A new publication on the life and work of the American-Canadian artist Philip Guston, by his daughter Musa Mayer, is published in the wake of the furore late last year over the delayed touring survey of Guston’s works. The book arcs from Guston’s time as a muralist working with the government-funded Federal Art Project in the 1930s to his return to figuration in the 1960s when he reintroduced hooded Klansmen to his paintings, which were at the centre of last year’s controversies. A selection of rare biographical photographs and more than 120 illustrations of Guston’s paintings and drawings accompany Mayer’s exploration of her father’s artistic innovations.

Musa Mayer

The Art Newspaper: Why is the book important from a scholarly point of view?

Musa Mayer: Unlike the definitive Rob Storr monograph Philip Guston: A Life Spent Painting (2020), which is exhaustively documented, my small volume is intended as an affordable but concise introduction to the life and work of Philip Guston, with limited, although accurate, text and an abundance of high-quality images. Its intended readership will be those curious viewers who are unfamiliar with the artist’s life and work, although they may have seen individual paintings or drawings reproduced, especially recently with the intense controversy about the hooded figures of 1968-70 and the postponement of the retrospective [Philip Guston Now]. The goal is to offer a sense of Guston’s whole life as it unfolded, as well as the full 50-year scope of his work.

How challenging and satisfying was it to revisit your father’s work and life?

For the past five years since my retirement from breast cancer advocacy, I’ve focused exclusively on the legacy work of the Guston Foundation, most recently the launch of our website and catalogue raisonné at PhilipGuston.org. In addition, I’ve curated a number of exhibitions for Hauser & Wirth, edited an award-winning book, entitled Philip Guston’s Nixon Drawings: 1971 and 1975, and wrote an extensive catalogue essay for Resilience: Philip Guston in 1971. With our foundation staff, I was also intensely involved with the preparation of the Rob Storr book, which was years in the making.

It’s fair to say, however, that the most challenging confrontation with my father’s life and work came years earlier when as a young woman in the Columbia MFA programme in Writing, I worked on my memoir, Night Studio, first published in 1988, and republished in 2016 in a fully illustrated edition.

So, I was fully immersed in my father’s work and life already when I began this introductory book. I found selecting the work to be reproduced and laying it out, and distilling commentary on his life and work into a brief three-part text a real writer’s challenge in terms of achieving the necessary concision while retaining a sense of the richness and diversity of the work.

