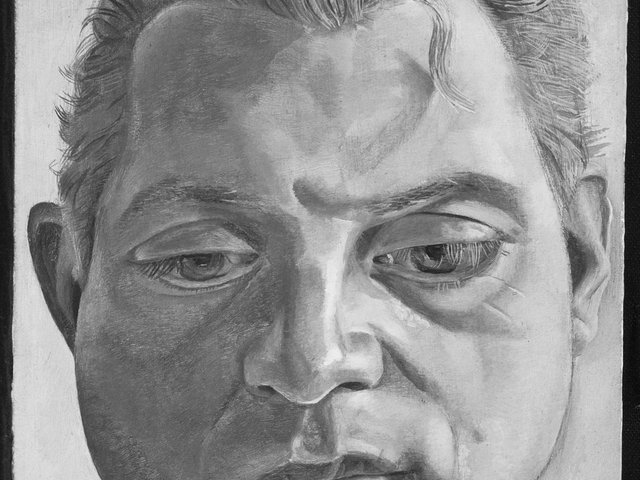

The British artist Lucian Freud (1922-2011) was famously private—he communicated mostly by phone but rarely gave out his number, which he changed often—so the task of cajoling him to agree to the investigative demands of a catalogue raisonné proved challenging.

While the artist was amenable to helping piece together his works in chronological order, he had little desire to construct an archive in his own lifetime. “I don’t want to look behind,” he once told the art historian and Freud expert Catherine Lampert, “I want to look ahead.” Freud pulled the rug from under the first effort towards the realisation of the catalogue raisonné project in 2005 but offered Lampert his blessing to edit the book posthumously.

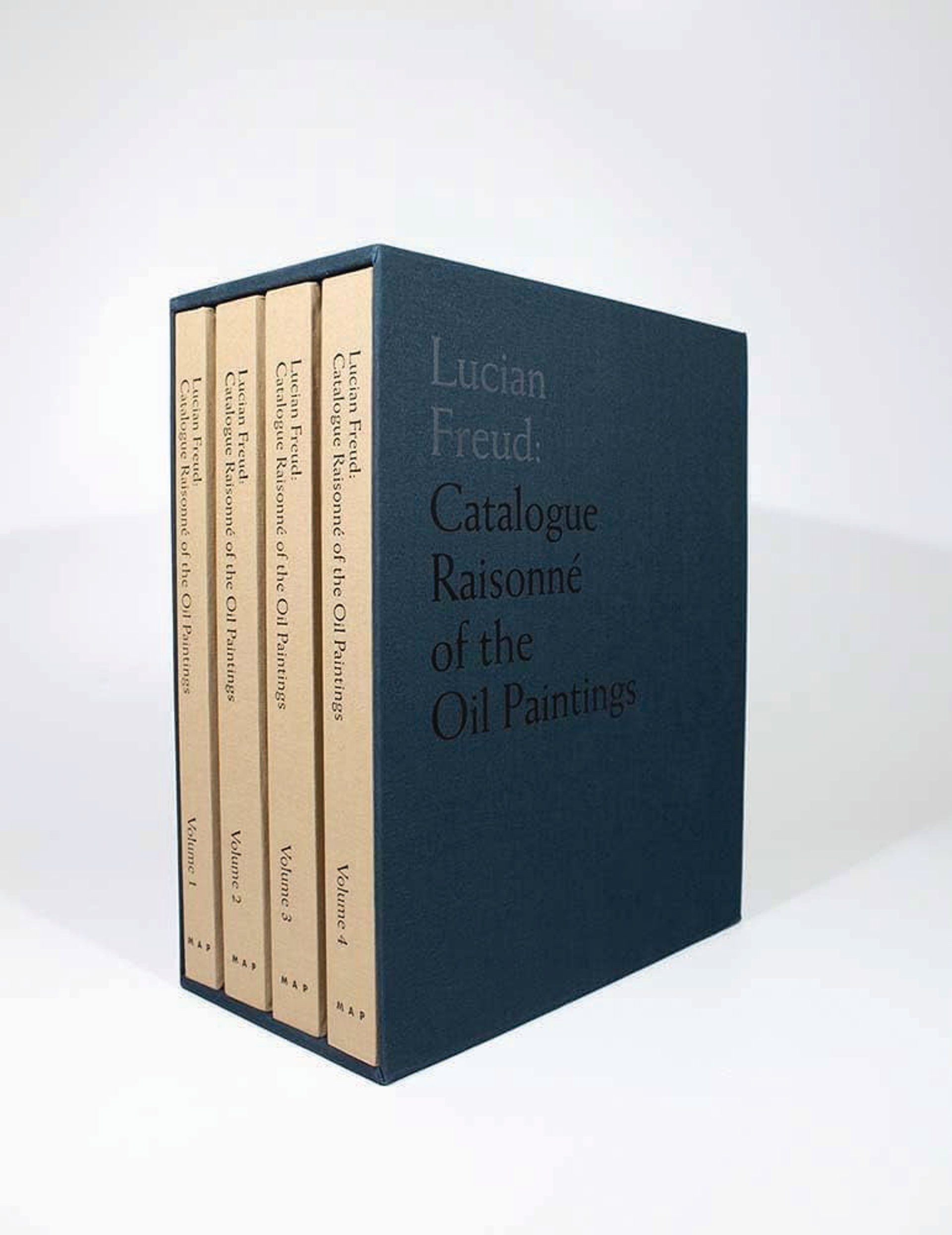

Now, 14 years after his death, the catalogue raisonné of Freud’s oil paintings has been published. Co-authored by Lampert and the art historian Toby Treves, Lucian Freud: Catalogue Raisonné of the Oil Paintings is a formidable four-volume compendium covering well over a thousand pages, with each hardback volume held in a canvas covering and all housed together in an elegant royal blue slipcase. It was David Dawson, Freud’s assistant and director of his archive, who chose Modern Art Press as the publisher, which was run at the time by Treves.

