MoMA PS1, until 2 September

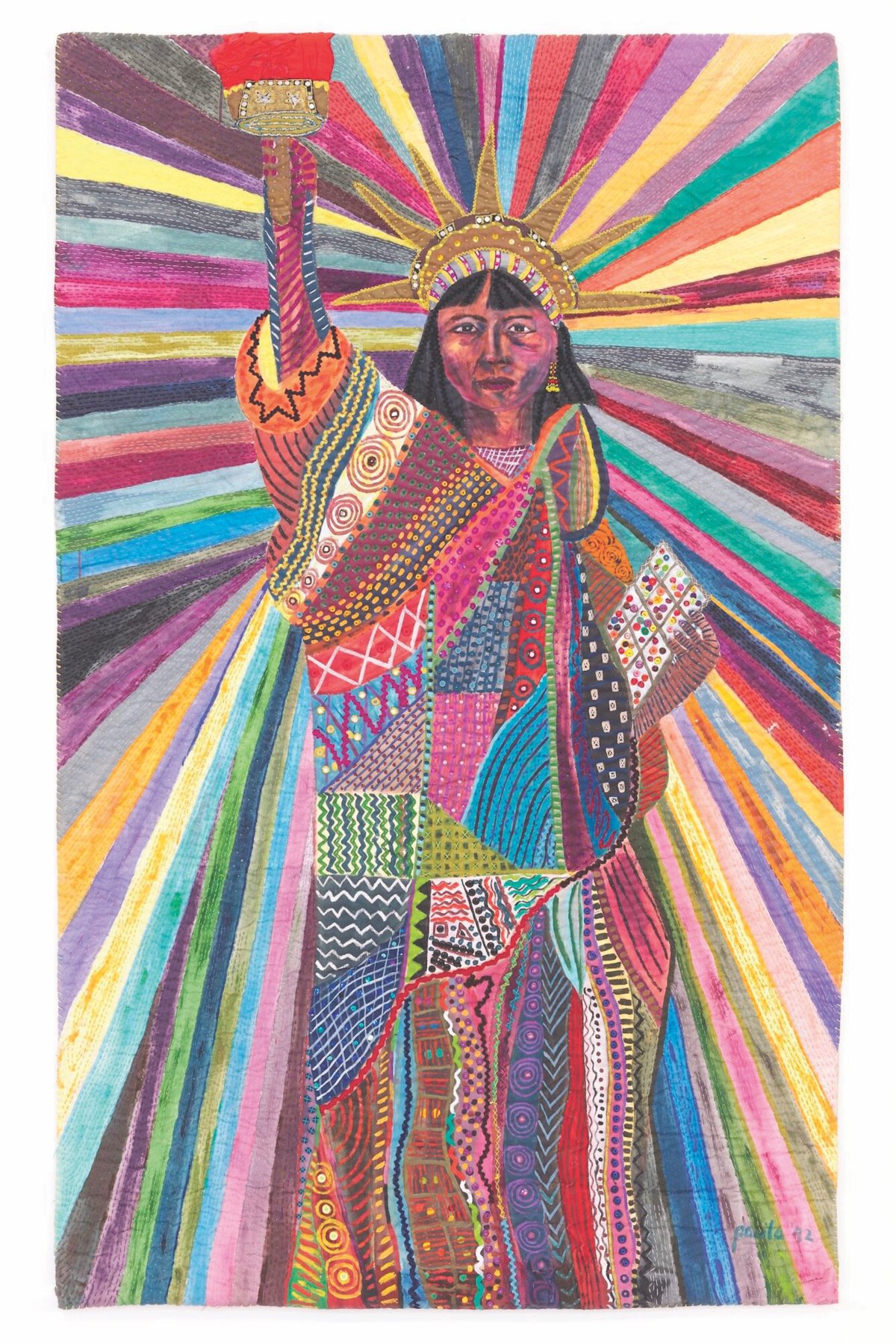

Organised by the Walker Art Center and now on view at MoMA PS1, this is the first museum retrospective of the late Filipina artist Pacita Abad (1946-2004). She is most widely known for what she referred to as “trapunto” paintings—massive works that she made by stuffing and stitching her painted canvases, instilling them with three-dimensional, quilt-like textural elements. The daughter of politicians, Abad was an activist and organiser set on pursuing her own career in politics until this trajectory was upended in 1970, when she had to flee the country due to her family’s political persecution. She went on to live across six different continents throughout her life, pulling artistic influences from each new locale and accumulating a wildly prolific body of work (of which more than 50 pieces are currently on view in the exhibition). W.L.

