Dia Art Foundation was established in New York in 1974, dedicated to commissioning and presenting major public works of art in unprecedented ways. Now, this unique institution is entering a new era that has found it squaring its founding principles with the needs and requirements of a very different world. Dia (the name comes from the Ancient Greek word for “through”) has never operated like a conventional museum or funding organisation. In the words of its three founders—the art dealer Heiner Friedrich, Philippa de Menil (now known as Fariha Fatima al-Jerrahi, heir to the Schlumberger oilfield services company) and the art historian Helen Winkler Fosdick—“The purpose of the foundation is to plan, realise and maintain public projects which cannot be easily produced, financed or owned by individual collectors because of their cost and magnitude.”

Such legendary largesse led to the establishment of often epic permanent works of Land Art, many of which Dia continues to maintain. These include Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970), Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels (1973-76) and Walter De Maria’s The New York Earth Room (1977), The Broken Kilometer (1979) and The Lightning Field (1977), as well as Dia Bridgehampton, the former fire station and church where Dan Flavin installed permanent fluorescent-light sculptures in 1983. Dia was also instrumental in the initiation of James Turrell’s epic, ongoing project Roden Crater and in facilitating Donald Judd’s expansive ambitions in Marfa, Texas, to create what is now the Chinati Foundation.

Fifty years on, Dia’s artist-centric ethos remains. “We may no longer have the limitless resources of our founders, but our mission is still to put artists first, second, third and fourth,” Jessica Morgan, Dia’s director since 2015, tells The Art Newspaper. But while Morgan and her team assert that “Dia is still the place that says ‘yes’ to artists, and then we figure out how to do it, no matter what”, when she first started the job, it was evident that if Dia wanted to regain its relevance, it had to change—and fast. “We were the epitome of a dead-white-male institution,” she says. “We inherited a collection with two female artists in it, and the only artist of colour we could point to was On Kawara.”

Dia quickly entered what Morgan diplomatically describes as “a period of reinvigoration”. The past nine years have seen the diversifying of Dia’s programming and collection as well as the consolidation and reactivation of its exhibition spaces both in New York City and in Beacon (in upstate New York), where Dia has occupied a vast former box-printing factory since 2003. Behind the scenes, Dia’s workforce has unionised, and some vigorous fundraising has seen its finances stabilise, but the most visible institutional shift is in the artists who have entered its fold.

No longer telling a partial story

“The 60s and 70s were this extraordinary period, but we were only telling an incredibly partial representation of that story,” Morgan says. “The last few years have seen a very deliberate effort to bring into our midst artists who were rightfully part of that history but who were written out. So it was about restoring history, and then beginning to look more globally, beyond just the US and Europe.”

This process has been a rapid one. When Morgan first joined Dia, there were works by around 20 artists in the collection. Now there are 71, and 24 of them are women, including Meg Webster, Dorothea Rockburne, Senga Nengudi and Joan Jonas.

“I first went up to Dia Beacon before it was renovated, and I recorded the space,” Jonas says. “I did one of my major performances there with Jason Moran, and they gave me the whole basement in which to work. I’d say it was one of the best situations that I’ve had with my work.”

Expanding the collection’s Asian and Latin American representation is now a priority. Since 2017, Dia has owned a series of major works by Lee Ufan who, in addition to being a key member of Japan’s 1960s Mono-ha movement, was closely associated with Richard Serra.

Black artists also play a major role at Dia. Works by the conceptualist Charles Gaines, the sculptor Melvin Edwards and the painter Sam Gilliam have recently entered the collection. “When we brought Sam here, he said he wanted to be part of Dia, because Donald Judd was his favourite artist and it meant so much to him to be having that conversation,” Morgan says.

Sometimes, newer arrivals can have a spiky relationship with the works in Dia’s core collection. Morgan describes Nengudi, whose work is currently on long-term view at Dia Beacon, as deeply critical of the weight, scale and resources of much of the work of her generation. “Rather than using rolled steel, she’s showing she can make something just as significant using coffee, dry-cleaning bags and kitty litter,” Morgan says.

A crucial development in futureproofing Dia has been rebooting its presence in New York. On arriving at Dia, Morgan vetoed a proposed $50m plan to build it a new home. Instead, in 2021, she opened Dia Chelsea, which consolidated and extended three of Dia’s existing buildings on West 22nd Street. “We’d lost a connection to the city by not being open in New York for so long and just having Beacon—so we stopped renting out our real estate in Chelsea and started using it again for shows,” she says, noting that it has always been Dia’s practice to show work in the kinds of repurposed, industrial spaces that artists often use as studios—“highly practical, with cement floors, no extraneous details, where the architecture steps back”.

