A new book by the Dutch museum curator Alexandra van Dongen sheds fresh light on intriguing features in Van Gogh’s most iconic paintings. Her discoveries will also be presented in an exhibition at the Van Gogh House in the southern Dutch village of Zundert, the artist’s birthplace.

In Closer to Vincent: Everyday Objects in the Work of Vincent van Gogh, the title of both the book (to be published in Dutch on 30 July) and the exhibition (30 July-30 October), Van Dongen encourages us to examine minor details in Van Gogh's paintings. Although we don’t normally pay attention to these items, she believes that they “help us to better understand Van Gogh’s pictures, once we reflect on the actual objects that he used”.

Van Dongen, a curator of historical design at Rotterdam’s Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, is well placed to guide us through the objects and the art. She concludes that “Vincent always observed the material objects that he depicted in his work with great attention to their characteristics, usually depicting them in a realistic way”. I will present five examples.

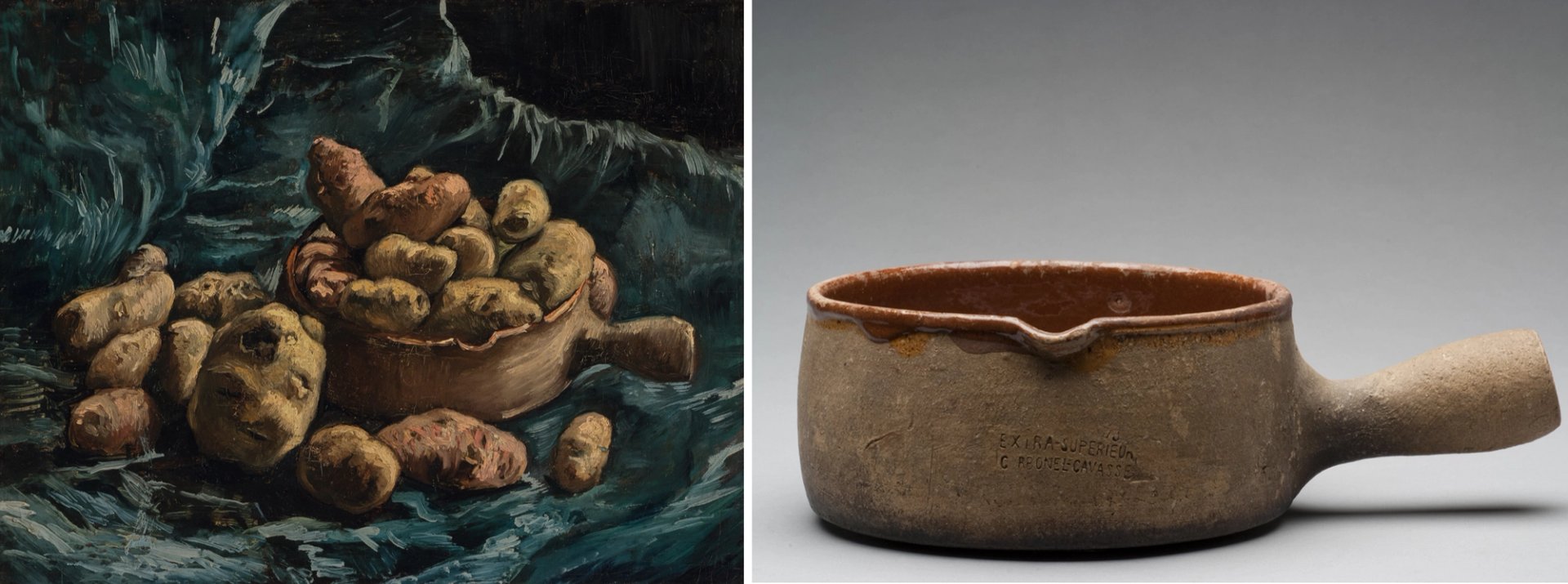

Still-life with Potatoes

Van Gogh’s Still-life with Potatoes (1886-87) and casserole “Parisienne” (Vallauris, late 19th century) Credit: Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, Rotterdam and private collection (shared ownership of painting) and Guy Mombel, France (private collection)

Identifying the earthenware casserole helped redate this painting. Still-life with Potatoes had been thought to have been painted in around September 1885 in Nuenen, the village in the south of the Netherlands where Vincent’s parents then lived. But Van Dongen identified the casserole as French, a popular design known as “Parisienne” and made in Vallauris, in south-east France.