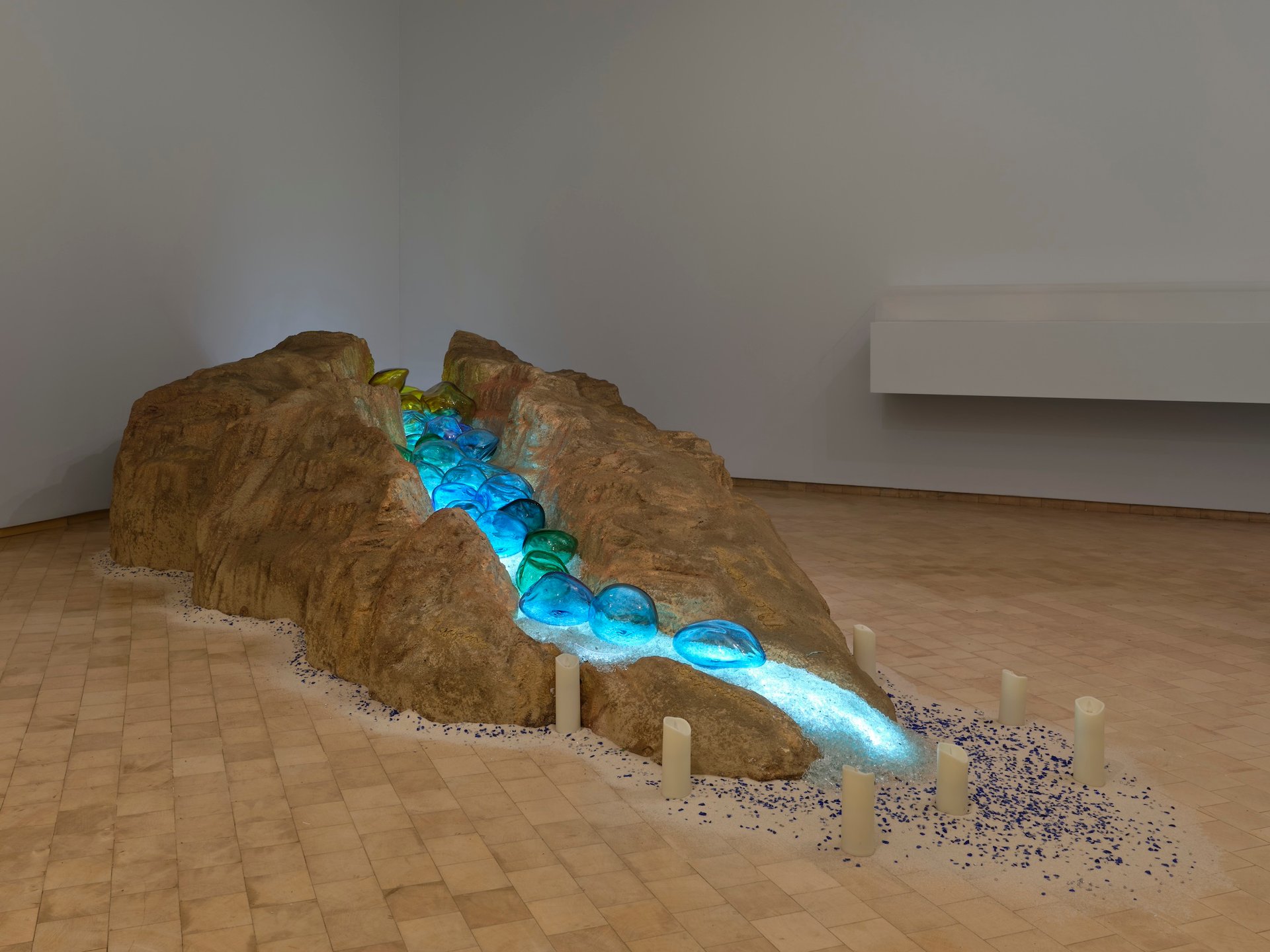

Installation view of Amalia Mesa-Bains, What the River Gave to Me, 2002. El Museo del Barrio, New York. Courtesy of the artist and Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco. Photograph by Matthew Sherman/Courtesy of El Museo del Barrio.

Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory

El Museo del Barrio, 2 May-11 August

This is the first major retrospective for Amalia Mesa-Bains, who since the 1970s has created work that uses the form of traditional Mexican altars and ofrendas (offerings to the dead) as the aesthetic and narrative driving force behind her practice. Mesa-Bains—who was born in 1943 in Santa Clara, California to a family of Mexican immigrants—has long been interested in these forms, which have evolved in her work over the decades into the large-scale installations she makes today—dazzling in their intricacy yet also intimate and personal, reflecting the mythology of her life. “Most artists are telling a story, and to some degree I think most of us are following a particular set of questions over time, and they don’t really change,” she said in a 2023 interview with the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive, which organised this exhibition, “the way we answer them changes.” W.L.

