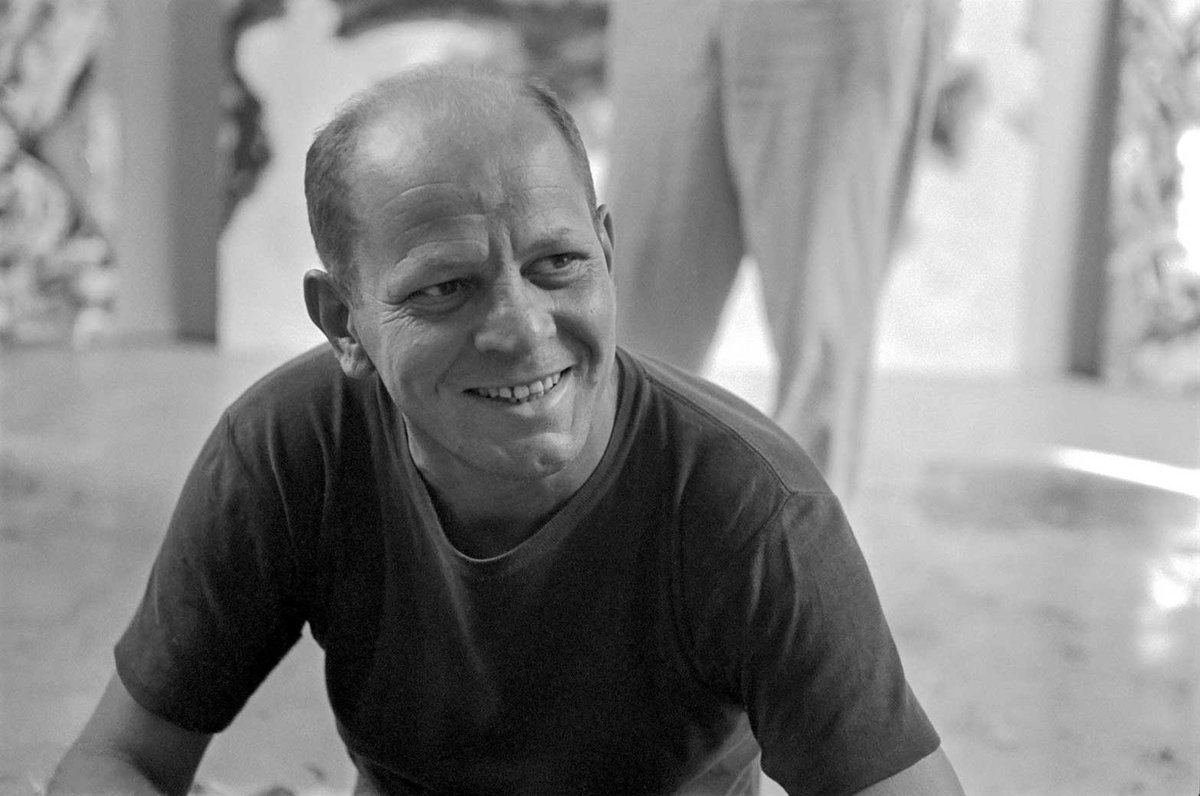

The Pollock-Krasner Foundation has selected New York’s Kasmin gallery to globally represent its holdings of Jackson Pollock works, which had been handled for decades by Manhattan’s Washburn Gallery until that dealership’s closure this spring. The expanded partnership marks the first time both halves of the pioneering Abstract Expressionist couple will share a gallery since the late 1960s, when Pollock and Krasner were represented by the Marlborough-Gerson Gallery.

“For Pollock, we didn’t consider anyone else but Kasmin,” says Caroline Black, the executive director of the Pollock-Krasner Foundation. She adds that the gallery is “well positioned” to shepherd Pollock’s work “because they have such a strong understanding of Krasner and have been a great partner with us”.