This made her think that the still life would have been more likely to have been done after Van Gogh’s arrival in Paris in February 1886. This redating was confirmed when new technical research revealed that the canvas had been sold by the Paris-based Tasset et L’Hôte company. It is likely that the casserole would have been in the kitchen of the apartment that Theo shared with his brother Vincent, since Vallauris pans were in use in many French kitchens.

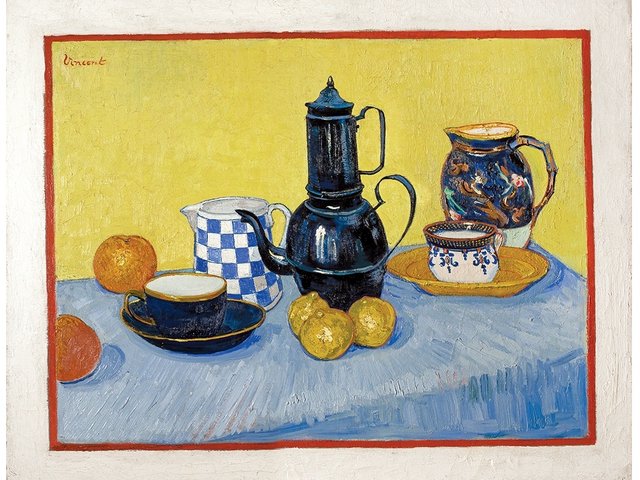

Still-life with Coffee Pot

Van Gogh’s Still-life with Coffee Pot (May 1888) and jug (Sarreguemines, late 19th century) Credit: Goulandris Collection, Athens and Jos van der Kleij-Penders (private collection)

Still-life with Coffee Pot was painted a fortnight after Van Gogh rented the Yellow House in Arles in May 1888. Excited at being able to move into the first house he had ever rented for himself, Vincent wrote to Theo, saying that he had “bought what I need to make a little coffee or broth at home, and two chairs and a table”.

The purchases included what he described as “a pale blue and white chequered milk jug”. Van Dongen has identified the distinctive jug as French industrial earthenware, of a late 19th-century design, from the Sarreguemines factory, near the German border.

Van Gogh loved complementary colours, such as blue and orange, describing his painting as “a variation of blues enlivened by a series of yellows ranging all the way to orange”. This would help explain his choice of this striking jug. He added a contrasting painted orange border to the picture and outside this a wide white border on the canvas.

Still Life

Van Gogh’s Still Life (May 1888) and jug (Phoenix, Stoke-on-Trent, probably 1880s) Credit: Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia and private collection

The same dark blue jug which is on the right side of Still Life with Coffee Pot reappears centre-stage in the Still Life with flowers, which was done in the same week. The pot has been identified by the ceramics specialist Dimitrios Bastas as British majolica ware, with this particular example being made by the Phoenix works of Thomas Forester in Stoke-on-Trent. Such pieces were exported to France, so it was presumably bought by Van Gogh in Arles (or taken by him from Paris).

Van Gogh was aware of the jug’s origins since he described it as a “majolica jug with red, green, brown designs”. Once again he played with complementary colours—the blue jug and another orange painted frame.

The earthenware jug has relief moulded decoration of cranes, cherry blossoms and bamboo. These motifs would have struck a chord with Van Gogh, a great admirer of the art of Japan. But he correctly realised that it was European majolica, not mistaking it for a real Japanese object.

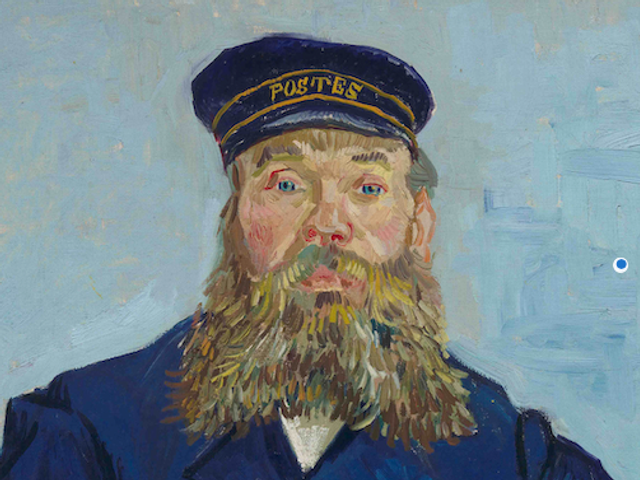

Portrait of Joseph Roulin and La Mousmé

Van Gogh’s La Mousmé (August 1888) and original willow chair (probably Provence, late 19th century) Credit: National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC and Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Van Gogh’s Portrait of Joseph Roulin (August 1888) and drawing of Portrait of Joseph Roulin (August 1888) Credit: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (gift of Robert Treat Pain 2nd) and private collection