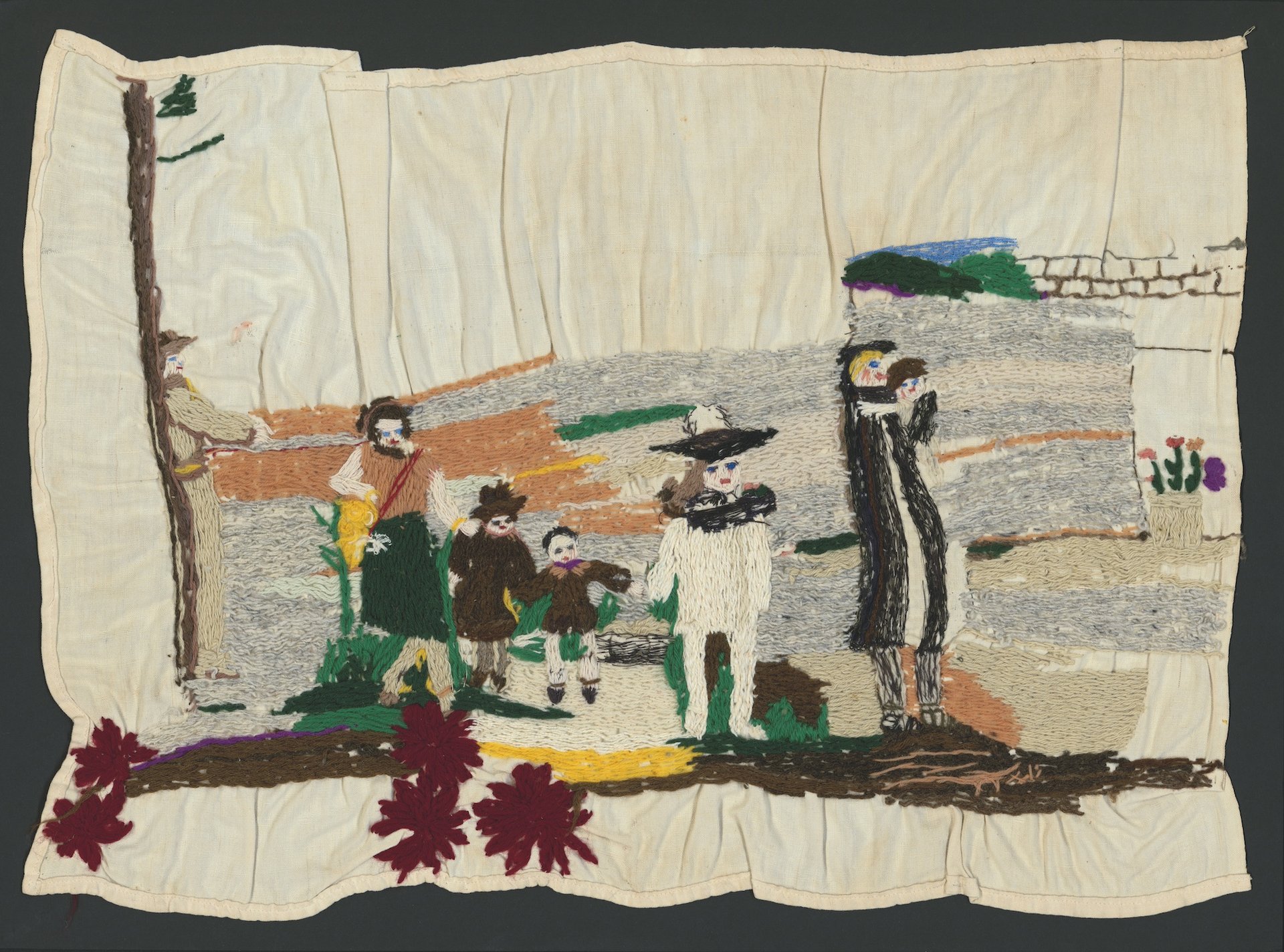

Marguerite Sirvins, Untitled (Family taking a walk in the countryside), undated. Wool embroidery on canvas (unfinished). Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne, cab-563. Photo reproduction: Giuseppe Pocetti, Atelier de numérisation – Ville de Lausanne

Francesc Tosquelles: Avant-Garde Psychiatry and the Birth of Art Brut

American Folk Art Museum, until 18 August

This exhibition explores the Catalan psychiatrist Francesc Tosquelles’s radical ideas around psychiatric care and their ensuing influence on the artistic avant-garde of the 20th century. By opening an “asylum village” at the Saint-Alban Hospital in the south of France, Tosquelles—who fled Spain during the Civil War—developed a non-hierarchical approach to psychiatric care built upon collaboration between patients, doctors and staff. Throughout the Second World War and during the German occupation of France, Tosquelles’s village became a refuge for artists and intellectual dissidents, who in turn were exposed to the art that the asylum patients were creating. In addition to exhibiting works associated with this moment in history, the show looks into the history of mental health care in the US and includes works by American artists such as Martín Ramírez, Judith Scott, Masaaki Iswasmoto, Melvin Way and Gabriel Mitchell. W.L.

