When the artist and curator Stephen Nowlin landed up in Los Angeles in the late 1960s, he was an art school dropout in search of an environment attuned to the possibilities of the age. “Nasa astronauts were about to set foot on the Moon,” he wrote in a 2017 essay. “I had felt the tidal surge of young instinct that convinces youth a new path is unassailable.” He went on to make art that was deeply engaged with astronomy, and got a job at Caltech’s Astro-Electronics Lab after hearing about the school’s artist-in-residence programme.

Noteworthy overlaps between artists and scientists in Los Angeles had, in fact, begun decades before, as is clear from two PST Art exhibitions—Crossing Over: Caltech and Visual Culture, 1920-2020 (Caltech, 14 September-7 December) and Particles and Waves: Southern California Abstraction and Science, 1945-1990 (Palm Springs Art Museum, 14 September-24 February 2025). In the 1960s, these overlaps were increasingly formalised, with initiatives such as the Caltech artist-in-residence project and Nasa’s art programme, which commissioned artists to interpret the possibilities of space travel.

In 1970, Nasa tapped Edward C. Wortz, a Los Angeles scientist who studied weightlessness and temperature control for astronauts, to lead its inaugural National Symposium on Habitability (specifically, the habitability of space). Wortz roped in Robert Irwin and other Los Angeles artists to help him plan the symposium, underscoring a synergy between the science of space and the Light and Space art movement coming out of Southern California.

Experimental equals

However, examples like this, while plentiful enough, might suggest more fluidity between the fields than actually existed. Helen Pashgian, the only female artist to participate in the first Caltech artist-in-residence programme, puts it bluntly: “It wasn’t a very successful programme.” She found some scientists too focused on the theoretical implications of their work to help her figure out how to make things. But, she adds: “It was all about experimentation.” The parallels between artists and scientists engaged with outer space—rocket scientists, astronomers, astrophysicists—reflect that spirit of experimentation particularly well. Artists could fill in the hard-to-fathom nature of the cosmos with their imaginations and their material explorations.

Crossing Over was curated by Peter Collopy, a historian of science who directs the Caltech Archives, and Claudia Bohn-Spector, an art historian. They were surprised by how much visually enthralling material they found in Caltech’s archives after combing them with the help of ten other scholars. Bohn-Spector says: “At first you think, oh my God, science is a lot of dry stuff and a lot of manuscripts and graphs.” She ended up finding more “fantastic to look at” material than could be included and had a hard time whittling the list down to 300 objects.