In August 1888 Van Gogh used the same willow chair in two of his portraits, that of his postman friend Joseph Roulin and a 12-year-old girl whom he called “La Mousmé”, a Japanese term for a young girl. Van Gogh described the chair as “cane”.

With Roulin, Van Gogh complained that “he was getting too stiff while posing, and that’s why I painted him twice, the second time at a single sitting”. The first picture shows the postman sitting on the willow chair whereas the second was just a bust portrait. This suggests that the tendril-shaped chair may not have been as comfortable as it looks (or perhaps Van Gogh insisted that the postman remain on it motionless for too long).

When Van Gogh left Arles for the asylum, he stored his furniture with his neighbours, Marie and Joseph Ginoux. A year later, just after he had left the asylum, he wrote to say that he only wanted the bed, mattress and mirror returning, and they could keep the rest of the furniture, including “chairs”.

The willow chair later passed to Marie’s niece, Marie Jonquet, and in 1960 it was acquired by the Belgian Van Gogh specialist Marc Tralbaut. Nine years later it was given for the planned Van Gogh Museum, but due to its weak condition it has been kept in storage.

Although the curves of the chair in Van Gogh’s pictures may appear to be exaggerated, seeing a photograph of the actual chair suggests that the artist has fairly accurately depicted its form.

Marie’s chair was deemed too fragile to be lent for the Zundert exhibition. The Van Gogh House has therefore commissioned a willow replica made by the Zundert furniture maker Rien Stuijts to be displayed in the exhibition.

Sunflowers

Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (August 1888) and pot (southern France, late 19th century) Credit: National Gallery, London and Martin Bailey, London

Van Gogh's legendary Sunflowers (August 1888, version at London’s National Gallery) were depicted in what the artist described as “a yellow earthenware pot”. Although once very common, pots of the style used by Van Gogh (without handles) are now fairly scarce. I bought one a few years ago and it has been requested for the Zundert exhibition.

These rustic terracotta vessels were made in the south of France for storing food and are known as pots à confit (preserving pots). The wheel-turned earthenware was glazed inside to seal it and also on the top half of the exterior, using a lead glaze which leaves a shiny yellow-ochre colouring.

Nineteenth-century artists often chose elegant vases for floral still lifes, but it is typical of Van Gogh that he opted for a more humble vessel.

On first picking up my pot in the shop where I bought it, it was immediately obvious that a bouquet of sunflowers could never have stood upright in it. Even filled to the brim with water, the pot would hardly have been heavy enough to support more than a few blooms, let alone the fifteen in Sunflowers. The vessel’s fairly wide mouth also meant that tall flowers would never have stood upright.

Van Gogh was not painstakingly copying a pot of sunflowers beside his easel. Instead he probably put the two elements together in his mind, possibly aided by having an empty pot and a separate bouquet in a more practical vessel near his easel.

Closely examining the pot made me realise quite how much there is to be gained by contemplating the objects depicted in Van Gogh’s paintings. Van Dongen in her forthcoming book and the Zundert exhibition has done precisely that.