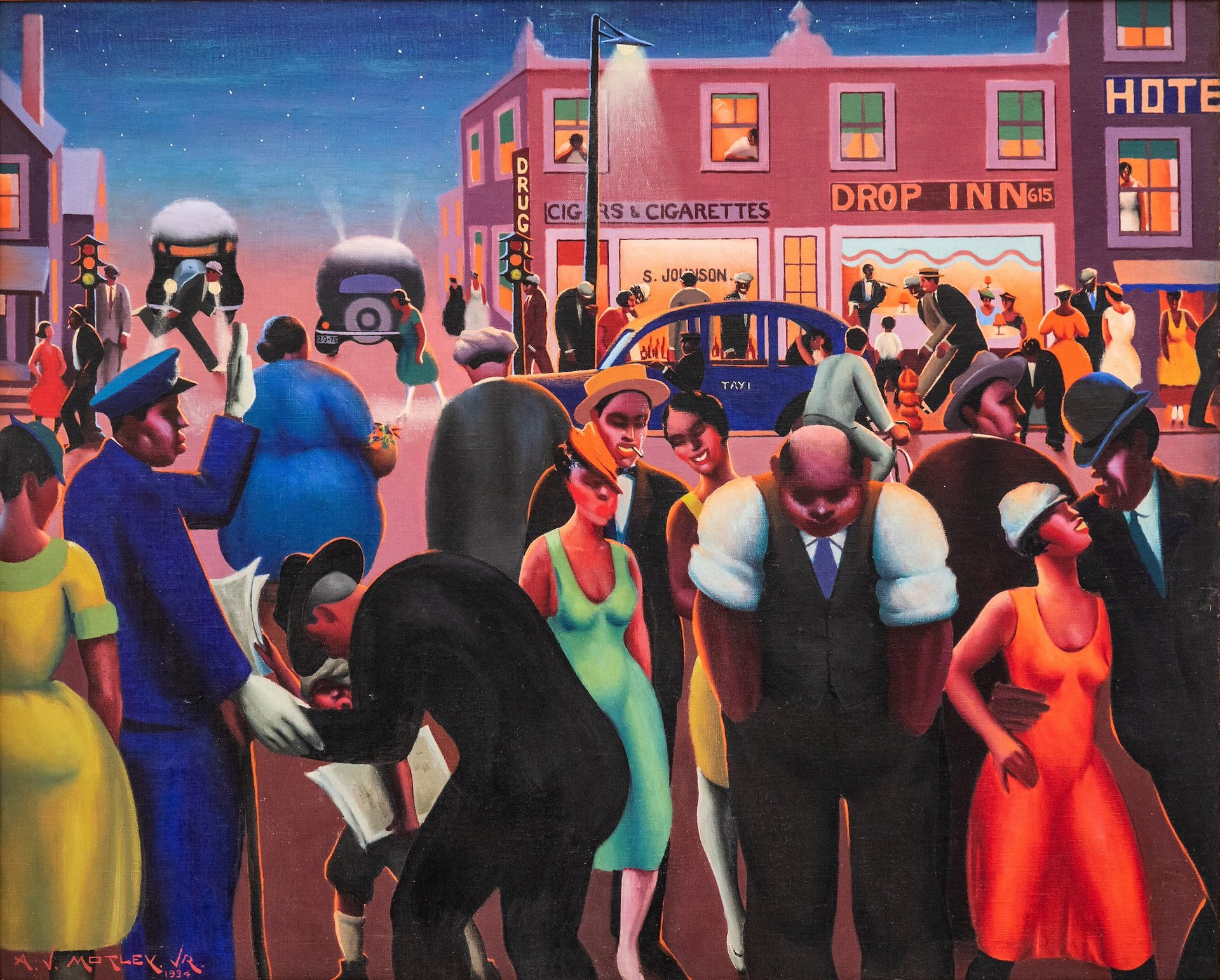

Archibald J. Motley, Jr, Black Belt, 1934. Collection of the Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Virginia. © Valerie Gerrard Browne.

The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism

Metropolitan Museum of Art, until 28 July

Only the fourth museum survey to focus on the Harlem Renaissance and the first in New York in almost four decades, The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism presents around 160 works of painting, sculpture, photography, film and more by artists including Aaron Douglas, Archibald Motley Jr, Augusta Savage and Laura Wheeler Waring. The wide range of influences and styles across the exhibited artists demonstrates how the reach of the Harlem Renaissance moved far beyond the narrow geographic focus of the term. But the Met proposes a collective narrative: of a movement that transformed modern visual expression through the portrayal of often everyday and ordinary moments in Black life. As the Met’s curator-at-large Denise Murrell, who organised the exhibition, says: “These are Black artists, photographers, painters, sculptors and filmmakers making work that represented the community—its individuals and the community as a whole—in the way that we chose to be seen.” A.M.

