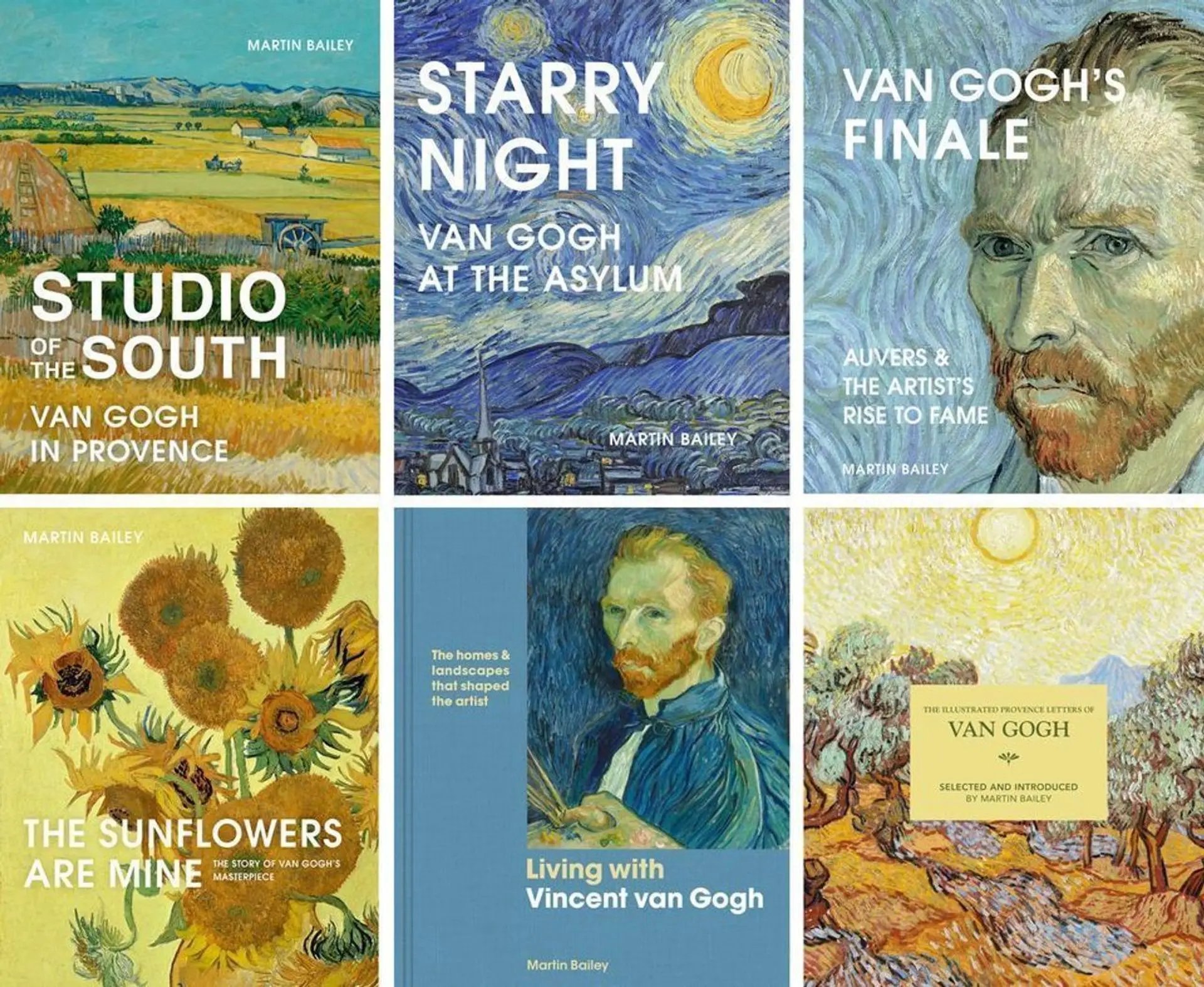

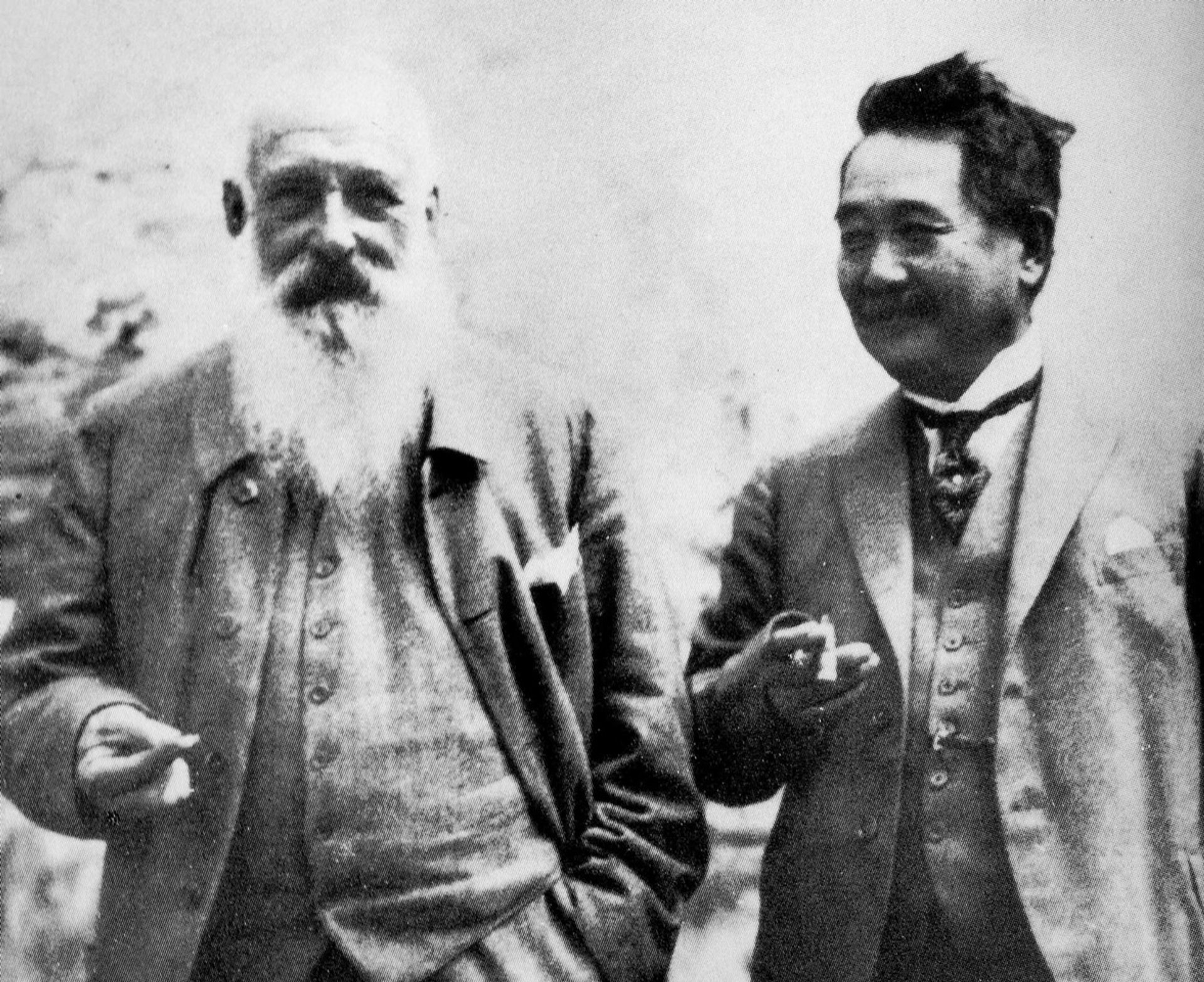

Although now little known outside Japan, Kojiro Matsukata (1865-1950) was one of world’s great collectors in the early 20th century. He set out to establish the first museum of European paintings in Tokyo, to be known as the Sheer Pleasure Art Pavilion. Among his collection were apparently 25 works by Claude Monet—plus three Van Goghs.

Kojiro Matsukata smoking with Claude Monet on a visit to Giverny (1921)

Kawasaki Heavy Industries Ltd, Tokyo

The Matsuka collection was initially amassed under the guidance of the British artist Frank Brangwyn, who also designed the planned building. In an astonishing ten-year spending spree from 1916, the wealthy Japanese dockyard owner bought around 2,000 artworks, mostly in France. But during the 1920s Matsukata faced serious financial problems and the museum idea had to be abandoned.

Kojiro Matsukata (early 1900s) Kawasaki Heavy Industries Ltd, Tokyo

His collection included a Van Gogh “flowerpiece in a vase”, which is likely to have been a still life painted in Paris in 1886-87. This picture is recorded in a pre-war inventory discovered a few years ago in London’s Tate Archive. It lists 316 Matsukata artworks which had been stored at the Pantechnicon warehouse in Westminster.

