The genesis of Hold Still: A Memoir with Photographs lies in an unexpected invitation received by the American photographer Sally Mann (born 1951) to deliver the distinguished Massey Lectures at Harvard University. Filled with trepidation, she climbed into her attic to seek inspiration from the residue of her unexamined past: the stacks of letters, journals, childhood drawings and photographs that had been left untouched for decades. Here, she also discovered numerous twine-bound “ancestral boxes”, containing the “ghosts of long-dead, unknown family members”, from which an inordinate amount of dark secrets emerged: scandal, deceit, infidelity, addiction, domestic abuse and even cold-blooded murder. Across 24 generously illustrated chapters, Hold Still interweaves this curious and at times shocking ancestral history with Mann’s own spirited biography, as she seeks to understand the forces that have shaped her life and career as one of America’s pre-eminent photographers.

There were few signs that the rebellious, “near-feral child” from Lexington, Virginia, who barely wore clothes until the age of five and spent her teenage years riding horses, would pursue a career in the arts. Her despairing art tutor at Vermont’s exclusive Putney School described her as “too rigid” and “easily frustrated”. But it was Mann’s rapturous discovery of photography in 1969 that set her on a trajectory from which she never looked back. She writes: “I had found the twin artistic passions that were to consume my life.” The other passion is writing, and although this is barely discussed in the course of 500-plus pages, it is more than evident from Mann’s compelling prose and lyrical turns of phrase.

In the early 1990s, Mann’s series Immediate Family brought her significant acclaim and notoriety. It was an experience, she says, that “spun me near senseless”. These intimate black-and-white portraits of her three children growing up on the family farm—sometimes in the nude—proved too much for some critics, who accused Mann of child abuse and exploitation. The Wall Street Journal ran a particularly scathing op-ed that only added fuel to the fire. Judging by the amount of space given to defending this body of work, it is an episode that still rankles. “How can a sentient person of the modern age mistake photography for reality?” she asks pointedly.