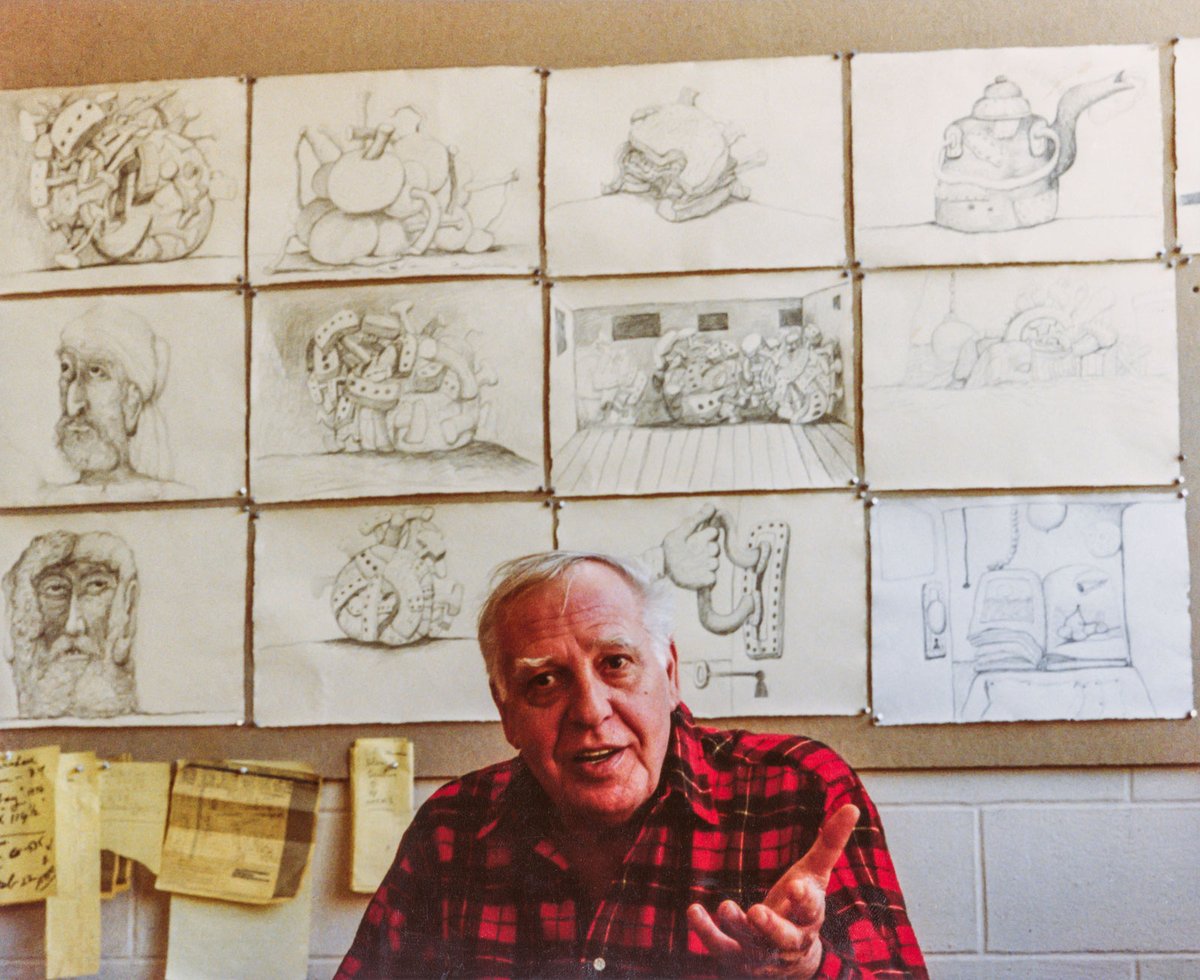

Guston painting his mural Work the American Way (1939) © The Estate of Philip Guston

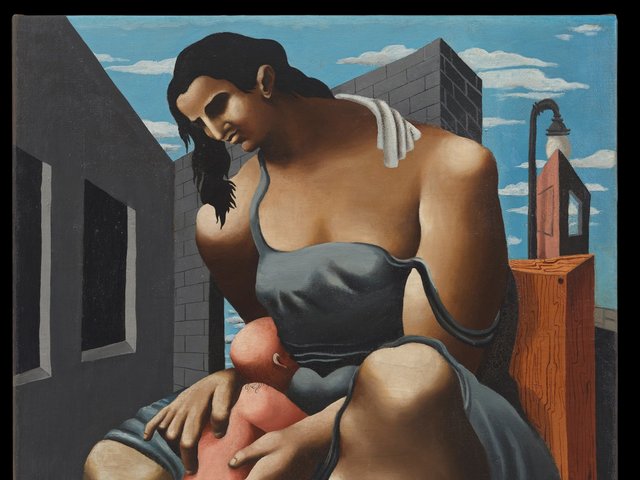

The early figurative works such as Bombardment (1937) are not widely known—is there much documentation on these early pieces?

Most people are unaware of my father’s earliest works, particularly the murals. There is still much archival work to be done to adequately document these pieces. Some are, sadly, lost, with little or no information, but Bombardment, most recently in the Vida Americana show at the Whitney, is well known and documented. It is the intention of The Guston Foundation to facilitate the conservation of the great mural in Morelia [The Inquisition, 1935]. Our website can reveal more on these early works.

Guston's abstract painting For M. (1955) © The Estate of Philip Guston

Guston's career is marked by turning points and reinventions. Is it fair to say that the main crossroads in his career came in the late 1940s with a transition to abstraction (as seen in The Tormentors, 1947) and then in the late 1960s when he felt frustrated at the world and switched back to figuration?

Yes, that’s a fair characterisation, although personally I see the changes as more evolutionary than as reinventions. I believe that the great power of the late work would not have been possible without his profound involvement with the process of painting itself, acquired between 1950 and 1965 as he explored abstraction. His move back toward figuration came from an intense need, as he said, to “tell stories,” to not feel limited by the constraints of abstraction, “to paint the world as if it had never been seen before, for the first time”.

