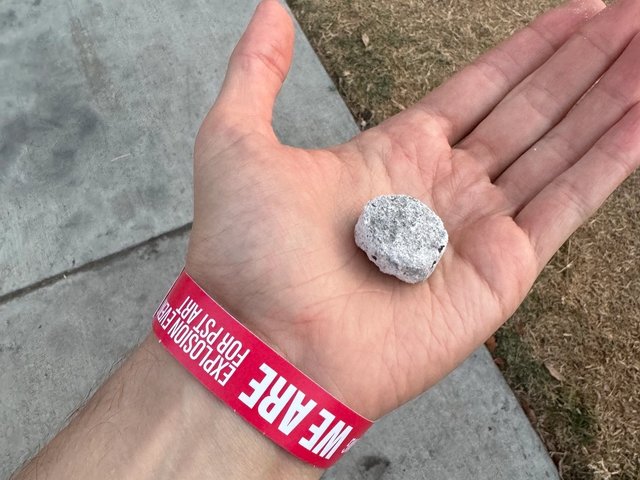

It was not an image you would ever associate with an epic cultural celebration. At the end of Cai Guo-Qiang’s fireworks show at the Los Angeles Coliseum on Sunday evening (15 September) came a thunderous set of explosions above the American football field that had spectators crouching or flinching and covering their ears. Then, as ash from the pyrotechnics rained down on the crowd, several people could be seen taking shelter under their jackets or covering their mouths with their own shirts as makeshift masks.

Yes, some VIP guests at the official kick-off event for the third edition of PST Art—a $20m extravaganza billed as the largest arts event in the US—looked, at least momentarily, like refugees from a California wildfire.

Judging from Cai’s introduction to his event, called WE ARE, this was not entirely unintentional. In between explosions, which mainly took the form of drone-delivered daytime fireworks above the stadium while viewers occupied the football field, the internationally acclaimed Chinese artist told a story about humanity’s complex relationship to artificial intelligence (AI). He narrated much of it himself, with the help of an AI programme translating his Chinese to English on the spot in a simulacrum of his own voice.

Some attendees covered their heads at the end of WE ARE, the official opening event for PST Art Photo: © Jori Finkel

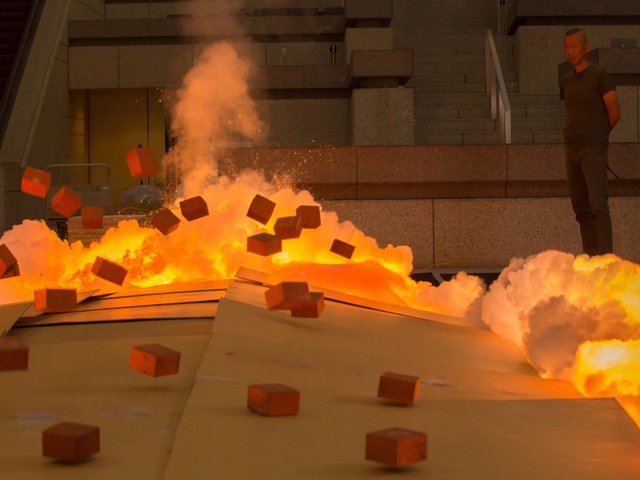

Some fireworks were gorgeous: huge bouquets of orange, red and blue pigment hovering above green stems looked like flowers opening up. He called these images Birds of Paradise, noting: “This is a gift for the city of Los Angeles.”

But the violence of his finale, labelled on the display screens as “Part V: Divine Wrath”, was hard to shake, especially considering the Coliseum’s location in South Los Angeles. Was Cai aware of the history of fires nearby during the Watts Rebellion of 1965 and later the 1992 Los Angeles riots? Was anyone in the neighbourhood warned about the noise levels? (The roughly 5,000 guests were not, as far as I could tell, except for one man who was kind enough to hand out earplugs to his nearest neighbours.)

The experience was more jarring considering how many of the artists in this edition of PST Art, subtitled “Art+Science Collide”, are dedicated to healing the environment and raising awareness of manmade threats. The Hammer Museum, for instance, has just opened a PST Art survey called Breath(e): Toward Climate and Social Justice, featuring artists who address, per an official text, “anthropogenic disasters such as deforestation, ocean acidification, coral reef bleaching, water pollution, extraction and atmospheric politics”. The Brick has a timely ecofeminism show that explores alternative feminist and queer ecologies. Many other PST Art exhibitions take on a single issue, from water pollution to Indigenous fire management.

Colourful bird-of-paradise flowers seen above the Los Angeles Coliseum during WE ARE, which artist Cai Guo-Qiang's called his "gift to Los Angeles" Photo: © Jori Finkel

Cai has spoken thoughtfully about his reason for preferring daytime fireworks (made of gunpowder and coloured pigments) over traditional nighttime displays: they use less gunpowder, creating less of an environmental impact and odour. But he freely admits there is still sulphur and noise pollution created, and the fact that the Getty chose any fireworks to launch what just might be the most ambitious presentation of environmentalist art to date is perplexing.

This underscores a persistent tension in PST Art, present since it first launched in 2011 under the harder-to-Google rubric “Pacific Standard Time”. On the one hand, PST Art is a Getty project, with the institution choosing the overarching topic like this edition’s “art and science” theme, issuing millions in grants to local organisations and then providing marketing support. On the other hand, the Getty encourages a grassroots, collaborative sensibility among its “partners”, with the 70-odd participating institutions each maintaining flexibility and independence in terms of which particular exhibitions they decide to develop and how.

The result this time is that PST Art is heavy on climate change shows—and relatively light on other scientific subjects and the incursion of Big Tech into our lives. This is not the Getty’s doing but somewhere along the way its leaders must have noticed the core themes that emerged from their investment. And yet they decided anyway to go with pyrotechnics, no matter how counterintuitive or counterproductive, to kick off the PST Art season.

Even if you found Cai’s fireworks spectacular, the messaging was bizarre. Or, as one visitor said when leaving the stadium: “Everything about it was wrong.”