Morbid collection

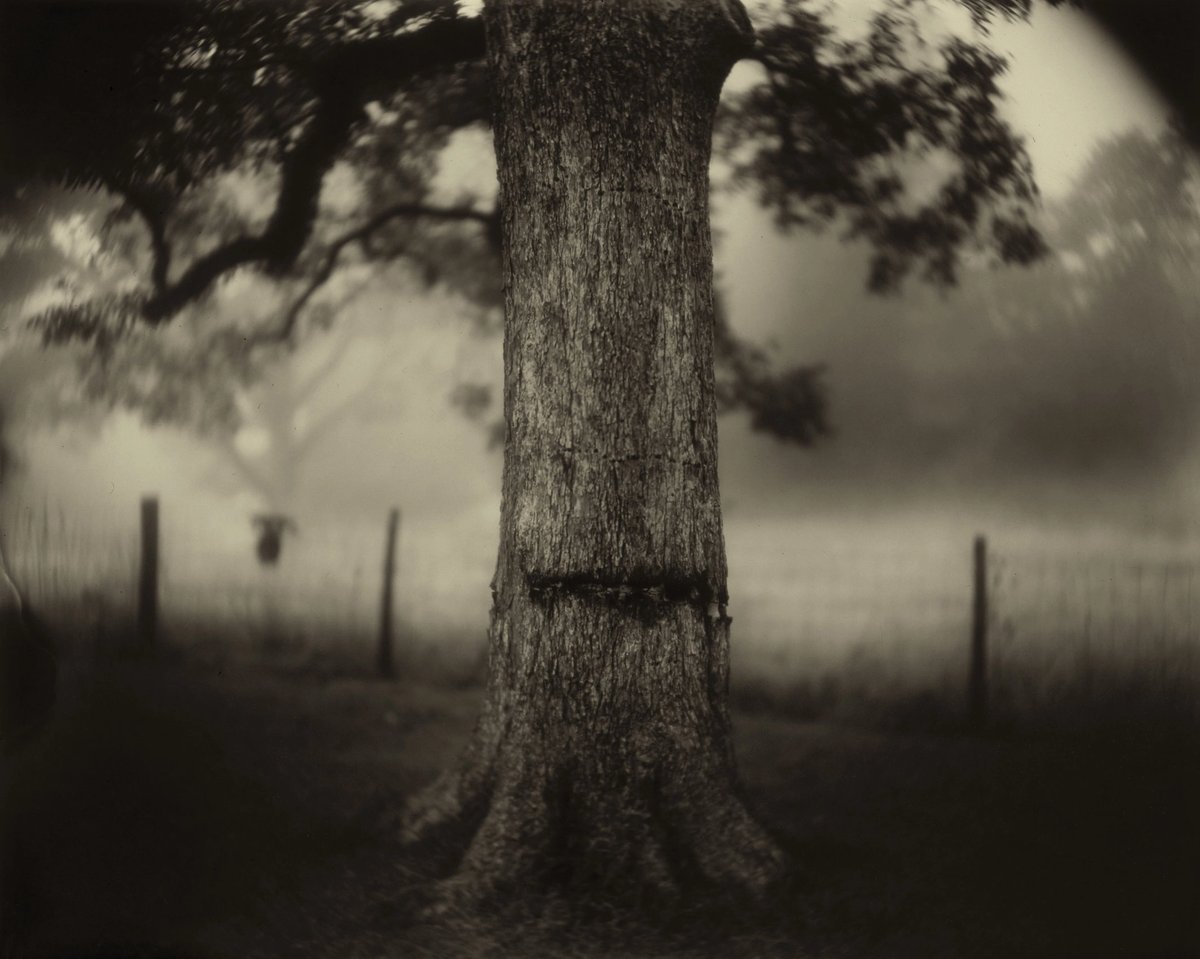

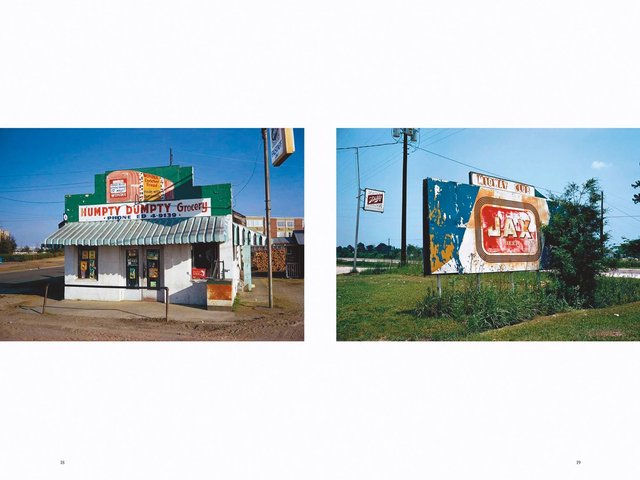

Mann’s subsequent series Deep South and What Remains are discussed at length with many images reproduced. For the former, she explored America’s southern states with her 8x10 field camera, finding evocative landscapes “haunted by the souls of the millions of African Americans who built that part of the country with their hands and with the sweat and blood of their backs”. The latter is a morbid collection of pictures taken at the University of Tennessee’s Anthropological Research Facility (a.k.a. “the Body Farm”), where donated corpses are left to putrefy in the open air for the benefit of science. Mann’s explicit photographs, though unsettling, are far less stomach-turning than her gruesome descriptions of the cadavers.