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land, 2016-18. Presented by Danspace Project, New York, 2018. Photo by Ian Douglas/courtesy of Danspace Project. © Joan Jonas/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Joan Jonas: Good Night Good Morning

Museum of Modern Art, until 6 July

The trailblazing octogenarian Joan Jonas’s animating career retrospective, curated by Ana Janevski, is primal exhibition-making. From start to finish it tempers an exhilarating sense of childlike wonderment at the world with the knowledge of its imperilled existence. It gives the most ephemeral and market-defying form of art—performance—a solid body.The show’s chronological, inherently thematic, organisation tracks Jonas’s evolution from her first forays into body-positive performance and rudimentary explorations of new technologies, to sophisticated, dreamlike observations of a natural world that is changing beyond recognition or disappearing altogether. In SoHo, where Jonas has lived since the early 1970s, The Drawing Center has given itself over to Animal, Vegetable, Mineral (until 2 June), a robust retrospective of the artist’s works on paper and an essential companion to the show at MoMA. L.Y.

Laura Davidson, Useful Knowledge, 1998. Boston, Massachusetts: Laura Davidson, no. 21 of 25 copies, signed by the artist. Linoleum prints, some hand-coloured, bound in painted wooden boards. Courtesy the artist

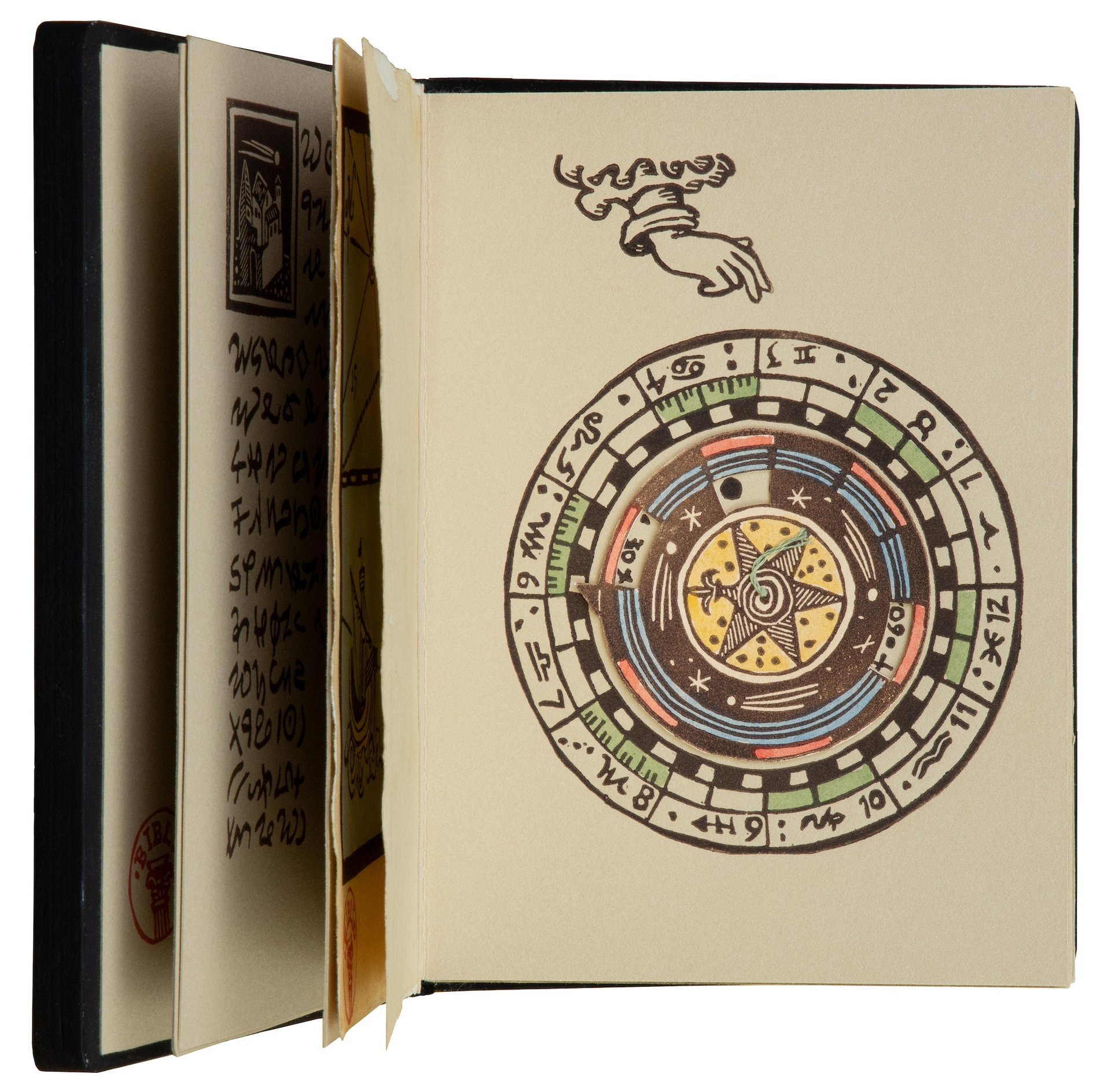

Language, Decipherment, and Translation—from Then to Now

Grolier Club, until 11 May

Deirdre Lawrence, a longtime museum librarian and book curator, organised this exhibition drawn heavily from her own collection of contemporary artists’ books. The featured tomes deal with various forms of translation, from Reconstruction Project (1984)—a collaboration spearheaded by Sabra Moore to create a kind of Mayan codex based on a 16th-century text about the conquest of the Yucatan, to a 2022 accordion book by the Indigenous artist Erin Mickelson featuring phrases based in the Oneida language. The featured artists have experimented with both the book form—including traditional bound editions, scrolls, woodcuts, embroidery, collage and sculpture—typography and language itself. In his Codex Seraphinianus (2021), for instance, the Italian artist Luigi Serafini examines coding systems across disciplines, from genetics to languages, including in “asemic”, an imaginary language he invented. B.S.

Installation view of Melissa Cody: Webbed Skies, on view at MoMA PS1 until 2 September Photo: Kris Graves

MoMA PS1, until 9 September

This is the first major museum exhibition for Melissa Cody, a fourth-generation Navajo/Diné weaver. Much of her practice is rooted in the Germantown Revival style: a type of Navajo weaving developed when weavers began to take apart the commercially dyed blankets provided to them by the US government and repurposing the fibres to create tapestries rooted in their own traditions. This style is also indicative of Cody’s work in its harmonious blend of generational practices—while Cody’s work is no doubt an offspring of ancestral tradition, her work is also a bridge towards a new generation of weavers and artists, as well as towards a large, international audience.

