Rose Boyt’s new book, Naked Portrait: A Memoir of Lucian Freud, takes its name from a beautiful, bold, brash painting by her father Lucian Freud. It shows the writer lying on her back on a sofa, arms raised up by her head, legs parted. She is not wearing any clothes, her only covering a rumpled piece of cloth artfully arranged around her left calf and right set of toes like a bedsheet kicked off during sleep. Her limbs ripple with muscles and extend like sturdy roots across the canvas. With one hand, she shields her eyes—“from the light”, she says.

Boyt has recently finished recording the audiobook, which had her zigzagging between nervous laughter and tears. What she initially envisaged as “a quiet book about sitting” has evolved into a candid account of her knotty relationship with Freud and what it means to be the child (or, in this case, one of very many children) of a great artist. After he died in 2011, she discovered a diary she kept between 1989 and 1990, and was shocked both by what she had written and left out. “Because I was so worshipful, I didn’t question what he said, which was a bit like being brainwashed, I suppose,” Boyt says. “I’d invested so much in seeing things a certain way, without ambiguity, and I made a decision to go back and think about what really happened.”

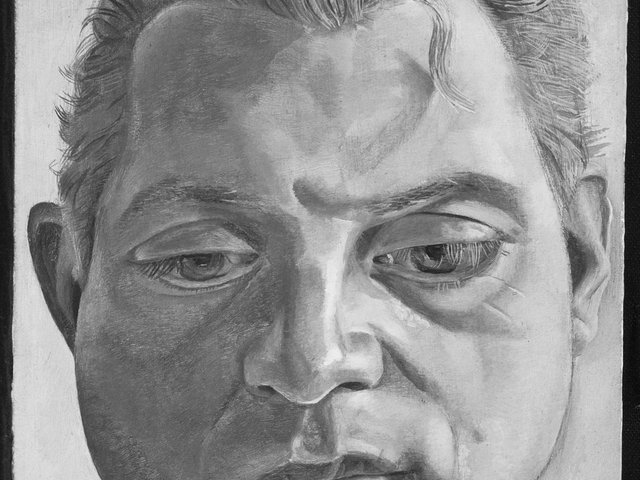

Rose (1977-78) depicts Boyt as a teenager: “Nothing had been discussed; I just assumed I would be naked” © Lucian Freud Archive; All Rights Reserved 2024/Bridgeman Images

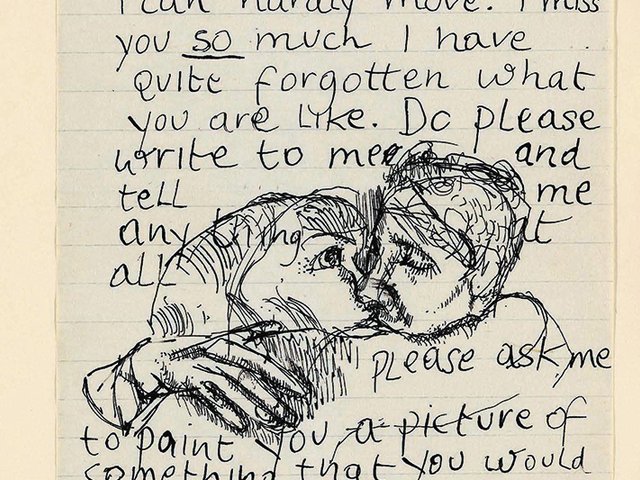

The result—a mix of diary entries and personal reflection—is as much a reckoning with her past self as his. The book begins with her experience of posing for that naked portrait, Rose (1977-78), which Freud was planning to call The Artist’s Daughter until she pointed out that it might make people think about incest. “Nothing had been discussed,” she writes, “I just assumed I would be naked.” Freud painted her from above, giving us a full-frontal view. She recalls him checking if she was happy with the pose she had chosen and the level of exposure she had inflicted on herself. Boyt writes: “I think I understand now he wanted my permission to use what he could see, to shift the responsibility onto me and take advantage of my generosity, even if I didn’t know what I was doing, didn’t know what he was asking for.”

At the time, Boyt says, she did not think about the power imbalance at play—even though she was a naked teenage girl, he a fully clothed grown man. “I was just so thrilled and enthralled by him and his life and work,” she says, with what sounds like a smile. “I loved him and trusted him to make me be me. Obviously, in hindsight, I can see that it’s his way of seeing me, but back then I felt that he was accepting my version of myself: I wanted to look angry and punky and strong, disobedient rather than submissive, and I think I do, like I’m prepared to jump up at any moment and storm out of the studio.”

Of course, she never did storm out, because that was not a part of the deal. “He was in control, and you as the sitter had to do what he wanted, which was to come when he called, to never be late or unreliable, never get a suntan,” she says. “I don’t think that was particularly awful of him; it was the only way he was going to be able to do what he needed.” Though she makes a point of avoiding other people’s accounts of sitting for her father out of self-preservation—“I don’t want to hear horrible things, or stories about his sex life”—she believes her experience was fairly typical.

Naked Portrait: A Memoir of Lucian Freud by Rose Boyt

Boyt describes in the book how Freud always wanted to work for longer than she did, and how she did not know how to make him stop, to stick up for herself. How he was generous with handouts when he felt like it, but failed to give her regular wages, meaning she was dependent on him and his mood swings. “He controlled the terms and conditions,” she writes. “That was the arrangement between us.” When things were good, he talked of his love of literature and poetry, regaling her with anecdotes and opinions. When things were bad, he would stab himself in the leg with the end of his paintbrush. He gave her port and pills, and slept with more than one of her friends. Throughout, she was respectful, patient.

Which is not to say that she did not feel conflicted. A sample of the adjectives she uses in the book to describe how she felt about sitting at the time: exhilarated, outraged, honoured, steamrollered and delighted. “I recognised his genius, so I was very much a willing participant in being there and helping him make something important,” she says. “I believed in it, and I still do believe in it.” But where once there was what she calls “absolute worshipfulness”, now there is something more slippery. “As I grew up, I realised it was possible to love and also be angry.”

• Rose Boyt, Naked Portrait: A Memoir of Lucian Freud, Picador, 416pp, £22 (hb)