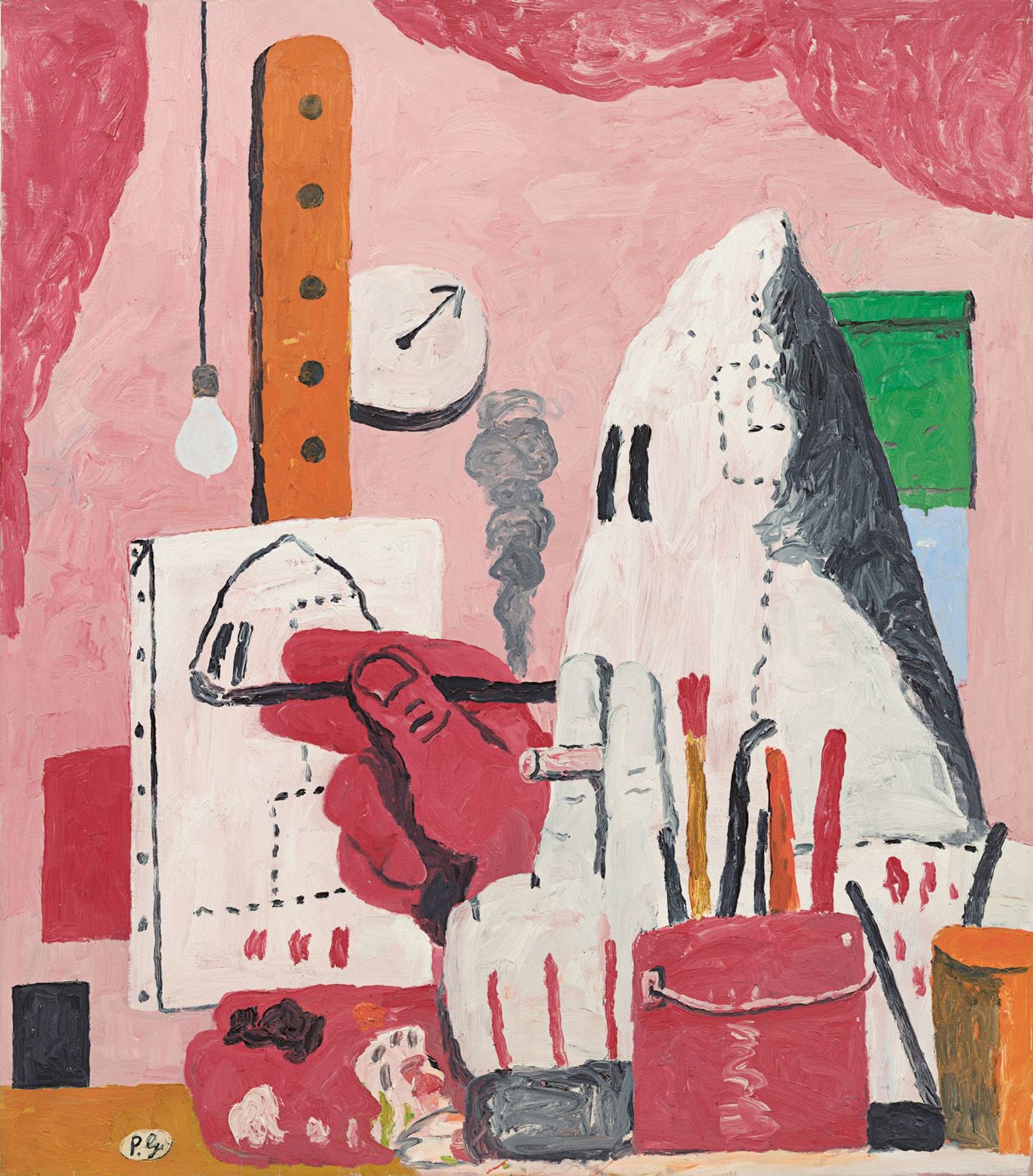

Guston's The Studio (1969) © The Estate of Philip Guston

How do you now feel about the decision to postpone the Guston retrospective, Philip Guston Now, at the National Gallery of Art in Washington and three other museums? You said last September: “The danger is not in looking at Philip Guston’s work, but in looking away”. Are you still of this opinion?

The terror and pain of racism and intolerance was an early subject of Guston’s work, as is clearly shown in my book. I know that I am not alone in feeling that the hooded figures in the late work involve a different kind of reckoning, that they offer an unvarnished view of the banality of evil, a need to see white complicity for what it is. These works were controversial when they were first shown 50 years ago; they remain controversial today, and I believe deeply relevant.

The groundwork so beautifully laid by the diverse voices in the catalogue Philip Guston Now was in a sense wasted as long as the paintings themselves are not visible. The decision to postpone the retrospective avoided a difficult but necessary dialogue, apparently based on the museum directors’ belief that these paintings would inevitably be misunderstood as racist. I agree with the many journalists and others who have written that today’s movement for social justice makes Guston newly meaningful and offers new opportunities for dialogue.

That said, I am pleased that the museums have rescheduled for 2022 and 2023. Given the increasingly uncertain future, I choose to remain hopeful that Philip Guston Now will still take place as a full retrospective, and that the public will have the opportunity to appreciate Guston for more than a misguided decision about Klan-like imagery. I hope my introductory book will help to accomplish this as well.

• Philip Guston, Musa Mayer, Laurence King Publishing, 120pp, $19.99 (pb)

• Sign up to The Art Newspaper's Book Club newsletter here