“I started weaving when I was five years old, and I can look back at every piece that I’ve woven and they all have their own time stamps of where I was at that time in my life, so it’s very biographical in that sense,” she says. “It has also been a personal journey of understanding my own artistic practice and critiquing it in order to develop larger bodies of work that exist around cohesive themes or explore the events of my life.” W.L.

Nona Faustine, They Tagged the Land with Trophies and Institutions from Their Rapes and Conquests, Tweed Courthouse, NYC, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Higher Pictures. © Nona Faustine

Brooklyn Museum, New York, until 7 July

When Nona Faustine learned about the history of slavery in New York, a “lid was blown off”, she says. Born and raised in Brooklyn, the photographer was familiar with the colonial names that adorn the city, but she wasn’t aware of its deep ties to slavery. “Once you know the history, you see it everywhere,” she says. “There are colonial houses owned by slave owners everywhere. All you need to do is look up the early Dutch settlers—Wyckoff, Lefferts, Van Cortlandt—their houses are still here, and there are streets and parks named after them all around the city.

As Faustine researched this history, she began photographing herself in places linked to enslavement, often posing nude apart from a pair of white “Church Lady” shoes—a nod to the use of clothing to assimilate and signify decorum. Many are familiar sites, such as Wall Street, the beacon of commerce that was named for the defensive wall built by slave labour and the site of public slave auctions between 1711 and 1762, as well as the nearby Tweed Courthouse, which was constructed along the African Burial Ground, the largest colonial-era cemetery for Africans that was rediscovered in 1991. A.K.

Peter Hujar, Drag Ball, Hotel Diplomat (I), 1968. Courtesy The Ukrainian Museum, New York. © The Peter Hujar Archive/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Ukrainian Museum, 2 May-1 September

This exhibition features three little-known bodies of early work by the Ukrainian American photographer that presage his famous images of the queer avant-garde counterculture of the 1970s and 80s on New York’s Lower East Side, near where the Ukrainian Museum now stands. It will be publicly displaying many of these images for the first time. Among them are photographs taken by Hujar at homes for disabled children in Southbury, Connecticut, and Florence, Italy that highlight the strong rapport he established with his subjects. “Somehow he had this charisma, this photographic magic where he made you feel super comfortable,” says Peter Doroshenko, the museum’s director and the show’s curator. Yet Hujar, who was raised by his grandmother on a farm in New Jersey speaking only Ukrainian, was selective about who he shared his heritage with, Doroshenko says. “With some friends he did. With others he didn’t. Once again it was that battle of trying to figure out identity.” S.K.