The Van Gogh was valued at £1,000, which made it among the most valuable works, along with paintings by Edouard Manet and James Whistler. But most of Matsukata’s works stored in London were by British artists, so this makes it quite possible that the Van Gogh had been originally bought from a London dealer. However, no photographs survive of the painting and without a more detailed description it is impossible to identify the flower still life.

The Pantechnicon today Photo: The Art Newspaper

The Pantechnicon was a furniture depot on London’s Motcomb Street, which had been built in 1834 (it later gave its name to the word “pantechnicon”, a large removal vehicle). On 9 October 1939 there was a serious fire in the building. Although this was just a month after the outbreak of the Second World War, it was an accident and not caused by enemy action.

A memorandum by the Arthur Tooth gallery in the Tate archive records that “the whole of the Matsukata Collection was burnt in the Pantechnicon fire, with the exception of about 3 pictures”. The Van Gogh was almost certainly destroyed, although there remains a very remote possibility that it might have been saved and then went missing.

After the war the Pantechnicon was rebuilt behind the original Greek-style facade and it continued to serve as a warehouse until the 1970s. By a curious coincidence, part of the building is now occupied by a Japanese café, Kitsuné.

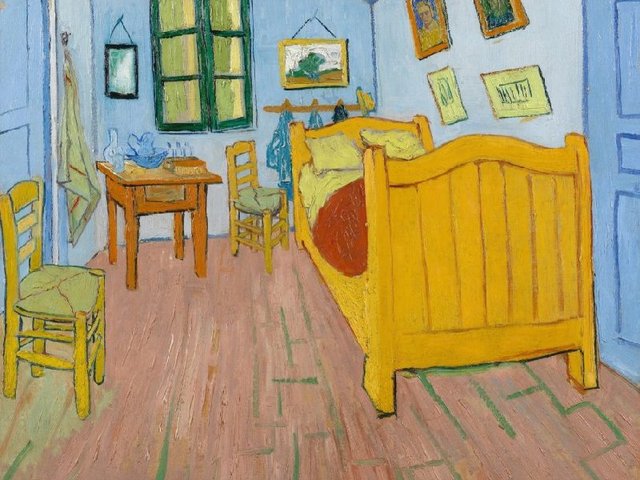

Van Gogh’s The Bedroom (September 1889) Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Even if Matsukata lost his flower still life, he still had two Van Goghs, most notably one of the three versions of Van Gogh’s Bedroom (September 1889). This had been bought in 1922 from the Paris dealer Paul Rosenberg for 110,000 francs (around £900). It remained stored in France and was not shipped to Japan.

In 1944, after the liberation of France during the Second World War, The Bedroom was sequestered by the French government, on the grounds that Japanese resident Matsukata was an “enemy alien”.

After the war, the Japanese prime minister in July 1951 formally asked the French government to give up The Bedroom and three other key works by Edouard Manet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Auguste Rodin. This was refused. Then in 1958 an agreement was made between Japan and France under which 20 of the finest Matsukata paintings, including the Van Gogh, would remain in France. This explains why The Bedroom now belongs to the Musée D’Orsay.

