pierre-François Basan (17) and the father-son dealer duo François and François-Charles Joullain (15).

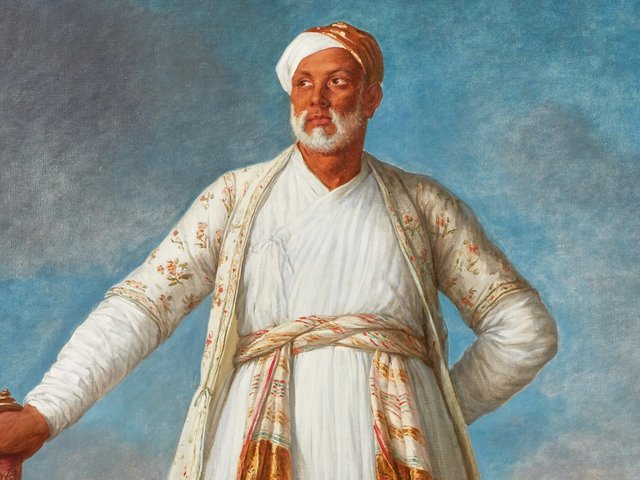

Elisabetta Sirani’s study for The Baptism of Christ (1658). Though she died in 1665, her work was already popular at auction in the 18th and 19th centuries

Public Domain/Alamy Stock Photo

These dealers—each of whom was almost certainly buying on behalf of clients at least some of the time—collectively purchased works by 20 different women artists. It is no surprise that the aforementioned superstars are prominent on their lists of acquisitions. Carriera and her pastel portraits, for instance, became a sensation across Europe after her triumphant visits to patrons in Paris in the 1720s, and Sirani’s artistic prowess had already been canonised by the 17th-century art historian Carlo Cesare Malvasia. The dealers also frequently purchased pieces by women whose reputations had been made in the Salons, such as Vallayer-Coster, Vigée Le Brun and Marie-Denise Villers.

Works on paper comprised a majority of the female-made lots traded under the hammer during this era. Around half of the 42 Sirani works sold were drawings, and several other women artists prevalent in the auction sale archives frequently worked on paper, including Carriera, Kauffman and Merian. This makes intuitive sense: since drawings typically take less time to create than paintings or sculptures, artists interested in working on paper could typically produce more of them, leading to a greater supply of their works in the market and thus a higher probability that a large number of those works could sell at auction.

The dark side of demand

The women whose auction markets outlasted their lifetimes were the exceptions in this period. More distressing, a closer look at the rest of the field suggests that the demand for their works may not have been for “their” works at all.

Around one-third of the female-made pieces purchased by the five dealers mentioned earlier had direct links to male artists. Every work by Antoinette Hérault traded at auction was a copy after a piece by a canonical Italian man, such as Raphael, Guido Reni and Francesco Albani. Similarly, the auction catalogue described one painting by an unknown “Mademoiselle Gaudon” as being in the style of the painter Jean-Baptiste Santerre. Dealers also purchased paintings by Ledoux and Geneviève Brossard de Beaulieu that the lot listings explicitly tied to their male teacher, Jean-Baptiste Greuze.

These findings align with the predominant systems through which historical women became artists: marriage or familial relationship to male artists. This phenomenon was most famously examined by the art historian Linda Nochlin in her 1971 essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? More recently, the historian Paris Spies-Gans, who analysed the educational background of female artists in Paris from 1760 until 1830, found that around half were either born into a family with an artist (around 29%) or related to an artist by marriage (around 18%). Only around 13% had a female teacher who was not a family member.

Similar patterns emerge among some of the top consignors of works by women, too. Beyond the professional dealers, some of the figures who most frequently offered such lots via auction had direct personal connections to the female artists in question. The German painter Johann Anton de Peters consigned eight works by his sister-in-law Mary de Villebrune at auction, six of which sold. The collector Blondel d’Azincourt, a noted patron of the artist François Boucher, consigned six lots by Boucher’s wife, Marie-Jeanne Boucher, that all found buyers.

A deeper dive into this period’s auction results would provide only one part of this complex market picture, though. Further discoveries would no doubt be brought to light through research into, say, the surviving documentation around the direct commissioning of women artists or records from estate sales of this era in Paris. Yet the patterns visible in Parisian auction results until 1850 still manage to foreshadow the internationalism, the superstar economics and other dynamics of today’s markets for both historical and contemporary female artists.

They also presage at least one substantive change in the art trade in the centuries since. Some cynicism is certainly warranted regarding how much of the 21st-century buying and selling of women-made work is driven by the pursuit of profit. But even the crassest speculators are at least treating most works by female artists as objects made valuable on their own merits rather than because of their behind-the-scenes ties to men. This is a kind of progress—but it is also fair to say that, after a few hundred years, women still deserve much more.