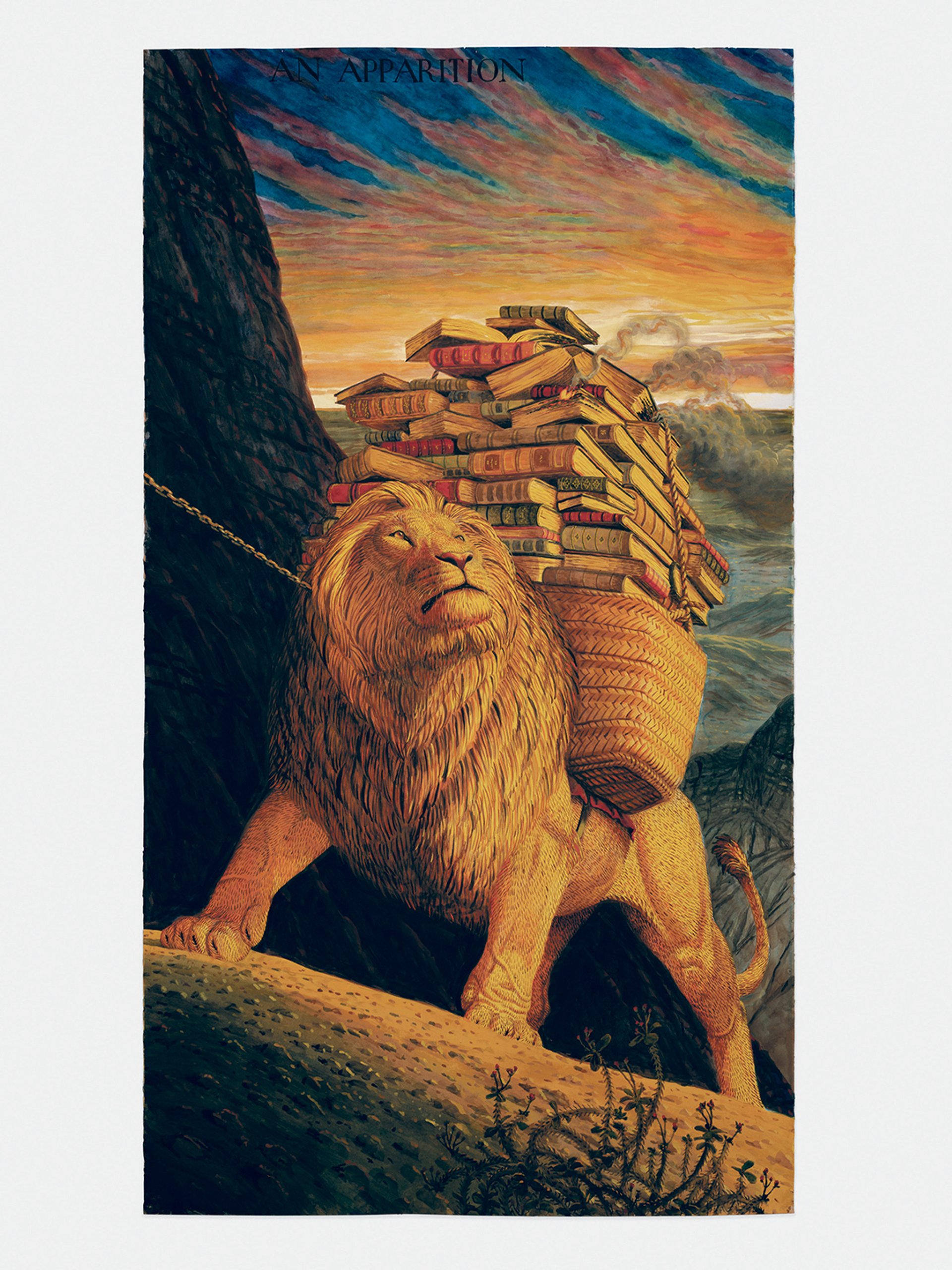

The artist Walton Ford is known for approaching the Old Master genre of animal painting with a contemporary twist, creating monumental watercolours of wildlife that are imbued with historical and literary references and humour. His exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum celebrates his gift of 63 sketches and studies to the museum, which are displayed alongside some of their respective paintings and a selection of works from the institution’s permanent collection. This coincides with an exhibition at the Ateneo Veneto in Venice organised by Kasmin Gallery, in which Ford has created works inspired by Tintoretto’s Apparizione della Vergine a San Girolamo (around 1580) and other masterworks.

