In Teju Cole’s recent novel Tremor (2023), the narrator—a professor of photography at Harvard—considers a series of his photographs from Lagos. “They are portraits of unpeopled scenarios, planks, tires, culverts, basins, stones, ships, plants,” he describes. “I fear the demands that portraits of people make. Portraits are high risk and require familiarity, vulnerability, and strangeness.” In Pharmakon, the Nigerian American writer’s fourth photobook, we are shown another set of “unpeopled scenarios”. The photographs are quiet, serene, depicting trees and boulders, buildings, walls, parked cars, mountains, seas lightly disturbed by wind, Cole’s pastel light and subtle contrast hushing each image. As if to emphasise their lack of figures, an early picture shows a statue in a public park, wrapped in brown cloth, entirely covered, as if about to be removed for storage.

Best known as a writer of fiction and essays, Cole has nonetheless used photography in his reflections on the limits of vision. Throughout his work, Cole, who was born in 1975, is drawn to instances of cultural, historical and literal blindness. In 2011, he woke to find himself blind in one eye, a temporary loss of vision later diagnosed as papillophlebitis, a condition caused by perforations to the retina; while giving a lecture on the art of J.M.W. Turner, Cole’s protagonist in Tremor suffers “a medical episode”, losing vision in an eye for half a minute.

Speaking to the journalist Sean O’Hagan about the publication of his photographs in Blind Spot (Faber & Faber 2017), Cole explains that—because of the way the eye is structured—“the act of looking is limited”. “We only see a small part of what we are looking at,” he continues, “so there is a constant blind spot even with the kind of attentive looking that photography entails.” “‘We see the world’,” reads a passage in Blind Spot. “This simple statement becomes … a tangled tree of meanings. Which world? See how? We who?”

That we don’t know what—or where—we are seeing prompts us to pay renewed attention to the scenes and objects

The world of Pharmakon is hard to determine. The photographs are presented uncaptioned, undated and (in contrast to Cole’s previous work) without a specified location: some are reminiscent of Greece, while others could be Paris, New York, even Switzerland (the subject of Cole’s photographs in Fernweh, 2020). That we don’t know what—or where—we are seeing, however, prompts us to pay renewed attention to the scenes and objects on display. “A photo, even a good one, tends to simply show you what something looks like,” writes Cole in a recent essay for Mack Books (“In Praise of the Photobook”). “But if you sequence several of them … you see not only what something looks like, but how someone sees,” he writes. “Look at this, the photographer says, then look at this, then look at this one.”

Eerie abandonment

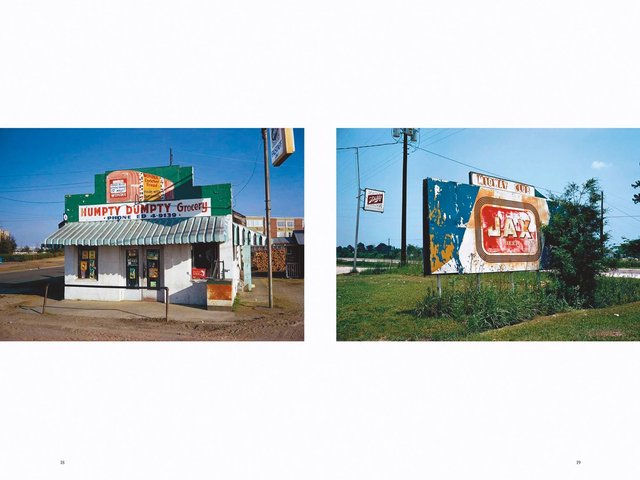

What we are shown in Pharmakon, time and again, is an environment that has been emptied: parks and streets devoid of people, unoccupied seats, bare walls and windowpanes, rocks and ruins, slowly eroding. Several photographs show scraps of paper taped or glued to walls, the remains of fliers and posters torn down and removed, as though the event they once referred to had been cancelled at short notice. While Cole’s pictures exude a kind of calm or tranquillity, they equally project an eerie feeling of abandonment. Early on, a tree sags heavily beneath the weight of its apples, many strewing the ground, perhaps because there is nobody around to pick them. Later, the few lights shining from a tower block seem almost left on by mistake; far from evidence of people living there, the lights evoke a hasty departure, as though the residents had left before the onset of a thing it might be safer to avoid (or flee from).

This feeling is compounded by the presence of a dozen short stories threaded through the publication, concentrated, enigmatic “snapshots” that depict a world of conflict, migration, detainment and departures. “Our group had a plan,” begins the first: “when the bus came the next morning, that would be our moment to make a break for it. Some of us would be captured. Some might be killed. But not all of us could be captured or killed: some would reach the trees.”

The duality of Cole’s photographs—both calm and lightly sinister—may explain this new book’s title, derived from a Greek word meaning either “remedy” or “poison”. Cole frequently presents a pair of images, the same scene photographed from slightly different angles, moments apart, the gesture (literally) of a double take, illustrating, possibly, the two modes they exist in: peaceful, disturbing. Self-consciously oblique, almost withholding, Cole’s photographs invite us to consider not only what but how we see, through whose lens, when, for what, and why. Speaking with the writer David Naimon in 2021, Cole offers some questions that might just as easily apply to his own practice: “Why is this person’s attention elsewhere? If it’s elsewhere, where is it?”

- Pharmakon, by Teju Cole, published by Mack, 200pp, over 100 colour images, £40/$50 (pb), 2 February