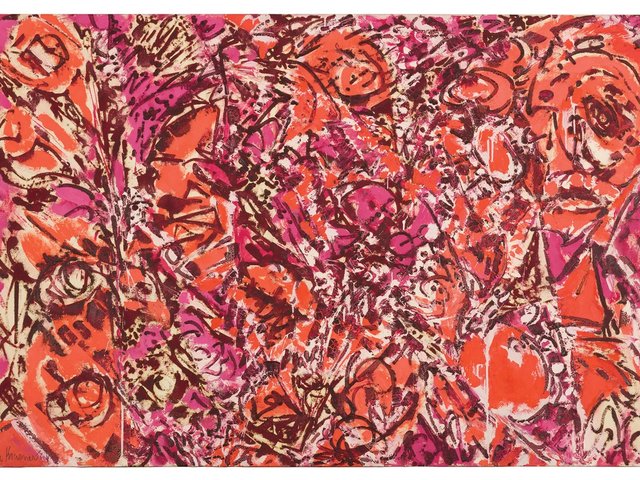

Kasmin began representing Krasner’s work in 2016. Over the past eight years, the gallery has substantially improved her visibility and market position while the art world has been broadly reassessing undervalued women artists. In particular, Kasmin has helped expand the recognition of Krasner’s practice beyond her sweeping gestural masterpieces in pinks and greens from the late 1950s and early 1960s. The gallery has mounted four solo exhibitions—most recently of her lesser known geometric abstractions made from 1948 until 1953—and two solo art fair presentations to date; it has also provided comprehensive support to Krasner’s travelling European retrospective, which opened in 2019 at the Barbican Centre in London.

Kasmin are really thoughtful about where they place pieces

“When we took over Krasner, there were paintings insured for $500,000 that would sell down the road for $4m or $5m,” says Eric Gleason, Kasmin’s head of sales. Krasner’s 1960 canvas The Eye is the First Circle brought $11.7m (with fees) in 2019 at Sotheby’s in New York, shattering her previous auction record of $5.5m (with fees), set in 2017 at Christie’s in New York, and showing the magnitude of the demand for her work.

“Kasmin’s strongest attribute is they’re in it for the long game and are really thoughtful about where they place pieces,” says Black.

Selling its holdings to fund artists

The successor to the estates of both artists, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation was established according to Krasner’s wishes after her death in 1984. Black emphasises that its mission is to steward the legacies of Pollock and Krasner and to financially support working artists. When sales are made from the foundation’s holdings, the proceeds are used to bolster its endowment, which currently totals $91m and “turns into life-changing grants”, Black says.

Unlike most grants, for which artists generally must be invited to apply, those from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation are open to all applicants (within certain guidelines) and awarded solely on artistic merit, typically in amounts between $30,000 and $50,000, on a rolling basis without deadlines. The funds are also largely unrestricted, meaning that they can often be used for anything from studio supplies and rent to medical bills and childcare. Among the notable artists who have received grants from the foundation are Walton Ford, Stanley Whitney, Amy Sherald and Njideka Akunyili Crosby.

Celebrating its 40th anniversary next year, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation has given more than $90m to date via 5,100-plus grants to professional artists and organisations supporting them in 80 countries. Of the around 400 active artist-endowed foundations in the US, only a handful—including the Joan Mitchell Foundation and the Adolph & Esther Gottlieb Foundation—make direct grants to artists, but none of these rival the around $3m gifted annually by the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, according to Christine Vincent, the project director of the Artist-Endowed Foundations Initiative at The Aspen Institute.

Stories yet to be told

Kasmin’s representation of Pollock is now poised to enhance the Pollock-Krasner Foundation’s dual mission. Although the foundation no longer owns any of Pollock’s large-scale, mature drip paintings—some of which have sold for prices in the nine figures—it retains smaller paintings, works on paper and prints from every decade of the artist’s career. “What I find exciting about them is that they’re all pieces Lee chose to keep,” Black says. “They meant something to her.”

