“It is the great fault of capitalism, which has rotted and still rots everything,” the Jewish-French art dealer Léonce Rosenberg (1879-1947) wrote in 1937. Quoted towards the end of Léonce Rosenberg’s Cubism: The Galerie L’Effort Moderne in Interwar Paris, an energetic and erudite study—the first on the dealer—the lament is an about-face to his 1921 rallying cry of “long live the sale!”

These opposite positions denote both intrinsic contradictions within Rosenberg and extrinsic events (Fascism, the Wall Street Crash of 1929), which saw his position change from that of an influential art visionary to a member of an oppressed minority in Nazi-occupied Paris, stripped of his business and art collection.

Taking a thematic approach, ranging from an examination of Platonism in Cubism to Cubism and nationality, Giovanni Casini’s book is argument-driven and intelligent. Notably, the author (via Rosenberg) successfully positions Cubism as a heterogenous and international movement irreducible to Paris and the analytic-synthetic spectrum. By example, in his gallery L’Effort Moderne, and its influential journal, Rosenberg promoted Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Juan Gris, alongside artists from Mexico (Diego Rivera), Brazil (Vicente do Rego Monteiro) and Australia (John Wardell Power) and styles ranging from de Stijl (Piet Mondrian), Surrealism (Giorgio de Chirico) and Purism (Fernand Léger).

He argued that Cubism was the synthesis (indeed apotheosis) of intellectual and visual cultures uniting the “East” and “West”

Across these styles, Rosenberg responded to purity, emotion and mystery, soliciting Plato, theosophy and his Jewish heritage to argue (sometimes in a strained fashion) that Cubism was the synthesis (indeed apotheosis) of intellectual and visual cultures uniting the “East” and “West”.

Rosenberg’s aesthetic hybridity correlates with his identity. In his era, Cubism was denigrated as Boche (German) because it was successfully represented by Rosenberg and other Jewish art dealers (Joseph Hessel, Wilhelm Uhde, Alexandre Bernheim-Jeune, Nathan Wildenstein etc). According to Casini, Rosenberg tried to redeem it by inscribing Cubism within the French rhetoric of “tradition”. Concurrently, the dealer adopted artistic and ethnographic theories to fuse identity markers otherwise regarded as incompatible in war-ravaged Europe.

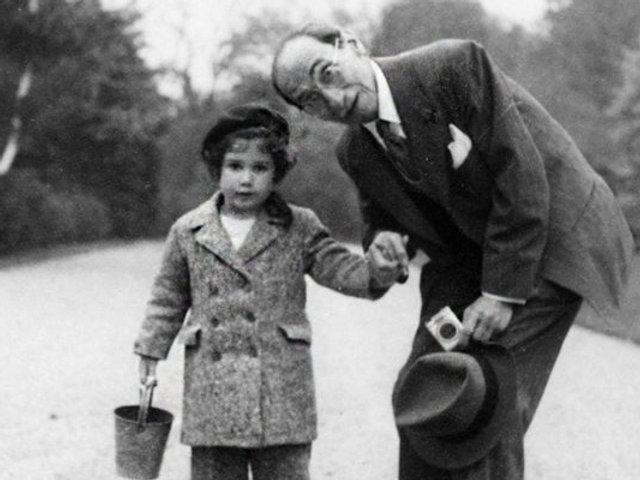

Rosenberg presented himself as Jewish, French, international and cosmopolitan, but ultimately Fascism, nationalism and the art market refused to embrace this intersectionality. This close relationship between aesthetics and identity was symbolised in Rosenberg’s Gesamtkunstwerk apartment at Rue de Longchamp in Paris (1927-32) some contents of which are now reunited in the ongoing exhibition Léonce Rosenberg’s Apartment: De Chirico, Ernst, Léger, Picabia… (curated by Casini and Juliette Pozzo) at the Musée Picasso in Paris until 19 May. Designed by Rosenberg, the apartment was a crucible for his ideas and aesthetics, and a home where he could enact his identity freely.

Like his predecessors and peers, Rosenberg utilised a number of strategies common in the modern market. He established exclusive contracts with artists, created a monopoly for individual artists, published an in-house journal, curated monographic exhibitions and worked closely with international collectors including Helene Kröller-Müller.

His more successful brother, Paul, “swiped” Picasso from L’Effort Moderne

Business, however, went up and down. He frequently sold his collection to generate funds for his enterprise (in New York City in 1918 and Amsterdam in 1920) and lost his artists to competitors. In 1918, his more successful brother, Paul, “swiped” Picasso from L’Effort Moderne. And in 1921 Rosenberg became persona non grata when he acted as a specialist for the Hôtel Drouot auctions of the collections of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and Wilhelm Uhde, which had been confiscated by the French government during the First World War because, as German citizens, both men were considered enemy aliens.

The auction’s acid test

This episode reveals contradictions in Rosenberg’s character. Rosenberg believed himself to be an éditeur d’art rather than a marchand, but when artists, including Braque, Léger, André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, argued that the Drouot auction would financially devalue their work, Rosenberg’s public response was brutal. “Either these artists have value or they have not,” he declared. “If they have none, then long live the sale! Which will definitely expose unworthy artists.”

Taking Rosenberg’s lead, Casini argues that the auction remained important for promoting the Cubism brand and attracting new audiences. This lets Rosenberg off lightly, given his gallery was the key beneficiary of the sale (second only to the syndicate of buyers organised by Kahnweiler to regain his collection).

“You took my money for years and in return left me with unsaleable ‘crusts’”

“You took my money for years and in return left me with unsaleable ‘crusts’,” Rosenberg wrote to the painter Gino Severini in 1922. Attacks such as these, alongside the Hôtel Drouot auction, damaged Rosenberg’s standing within (and possibly contributed to his erasure by) the art world. His theories and achievements were also subsequently obfuscated when Cubism’s narrative was rewritten by curators such as Alfred Barr at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in the 1930s.

Although drawing heavily on dealer archives, this volume is atypical in art market studies. Casini eschews chronology, an exhibition history list (which would be welcome), and inventory or sales analyses. Instead he uses Rosenberg as a prism, through which themes collect, refract and disperse. Despite Rosenberg’s contradictory actions in his lifetime, he emerges in this account as a bona fide champion of Modernism and a man more sinned against than sinning.

• Léonce Rosenberg’s Cubism: The Galerie L’Effort Moderne in Interwar Paris, by Giovanni Casini. Penn State University Press, 254pp, eight colour and 47 b/w illustrations, $119.95 (hb), published 28 December 2023