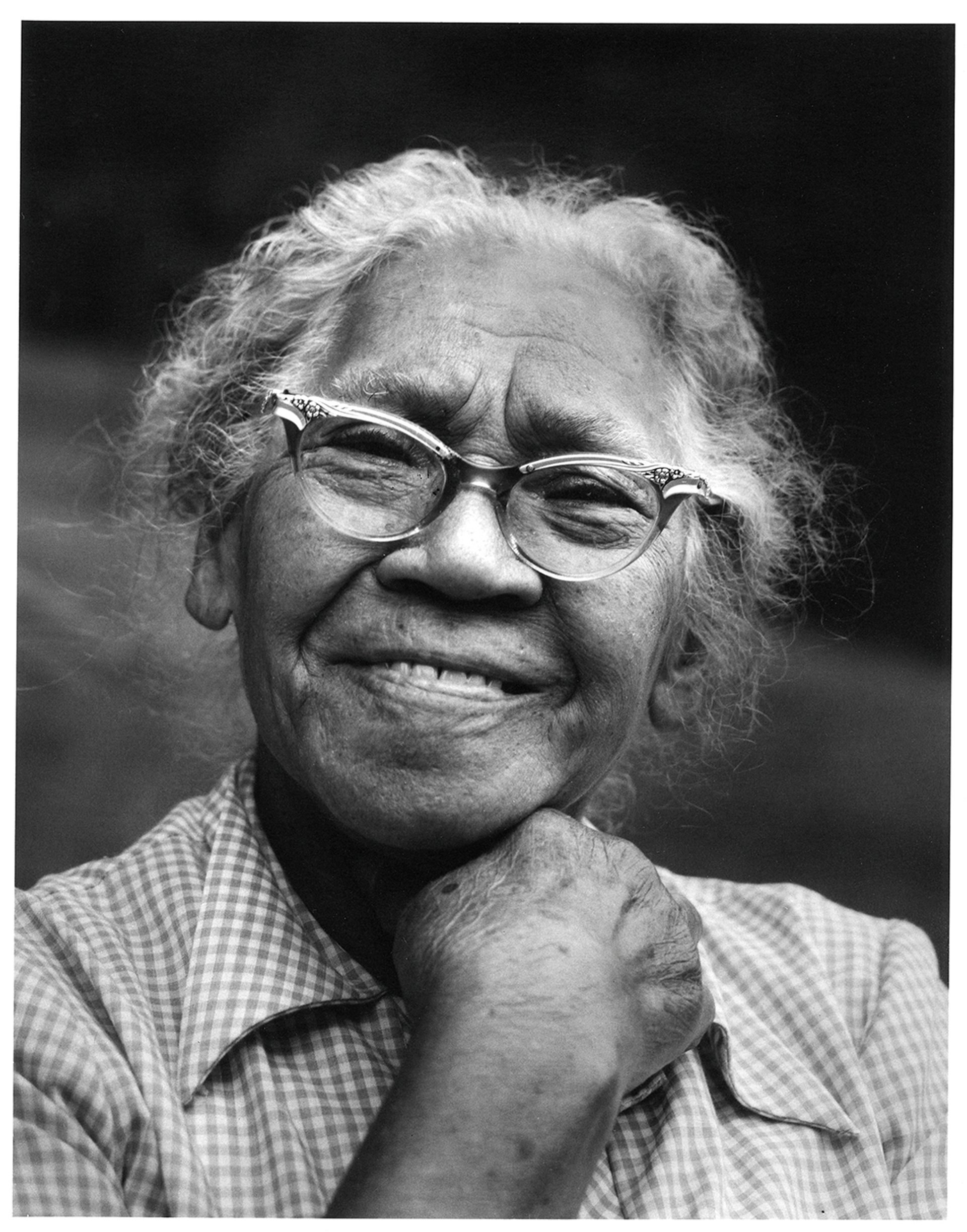

Sally Mann’s image of Gee-Gee, the housekeeper who played a key part in her childhood © Sally Mann

The painter, sculptor and photographer Cy Twombly (1928-2011)—whose studio Mann photographed—lived and worked in her hometown, and it was his presence in Lexington that gave her the confidence to stay there and not move to New York. Indeed, the deep connection that Mann has with the South is the glue that holds this book together. Slavery has inevitably cast a long shadow over this part of America, and it is Mann’s passages addressing race dynamics and her own family’s complicity in the Jim Crow system of enforced racial segregation that are among the book’s most poignant moments. A standout chapter focuses on Gee-Gee, the African American housekeeper who practically raised her. How was it, Mann now wonders, that she never questioned why Gee-Gee could not accompany her family to restaurants, or the grocery store? And where did she buy her uniforms or shoes? “What were any of us thinking?” she writes. “Why did we never ask the questions? That’s the mystery of it—our blindness and our silence.”

One dodo after another

Failure is acknowledged as part of Mann’s process and she includes many descriptions of her dogged struggles to attain the perfect shot: “I soldier on, taking one dodo of a picture after another, enticed by just enough promising ones to keep going.” However, readers expecting detailed insights into her photographic techniques (such as her favoured wet-plate collodion process that gives her images “the appearance of having been torn from time itself”), or, indeed, her path to success as a woman in the art world, will be disappointed. Large portions of the book are instead dedicated to her family history investigations, which at times feel as if we are learning more about her sexually adventurous and millionaire industrialist forebears than herself. Her thoughtful musings on the nature of photography provide some welcome glimpses into her psyche, though we are still left wondering what it is that really makes this artist tick. As memoirs go, Mann’s is as intriguing as the best of her photographs.

• Hold Still: A Memoir with Photographs, Sally Mann, Penguin Design Classics, 592pp, £14.99 (pb)