The 1,200-page catalogue raisonné for Freud includes 507 paintings, including the early Surrealist 1944 work The Painter’s Room © Lucian Freud Archive

The first volume features an excellent quintet of thematic essays, including a fascinating account of Freud’s materials by Jacob Simon; an eagle-eyed reading by Treves of Brassaï’s photograph of the artist and his second wife Lady Caroline Blackwood in Paris, which also touches on Freud’s fantastical The Painter’s Room (1944), from his short-lived Surrealist period; and Lampert’s essay on sculpture, a “first and last love” of Freud’s, especially in relation to his favourite sculptor, Auguste Rodin.

The scale of scholarly research that has gone into producing this catalogue raisonné is rare. Lampert saw all but 47 of the 507 works in the flesh, scrutinising the framing and where possible the verso of pieces up close for clues of provenance. She even tracked down the worn-out shutters featured in the breakthrough Man with a Thistle (Self-Portrait) (1946) in Poros, Greece, where Freud, already gaining an international reputation in his mid-20s, was then painting alongside John Craxton. Using the “bible”—a roving archive of sources put together by Freud’s agent James Kirkman—as well as sales books from the Hanover Gallery, the authors tracked down furtive paintings. The enterprise was hampered by the fact that Freud made a habit of selling off his pictures for fast cash to friends or to settle gambling debts.

The fraught authentication processes of Freud’s canvases—and the lengths the artist would go to retrieve old darlings—has become the stuff of legend. He would encourage stories that he put heavies to work on retrieving old paintings that he regretted letting out of his studio. According to one such story, one of Freud’s daughters, Rose Boyt, prevaricated over sending her father a painting for authentication because she was terrified that he would smash it up instead. Fans of the BBC TV series Fake or Fortune? will be delighted, then, to discover that a formerly contested portrait of a young man with a black scarf, from Freud’s student period at the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing, has now been authenticated. (Treves had disputed the piece in 2017 on account of being unable to trust “the most fallible of faculties, memory”—including Freud’s). When the painting is viewed alongside Freud’s portrait of Cedric Morris, his formative early teacher, it is clear that the two faces were made by the same hand.

Freud's Girl with Beret (1951-52) © Lucian Freud Archive

However, other contested works have not been included, among them a naturalistic portrait of a naked man bought by a north African collector for less than SFr 100,000 in 1997 ($145,000 at the time). Freud allegedly found the collector’s number on eBay and offered him double what he had paid to have it returned. On the authenticity of that work, William Feaver, Freud’s biographer, was categorical: “There’s nothing like it in Lucian’s work ever, anywhere, to survive … Every single certifiable one is fundamentally quite different from this rather careful, painstaking, correct thing.” Looking at that painting, it is clearly not a Freud.

Another test for the authors is over the question of “unfinished” paintings, as well as the artist’s process of making three or four attempts for each finished picture, before ensuring that the abandoned efforts were “destroyed destroyed”, according to Lampert. A compelling unfinished work, Head of a Man (around 1956), of the physicist and mathematician Peter Burton, which had not been published nor exhibited previously, has been catalogued. The expressive brushwork resembles Freud’s second portrait of Francis Bacon, his next painting in sequence, which was also unfinished (probably because Bacon found sitting to be excruciatingly boring). “Years later, in need of money to repay a debt,” Lampert explains in the accompanying notes to the aborted Bacon picture, “Freud sold the painting to the art dealer William Darby but then immediately lost the £600 he had received in a betting shop.”

Freud's Naked Man, Back View (1991-92) © Lucian Freud Archive

Commissioned by Time magazine in 1960, a portrait in profile of the Swedish director Ingmar Bergman was also left uncompleted, partly after Bergman refused to sit on Freud’s final day in Stockholm, and partly because Freud resented the idea of having one of his works reproduced and reprinted in the millions. “I did something which was only what a hack does and I was treated like one,” Freud said much later, after Time had fulfilled the terms of the contract but paid only half the fee on account of the portrait going unfinished. Freud gave the abandoned work to the esteemed radiologist Oliver Scott as part of his repayment of a debt.

Freud resisted the kind of forensic scrutiny of his own life and work that he demanded of his sitters. He was committed, rash and possessive, all of which fed his notoriety. This catalogue raisonné, with its near-faultless execution of forensic scrutiny, is the closest look we may ever get at this most controversial, and most brilliant, of post-war British painters.

• Catherine Lampert and Toby Treves, Lucian Freud: Catalogue Raisonné of the Oil Paintings, Modern Art Press, 1,200pp, 566 illustrations, £500 (hb)