LuYang, DOKU – the Self (still), 2022. Single channel 4K digital video; 36 minutes Courtesy of the Artist and Jane Lombard Gallery

The Rubin Museum of Art, until 6 October

The Rubin Museum’s last exhibition at its permanent space on West 17th Street brings in 32 contemporary artists’ works, each of which relates to or is inspired by a piece in the museum’s permanent collection. For example, a beautiful and intricately painted wood-and-metal Tibetan prayer wheel from the 19th or 20th century is accompanied by the Nepalese artist Bidhata KC’s Out of Emptiness (2023), an interactive prayer wheel made of old tin cans—inspired by the vernacular prayer wheels she has seen in remote villages.

This farewell exhibition, which also marks the museum’s 20th anniversary, is interspersed across all six floors and is a joint curatorial effort between the Rubin’s curatorial director Michelle Bennett Simorella, the New York-based artist Tsewang Lhamo and Roshan Mishra, director of the museum Taragaon Next in Kathmandu, Nepal. This last curator is of particular note, given that he has been extremely vocal in calling for the restitution of works from museums—including the Rubin. In fact, it was through his restitution work that he came to be involved in this show. E.G.

Sonya Clark, Unraveling (performance view), 2015 Courtesy of the artist

Sonya Clark: We Are Each Other

Museum of Arts and Design, until 22 September

This exhibition offers a comprehensive look at Sonya Clark’s wide-ranging practice, which often employs everyday materials—like flags, cotton cloth, human hair, school desks and brick—to inquire about both the Black American experience and broader questions about community and our often-underappreciated interdependence on one another. For works like her ongoing performance Unraveling (2015-present), a thick Confederate flag hangs in the gallery and is slowly pulled apart, thread by thread, often with viewer participation. In The Hair Craft Project (2014), Clark shines a spotlight on hairdressers, articulating their craft as one worth celebrating and elevating to the realm of high art. Beyond an indictment of our shameful past, Clark’s work celebrates the miraculous potential of the present and the future. W.L.

Toshiko Takaezu, Closed Form, 2004. Private Collection. Photo: Nicholas Knight. Courtesy The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum. © Family of Toshiko Takaezu

Toshiko Takaezu: Worlds Within

Noguchi Museum, until 28 July

A touring retrospective centred on the life and work of the late artist Toshiko Takaezu (1922-2011), Worlds Withinfeatures around 200 works that track the formal and conceptual progression of her practice over her six-decade career as a ceramicist, weaver and painter. In her work, Takaezu was “reaching for something transcendent and profound”, says the Noguchi Museum curator, Kate Wiener, who co-organised the show with art historian Glenn Adamson, composer and sound artist Leilehua Lanzilotti, and former Noguchi Museum senior curator Dakin Hart.

Takaezu focused on so-called “closed form” ceramic sculptures, a term that is both descriptive but also a “consciously charged phrase”, according to Adamson. “The use of the term ‘form’ suggests an alignment to modernism and the domain of abstraction,” he says. “The closure results in a withholding of the interior of the object, making it a space only accessible to the imagination, and also an exterior which is totally continuous, which Takaezu then embraced as a painterly field.” G.A.

Walton Ford, Study for “Verfolgen”, 2018. The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the artist, 2019.213. © 2024 Walton Ford. Photography by Janny Chiu.