Live performance and sound works

The rough-hewn spaces of Dia Chelsea display substantial temporary exhibitions, mostly by younger artists. In keeping with the Dia ethos, these are developed in close association with the artists and for an open-ended period, which can stretch into several years. The shows mark Morgan’s wider reactivation of Dia’s commissioning programme, which had fallen dormant despite being Dia’s initial raison d’être. Now, the commissioned works that activate Dia’s spaces often end up in the foundation’s collection. For example, Dia recently acquired Cielo terrenal (earthly heaven, 2023) by the Colombian artist Delcy Morelos, an extensive and pungent installation of soil, ceramics and salvaged artefacts on view at Dia Chelsea until 20 July.

Installation view of Carl Craig: Party/After-Party at Dia Beacon, New York, 2020

© Carl Craig. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York, courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York

Dia’s foregrounding of live performance and sound works is another way the foundation’s radical past has manifested in its current programme. Morgan says it was important to embed herself in Dia’s history before she could start adding to its collection; her first major Dia project was the 2015 re-creation in Chelsea of La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela’s Dream House (1979-85). Young and Zazeela were the first artists to work with Dia, and their Dream House took the form of a sonic-and-light environment that hosted durational musical compositions in a three-storey Tribeca building acquired by the foundation.

Other live Dia works have included performances by the dancers and choreographers Trisha Brown and Steve Paxton. In 2020, a new approach was signalled by Party/After-Party, a site-specific sound-and-light installation by the Detroit techno-music producer Carl Craig. It took five years to make, and it converted Dia’s basement into a “warehouse party church”, Craig says. “My career in the art world is something that I attribute to being discovered by Dia, and I’m happy that not only did I do a show there, but also that Party/After-Party is in the permanent collection.”

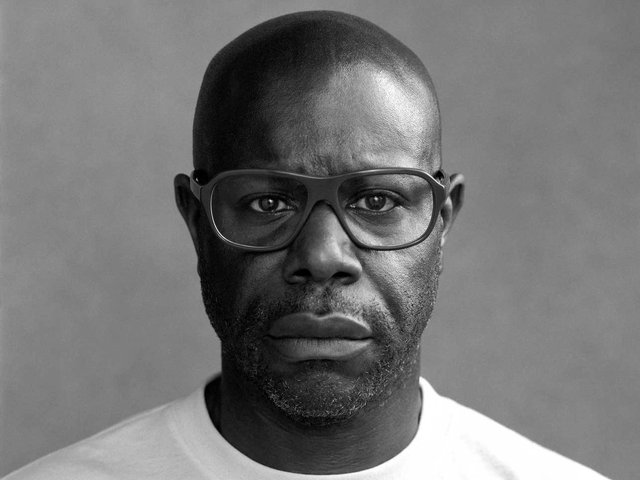

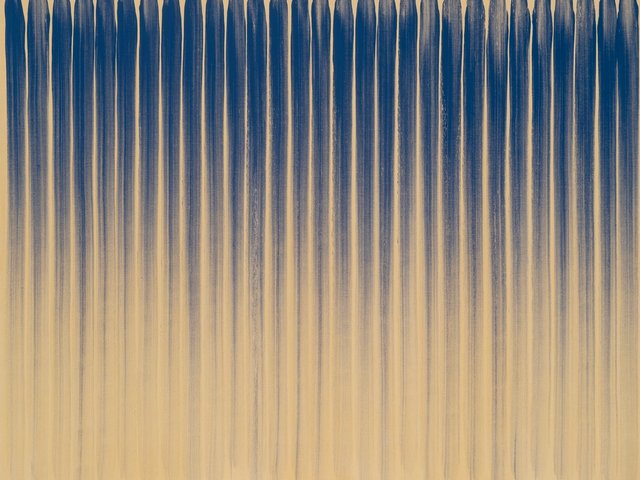

At Dia’s 50th-anniversary benefit lunch in May, the co-founder Al-Jerrahi presided with Morgan over more than 600 figures from the foundation’s past and present, 200 of whom were artists. The event marked the unveiling of Steve McQueen’s Bass (2024), a new commission for Dia Beacon’s 30,000 sq. ft lower gallery—the artist’s most abstract work to date, composed solely of light, colour and sound.

“If I look back to when I first started, we could never have jumped straight into showing Steve,” Morgan says. “But now that we’ve had a consistent engagement with sound, and have been commissioning and thinking about the contemporary artists who engage and respond to Dia, I couldn’t think of a better artist. It couldn’t be more in our language but also, at the same time, is completely in his language: it’s Steve’s Dia project, right?”