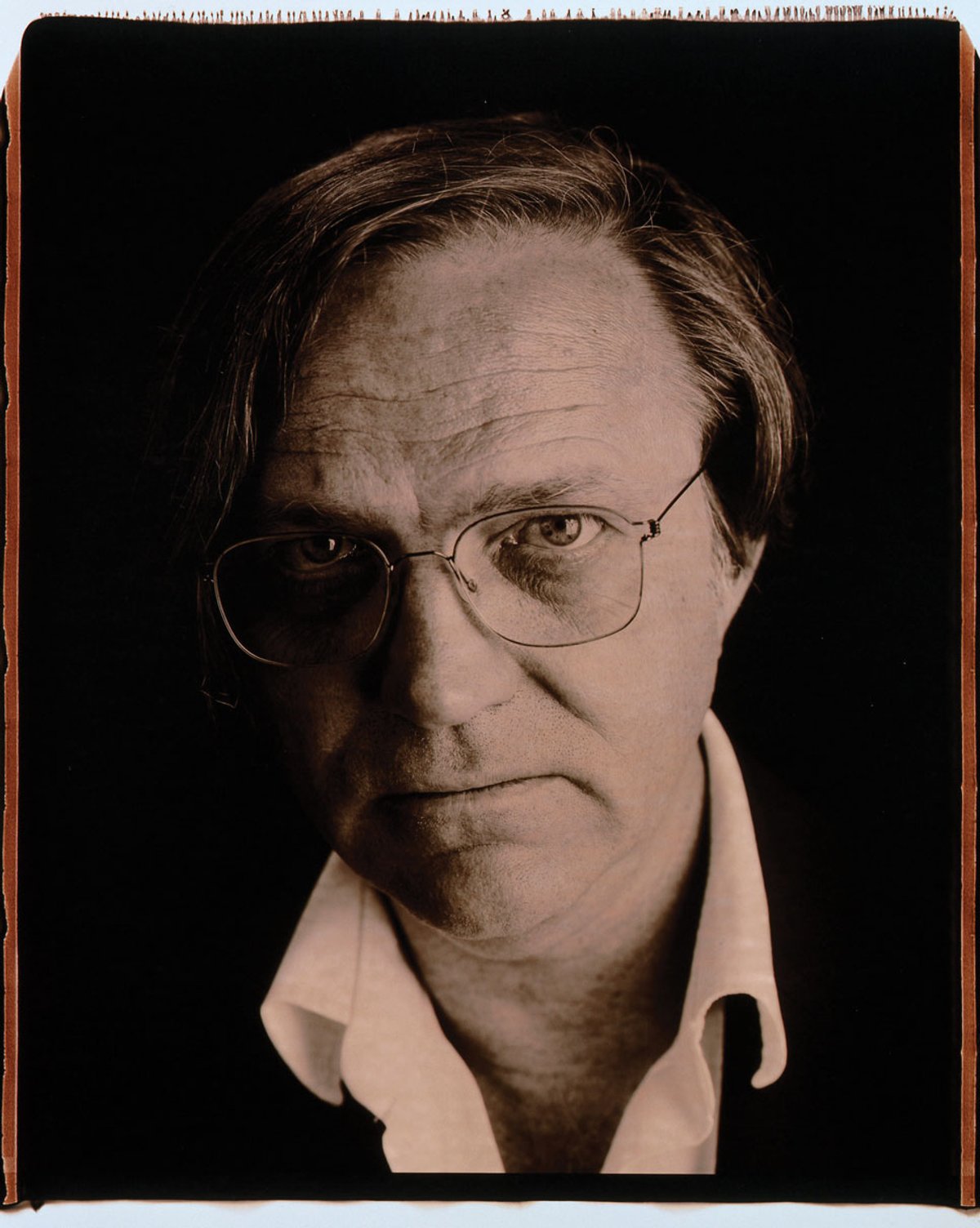

A new series called Focal Points, which offers fresh takes on Modern and contemporary art, launches this month with three volumes of essays and articles by the US art critic and curator Robert Storr. The first two bring together pieces on Bruce Nauman and Ad Reinhardt, while the third republishes a 1994 essay about identity, multiculturalism and racial division. Here, the former Venice Biennale and Museum of Modern Art curator tells us all about the new books.

The Art Newspaper: Was it challenging or gratifying to return to your 1994 essay, Between a Rock and a Hard Place?

Robert Storr: It was a bit unsettling to go back to that essay because so much has happened since I wrote it and, at the same time, so little. The whole of Trumptime has been about turning back the clock on the liberal era and its accomplishments, even on acknowledging that the United States thrived in part on slave labour notwithstanding the fact that slavery was largely confined to the South. The wealth created by means of not paying labourers in the slave states underwrote fortunes and enterprises that survive until today. Reconstruction made matters worse in many ways by promising but never fully delivering true racial equality.

Those who like to call themselves “conservatives”, but are better understood as outright reactionaries, want to strip away all vestiges of liberal judicial reform and economic melioration and make the country safe for White Supremacy. That is the current background for the institutional course correction I was trying to foster in that essay. But as Martin Luther King Jr made painfully clear, getting to the Promised Land or remaking ourselves as such a nation is still a dream deferred.

How does the essay resonate with today’s cultural debates?

We’ve been through a mind-bending period when “getting it right” in terms of social justice has been reduced to “saying it right”, and cancelling those who “say it wrong”—thereby ending all chances for communication. But the source of our plight does not primarily lie in word choice but in how one deploys social and economic capital. Speaking plainly and spending generously on programmes that will truly afford “others” the opportunities they have been denied historically will do far more good than “politically correct” speech.

You describe how the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York has become more diverse but that it took time. Did this delay frustrate you?

I was frustrated by the resistance some of my initiatives met with. After all, my job was to bring first-rate art to the attention of the general public and I was thwarted numerous times because of the formal or content-driven squeamishness of patrons who served as the gatekeepers. Some who were very liberal but schooled in Greenbergian verities baulked at the stylistics of the work I was proposing, others objected to the presumed “message” of that work. But figuration was widespread in the African-American art community as well as the Hispanic.

As for messages, I can understand how patrons squirm at being told or shown how they’ve been remiss or blind or biased. But, as the arbiters of a public trust they should rise above their personal discomfort and so acknowledge that they’ve gotten the message.

• Focal Points series, Robert Storr, Francesca Pietropaolo (ed), Heni Publishing: Vol. 1, Focal Points: Bruce Nauman, 152pp, £19.99 (hb); Vol.2, Focal Points: Ad Reinhardt, 140pp, £19.99 (hb); Vol. 3, Focal Points: Between a Rock and a Hard Place, 128pp,£19.99 (hb)