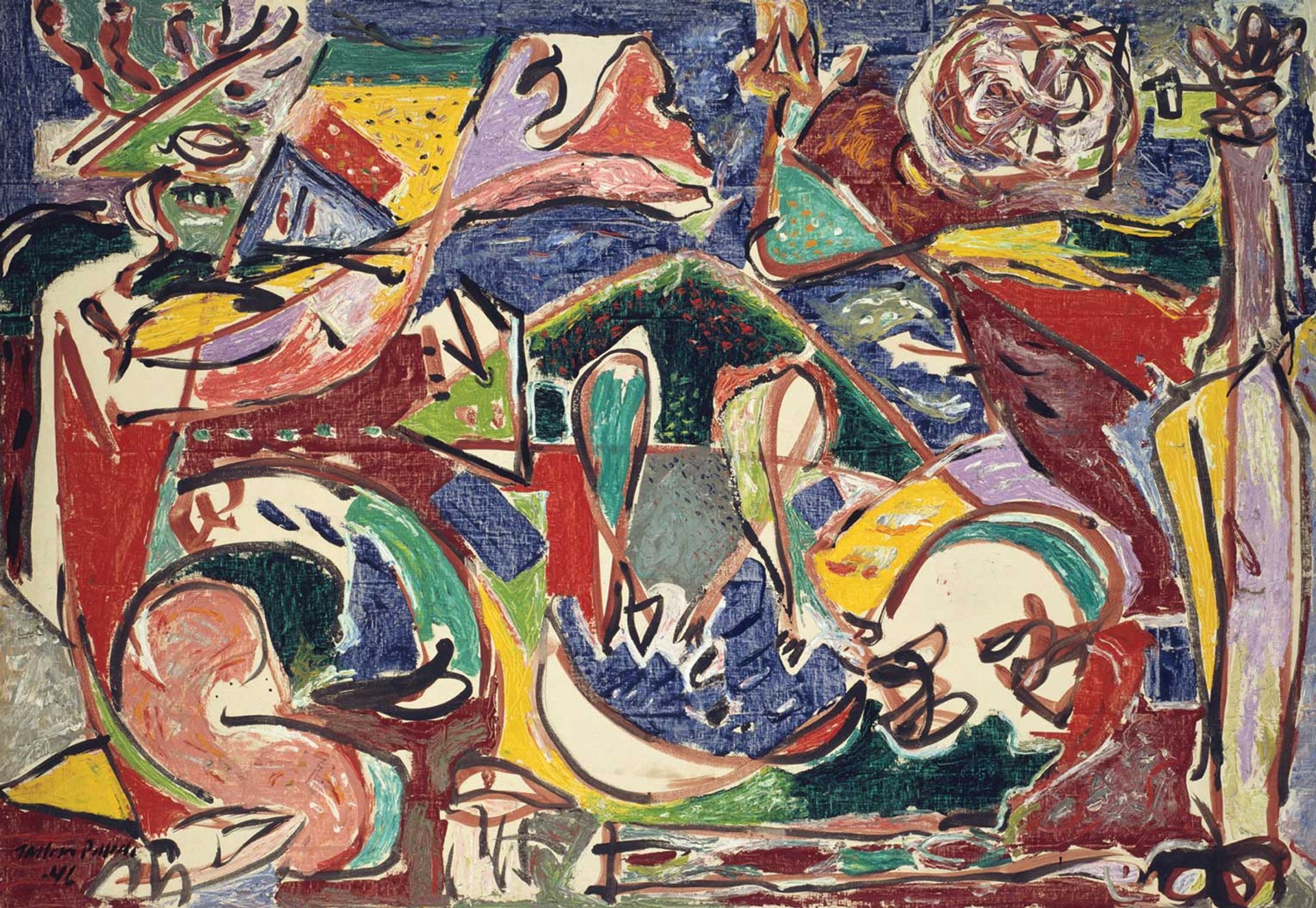

Since the Pollock-Krasner Foundation’s formation in 1985, its holdings have included works such as Pollock’s 1946 painting The Key

The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY; © 2024 Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pollock may be one of the most foundational painters of the 20th century, especially in America, Gleason says, but “there are still parts of his personal history and painting history that are very undertold”.

At Frieze Masters in London (9-13 October), Kasmin will be showing a cache of Pollock’s so-called psychoanalytic drawings: works made during the period from around 1939 until 1942, when the artist was undergoing Jungian analysis, and that exhibit influences from the Surrealists, Mexican muralists and Picasso.

That presentation will be followed by the 15 October opening of Jackson Pollock: The Early Years (1934-1947), an exhibition at the Musée Picasso Paris on the artist’s rarely exhibited works preceding his drip paintings. The show traces Pollock’s development through the impact of multiple influences, including Thomas Hart Benton and other American regionalists, Native American art and the European avant-garde. Of the around 100 works in the exhibition, 26 are on loan from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation.

According to Black, the goal of the foundation’s partnership with Kasmin is less to raise Pollock’s price points than to shift the narrative around his legacy a bit. “We all know he struggled, but he really tried to work on himself with therapy for decades,” she says. “I think it’s time to recontextualise Pollock through a 21st-century lens, to look at the arc of addiction and relapse.”