An Apparition (2024) is inspired by Tintoretto’s Apparizione della Vergine a San Girolamo (around 1580) from the Morgan’s collection Photo: Charlie Rubin; © Walton Ford

The Art Newspaper: What resonated with you about the Morgan’s collection?

Walton Ford: What’s most exciting is their collection of ephemera. I’ve been making large-scale watercolours for decades, and each had studies that went into their making. These were working drawings and watercolours that wound up on the studio floor covered in footprints or were thrown into boxes. I didn’t think there was value in them, except informational value. Working with [the show’s co-curator] Isabelle Dervaux, I became more comfortable with the idea that these things littering the studio floor were worth sharing and that people might be interested in knowing how I work. It seemed like hubris at first. But the moment that an artist is inspired and crafts the inspiration is a charged moment. It’s like experiencing love at first sight. It can’t be replaced, sometimes even in the finished piece.

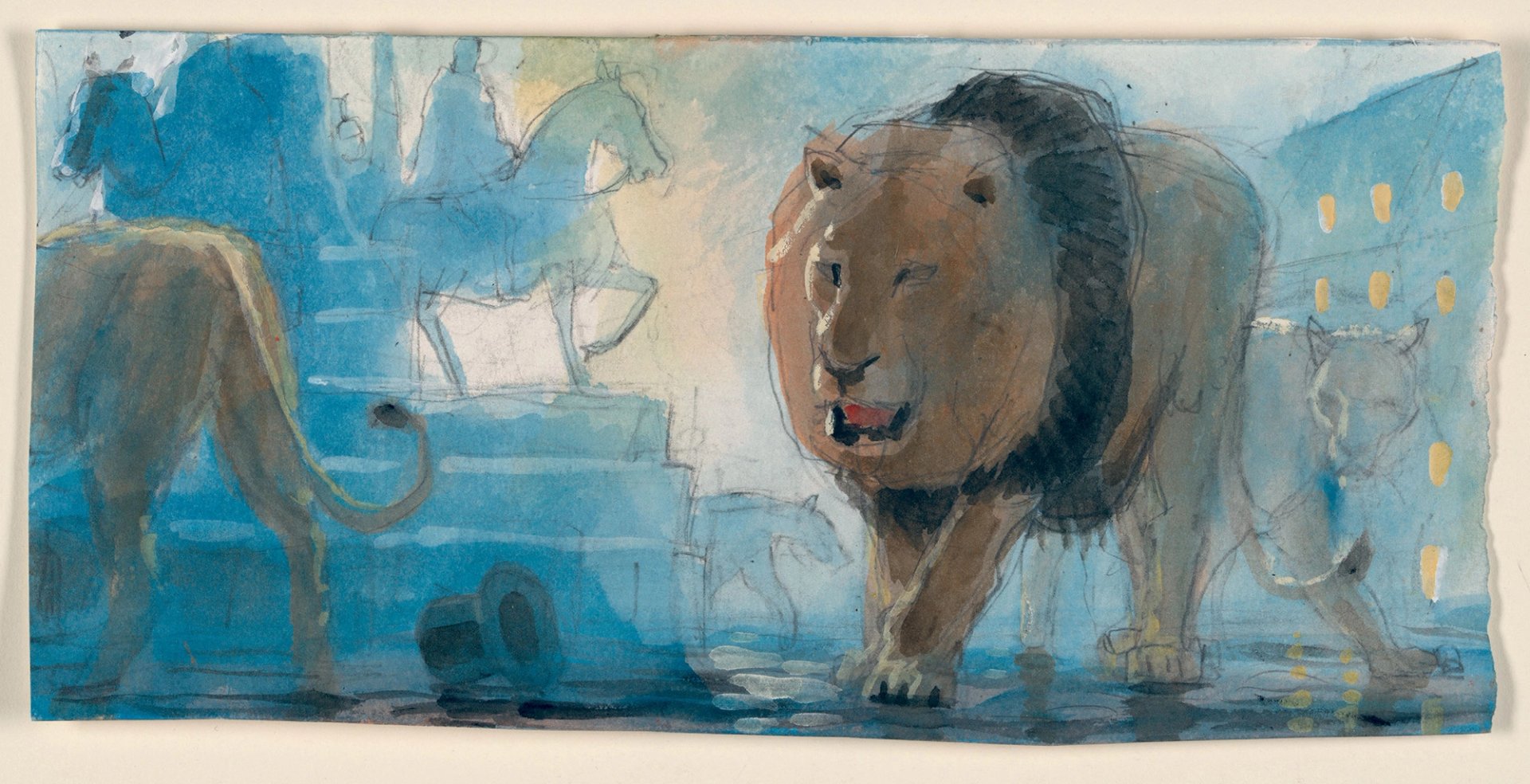

What can viewers learn about your process through these works?