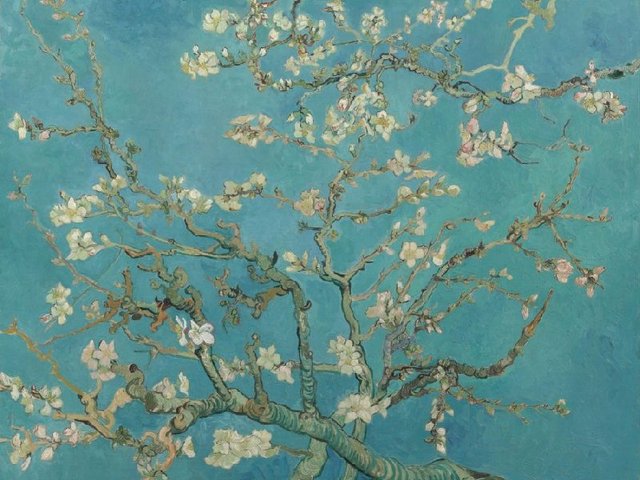

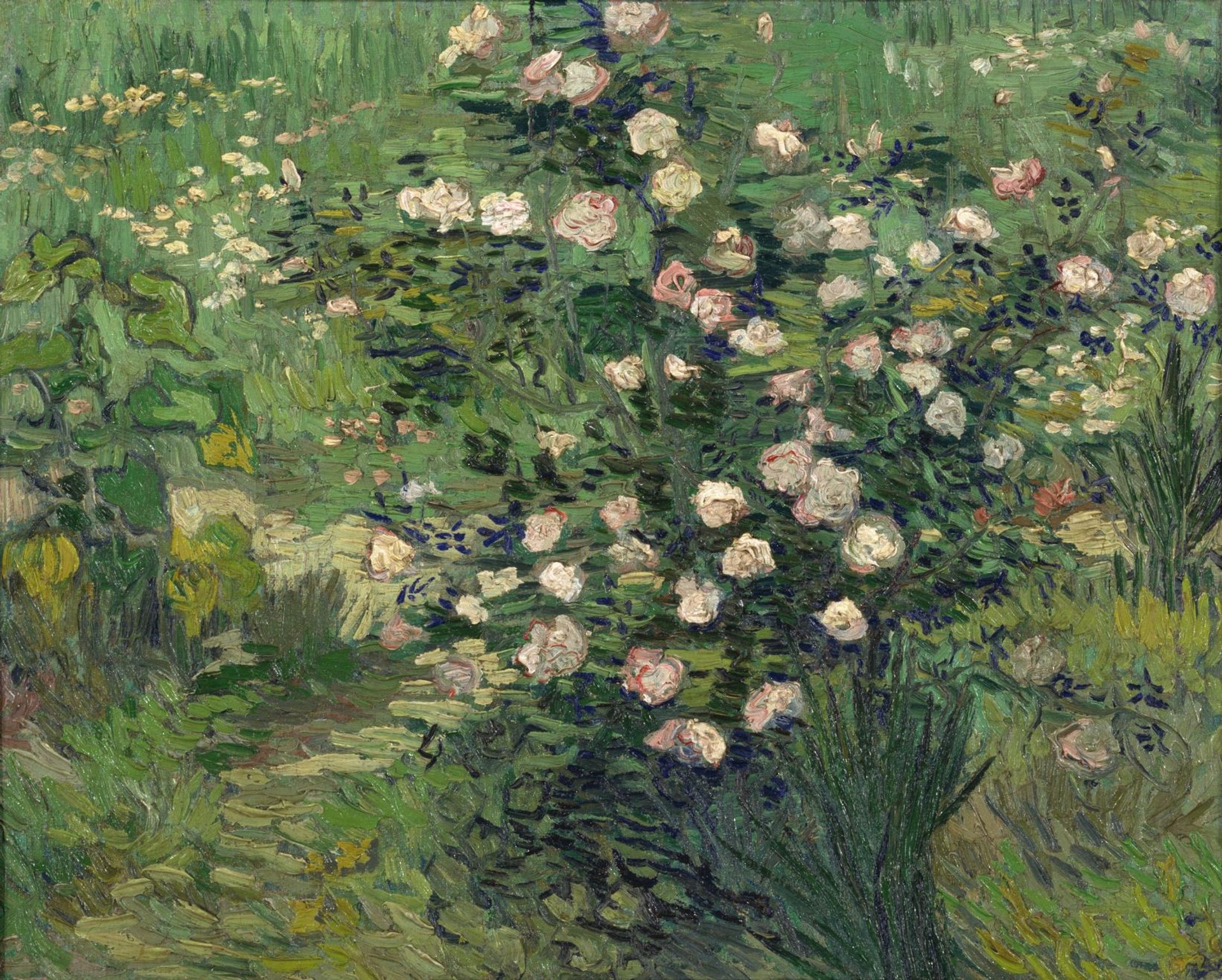

Van Gogh’s Roses (May 1889) National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo

The bulk of the Matsukata pictures were gifted to Japan on condition that they would be displayed in a new museum of European art, designed by the architect Le Corbusier. Opened in 1959, it is known at the National Museum of Western Art (363 Matsukata works provided the core of collection, but it has since been greatly expanded with just over 5,000 acquisitions).

Among the works sent back to Japan was Van Gogh’s Roses (May 1889), which Matsukata had also bought from Rosenberg in 1922. He had then paid 3,000 francs (around £25). The picture depicts flowers which Van Gogh painted a few days after his arrival at the asylum just outside Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. With the Japanese love of gardens, Roses and the lost flower still life must have held a particular appeal for Matsukata.