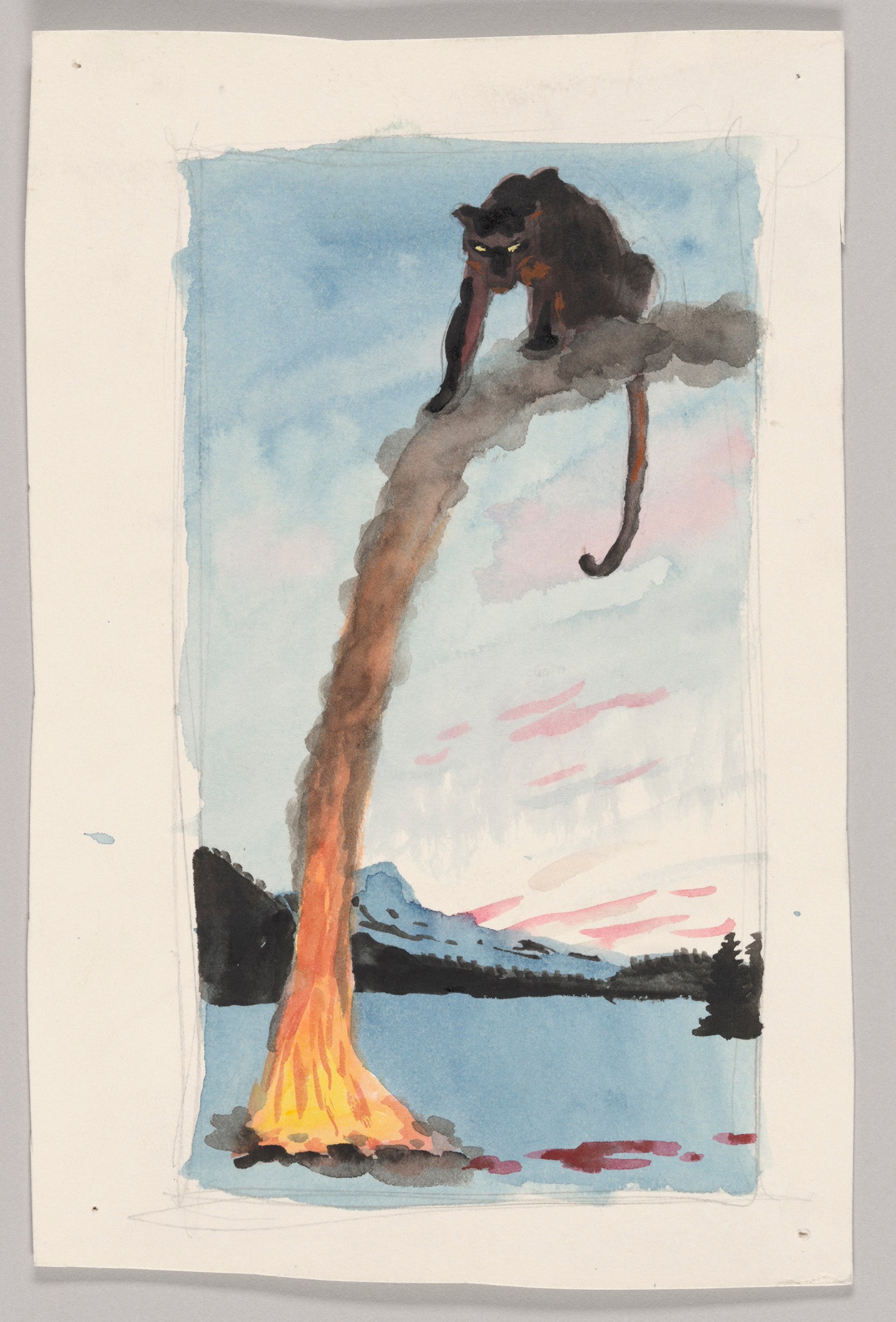

Walton Ford: Birds and Beasts of the Studio

Morgan Library & Museum, until 6 October

The American artist Walton Ford is known for approaching the Old Master genre of animal painting with a contemporary twist, creating monumental watercolours of wildlife that are imbued with historical and literary references and humour. His exhibition celebrates his gift of 63 sketches and studies to the Morgan, which are displayed alongside some of their respective paintings and a selection of works from the institution’s permanent collection. “I’ve been making large-scale watercolours for decades and each had studies that went into their making,” Ford says. “These were working drawings and watercolours that wound up on the studio floor covered in footprints or were thrown into boxes. I didn’t think there was value in them except informational value. Working with [art historian] Isabelle Dervaux, I became more comfortable with the idea that these things littering the studio floor were worth sharing and that people might be interested in knowing how I work.” G.A.

Weaving Abstraction in Ancient and Modern Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art, until 16 June

This incredibly rich textile exhibition spans millennia, bringing exquisite ancient Andean artefacts—including vibrant pieces made with thousands of macaw feathers—into dialogue with Modern and contemporary works by four masters of woven art: Anni Albers, Sheila Hicks, Lenore Tawney and Olga de Amaral. The historic objects are improbably well preserved and modern, like the colourful figures flying across a textile fragment from Peru’s Paracas Peninsula that has been dated tobetween the 5th and 2nd century BC, or a 16th-century tunic with a chequered pattern and bright pink collar, which looks like it could have been on a runway during the most recent Paris Fashion Week. In the textile art pieces from the 20th century, Albers, Hicks, Tawner and De Amaral test the limits of the form, introducing new techniques, processes and materials to dazzling effect. B.S.

Installation view of Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better than the Real Thing featuring Rose B. Simpson, Daughters: Reverence, 2024 Photograph by

Audrey Wang

Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing

Whitney Museum of American Art, until 11 August

The often-subtle resonances between pairs or groups of works in the 2024 Whitney Biennial—curated by Chrissie Iles, a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Meg Onli, a Whitney curator-at-large based in Los Angeles—are a departure from the loud themes of recent editions. It is, as Iles writes in her catalogue essay, “an exhibition made as a set of relations”. To be sure, there are dramatic gestures, too, like a teetering replica of the White House made from dirt by Kiyan Williams, which will be reshaped by the elements over the course of the show.

The exhibiting artists’ engagements with the titular “real” are generally less concerned with current events and more about questions of authenticity and identity. “These artists want to destabilise the ways that identity gets flattened within the art world,” Onli says in an interview in the exhibition catalogue. “In organising this biennial, Chrissie and I have had to consider a political moment as feverish as the culture wars of the 1990s. Artists are still struggling to make sure they are not essentialised.” B.S.