Strutting peacocks greet visitors outside the Manhyia Palace Museum in the centre of Kumasi, Ghana, where Asante royal treasures from two of the UK’s leading museums have recently gone on display.

Built in 1925 by the colonial authorities as the residence of Prempeh I, the Asante king who had been exiled to the Seychelles in 1900, the palace partly represented a symbolic act of reconciliation after five 19th-century Anglo-Asante (Ashanti) wars in what became the colony of the Gold Coast. It was during these wars that loot was seized, some of it ending up in UK museums.

The peacocks are the descendants of the birds given to the Asantehene (Asante king) by the Shah of Iran in the early 1970s. As Ivor Agyeman-Duah, the museum’s director, points out, they “scream to welcome” new arrivals.

Prempeh I lived in the Manhyia Palace until his death in 1931, when he was succeeded by Prempeh II. After the latter died in 1970 his successor moved into a more modern residence. Five years later the Manhyia building was opened to visitors as a museum (“manhyia” means “gathering of the people”).

Ivor Agyeman-Duah, director of Manhyia Palace Museum, anticipates that the loans could increase visitor numbers from 90,000 to 200,000 a year Nkansahrexford

The palace’s ground floor remains much as it was, filled with 1920s British middle-class furniture. Among the curiosities on view are a vintage telephone and a radio encased in a replica of a symbolic Asante stool. Another object on display may come as a surprise: a medal awarded to Prempeh II in 1937, when he was made a knight of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire. Adjacent to the ground floor is a modern extension, which houses effigies of earlier Asantehenes, wearing traditional garb.

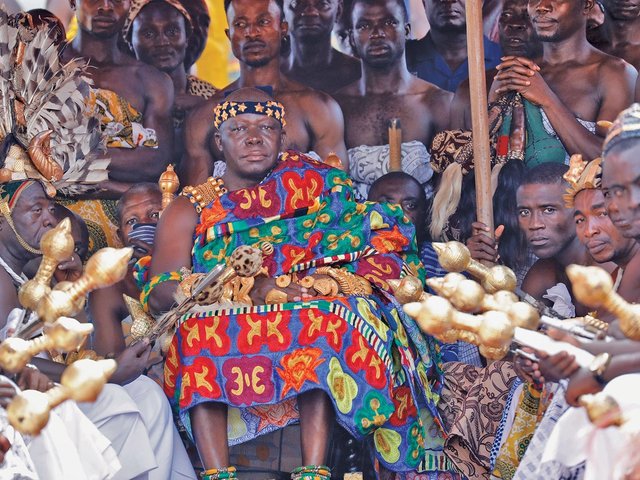

The objects from the British Museum (BM) and the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London were unveiled on 1 May in an impressive ceremony presided over by the present Asantehene, Otumfuo Osei Tutu II. The V&A was represented by its director Tristram Hunt and the BM by a trustee, Chris Gosden.

Speaking at the event, Hunt acknowledged the sentiments that surround the returned objects. He spoke of “history tainted by the scars of imperial conflict” and recognised “the enduring cultural, historical and spiritual significance these artefacts hold for the Asante people”.

Important distinctions between UK and US items

The UK loans are displayed in three glass cases. Most important are gold items, including soul-washers’ badges, a figure of an eagle and a symbolically charged peace pipe, as well as the important ceremonial sword known as the Mponponsuo. There are 15 objects from the BM (although Agyeman-Duah would ideally have liked 20) and 17 from the V&A. A fourth case has seven items from the Fowler Museum at the University of California in Los Angeles. Few other historic traditional objects are displayed elsewhere in the building.

Most of the returned items are colonial loot, seized by British troops during the Asante wars. During an 1874 operation the British looted and then blew up an earlier palace of the Asantehene. A few other loans were legitimately acquired, not in battle.

There is an important distinction between the items being returned from the UK and the US. Ownership of the seven Fowler items, which were donated to the Californian museum in 1965 by the UK’s Wellcome Collection, has been formally transferred to the Asantehene. He now holds ownership and is free to use the regalia for ceremonial purposes. The BM and V&A objects, however, are required to be treated as artworks. The UK museums are prohibited from deaccessioning, under acts of Parliament, and are therefore returning material as loans. This is initially for three years, with the option of a three-year extension. The delicate loan negotiations were led on the Asantehene’s side by Agyeman-Duah and his colleague Malcolm McLeod, a former BM curator.

Barnaby Phillips, who is writing a book about the Asante loans, attended the ceremony. “It was a moving event, the culmination of years of diplomacy,” he says. “Although the concept of a loan leaves many dissatisfied, there was a tangible sense of satisfaction that these objects were returning home.”

There are also differences between the two UK museums on colonial loot. Hunt would like to be able to restitute ownership of colonial loot, but is unable to deaccession. The BM is less keen on the idea of restitution (partly because of the Parthenon Marbles dispute), although it is open to loans.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the Manhyia Palace Museum received 90,000 visitors a year—60% Ghanaian and the remainder international. Agyeman-Duah hopes that with the new loans the number will rise to 200,000.

In a surprise move, Tutu II used the return of UK museum objects as an opportunity to question the sale of artworks by contemporary Ghanaian artists to buyers outside the country. He commented that much of their work is “bought by non-Africans with [an] interest in them, branded and marketed for bigger profits”. The Asantehene added: “When I next travel to England in the coming months [probably July], I will be meeting some of these Ghanaian artists, painters, goldsmiths and see how we can collectively work with some of the traditional art groups. When the modalities are set up, we will also work with private galleries in the country [Ghana] to at least retain some of their collections.”