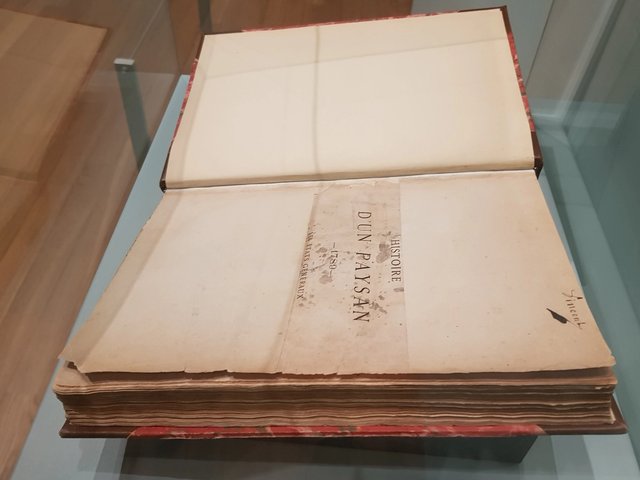

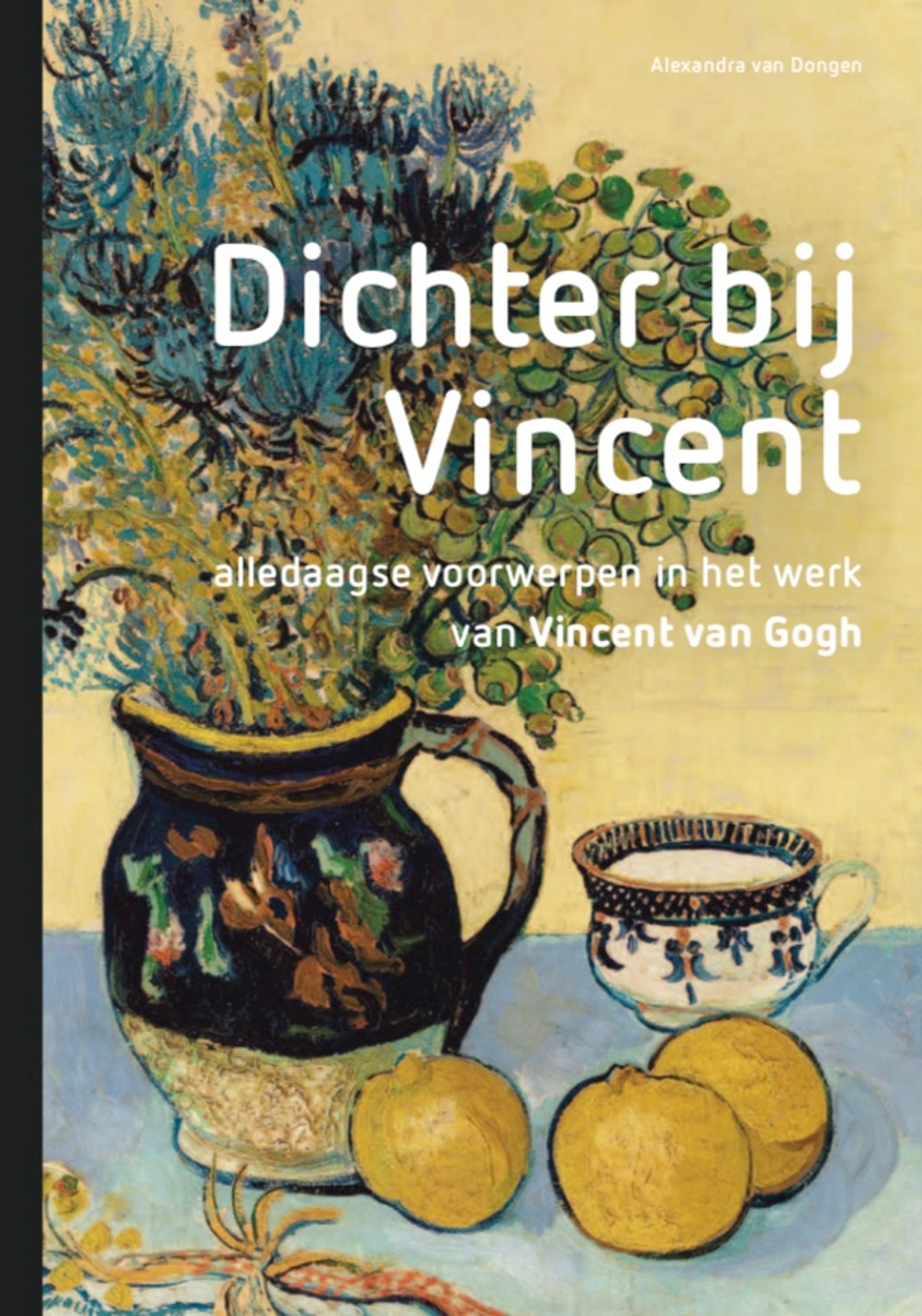

Cover of Alexandra van Dongen's book Closer to Vincent: Everyday Objects in the Work of Vincent van Gogh, to be published in Dutch by Sterck & De Vreese on 30 July