It could be imagined that a realist artist like me, who is interested in details and keen observation, would be tight or constrained. But the fact is that these studies are gestural, loose and expressive. That’s where the animal lives. What I’m doing much later in the process is attempting to retain as much of that freshness as possible. For the earliest paintings, I would scour through boxes full of images at the Picture Collection of the New York Public Library and the Bettmann Archive. But it’s just one angle of the animal, making it difficult to understand the structure. You might not be able to see how the fur grows in certain areas, for example. Two-dimensional resources are limited, so I’ll take their pictorial tropes and use them in the work. Animal dioramas—like the lion diorama in the American Museum of Natural History—have been good three-dimensional references for me.

Your work is often derived from literature. Which books have made an impact on you?

In her diaries, Virginia Woolf writes that she saw two foxes on her 48th birthday. One was running in the rain, and the other was barking in the sun. I made a painting that was about her mental illness, because it felt like a powerful metaphor. Which is more dangerous? The one running in the rain looks calmer but might be depressed; the one barking in the sun is manic. There is also a phrase from Oskar Kokoschka, where he talks about painting a mandrill in the zoo and says that the mandrill loathed him. I thought that was so telling about an artist’s self-absorption—to think that the mandrill had a grudge against him or even cared. The mandrill has a grumpy expression on his face, reflecting Kokoschka’s own super-hubristic insecurities and need for reassurance. “I brought him a banana every day, and he still hated me,” he said.

Study for “Siegesdenkmal” (2019) is among the 63 studies and drawings that Walton has gifted to the Morgan © 2023 Walton Ford

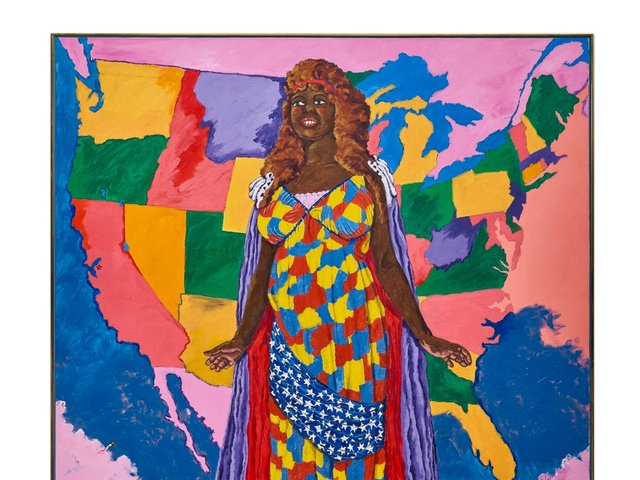

Several of the studies show lions. What does the motif symbolise in your work, like in Ars Gratia Artis (2017)?

Luckily this work was included, because it’s a very important one of mine. I did a show at Gagosian in Beverly Hills in 2017 that was entirely about California, which has an incredible natural history starting with the settlers and spanning over 500 years until Hollywood. I wanted to mix the two and started researching the MGM lion. Over time, MGM had to refilm the lion; there was a black-and-white one in the silent era, then one when colour was introduced. I thought about all these retired MGM lions. This particular MGM lion is lounging by a swimming pool, and there’s a party atmosphere that is winding down. He looks like he’s drunk or something. He’s a debauched Hollywood type thinking about the old days. The title means “art for art’s sake”, which I thought was hilarious.

The show includes several works you chose from the Morgan’s collection, from Delacroix to Audubon. What guided your selection?

The Morgan is smart to ask contemporary artists to engage with the collection, because the public, and even collectors, are uninterested in Old Masters as a general rule. It requires a tremendous amount of scholarship, and it’s so complicated and elitist that the general public will turn away. I picked 30 works, including some surprising masterpieces like Gustave Doré’s Lion Entering a Cave. At first glance, it looks like a drawing of a cave with a deep shadow. Then, in the shadows, there’s this figure of a lion going into the cave, almost like the back view of the animal. It has the immediacy of a closed-circuit TV image, or a screenshot on a camera. It has amazing movement. It’s a dream for an artist to be able to do this. Even the most self-absorbed, arrogant, insufferable artists in the contemporary art world show humility and appreciation when they are in front of a masterpiece.

• Walton Ford: Birds and Beasts of the Studio, Morgan Library & Museum, New York, until 20 October

• Walton Ford: Lion of God, Ateneo Veneto, Venice, until 22 September