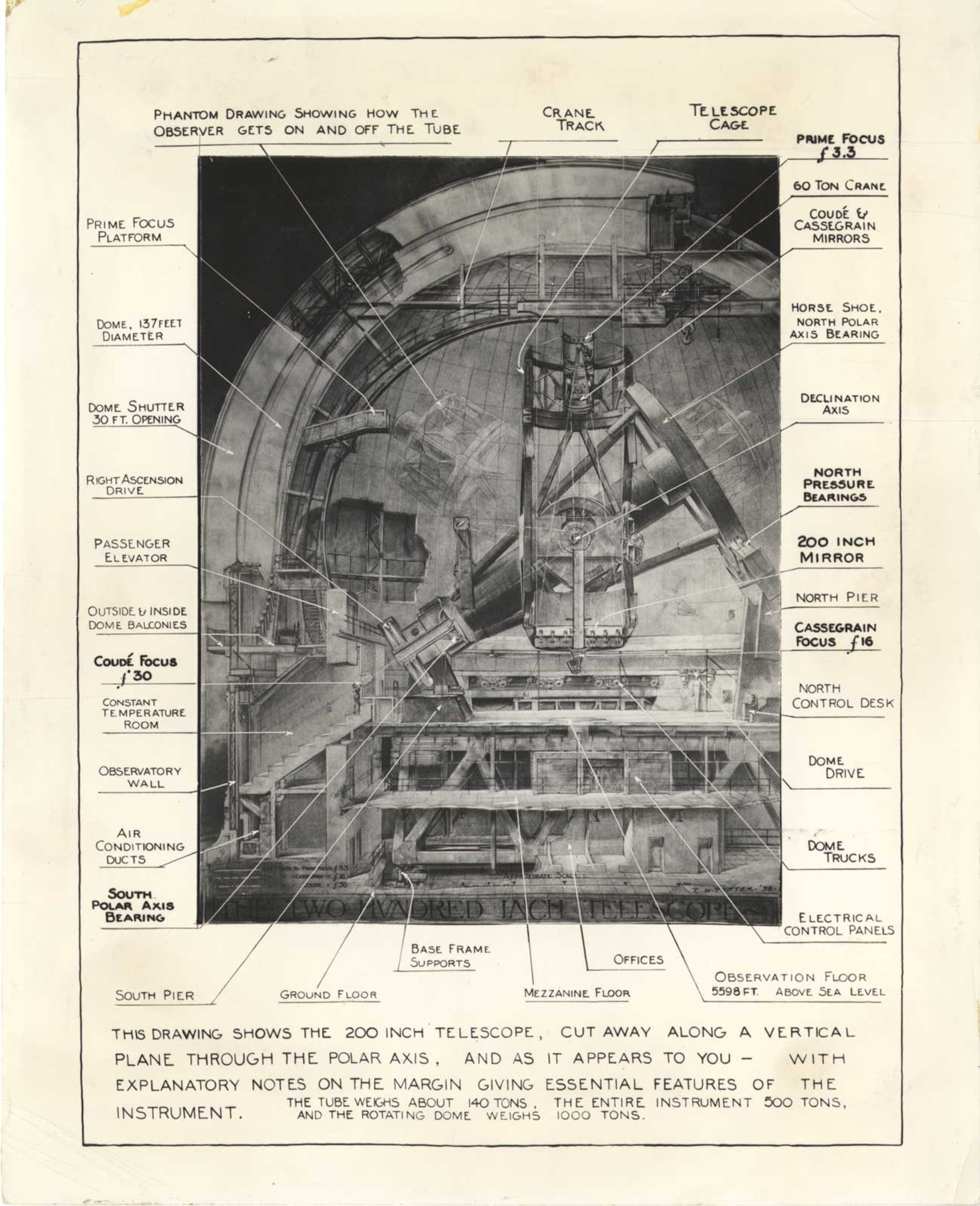

Crossing Over incorporates work that artists made and showed at Caltech, alongside images made by scientists and artist-made renderings of scientific discoveries and speculative illustrations. It spans five Caltech campus sites and begins in the Robinson Laboratory of Astrophysics, which was built with a dome for a telescope pointed at the sun. The exhibition starts with an image of the sun, projected from that telescope on to frosted glass, and proceeds to trace, through images and objects, the history of the Palomar Observatory. Designed in the 1920s by George Ellery Hale, the observatory was famous even before its 1948 completion. The exhibition includes intricate 1930s pencil and ink drawings by Russell Porter, an architect and amateur telescope builder, including a cutaway drawing of the not-yet-built 200in telescope.

“He used this incredible imagination to visualise these things before they actually happened,” Bohn-Spector says. The artist Alfred Crimi took a much flashier approach in a 1945 painting he made for a cover of Popular Science magazine, in which the towering orange-red telescope makes the men working at its base look like miniature mad scientists straight out of a sci-fi film. Works by Porter and Crimi share space with photographs of users of the telescope as well as images made with it. “The boundaries between what is art, what could be art and what is not art are rather fluid,” Bohn-Spector says.

The exhibition also mines the deep entanglement between science fiction and rocket science. As Collopy points out, many of the founders of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory were “obsessive science fiction readers”, in part because there was so much scepticism about space exploration. “Serious scientists didn’t think it was going to happen,” Collopy says. “It was only people who were thinking about it fictionally who thought that it might be real. Science fiction plays a really huge role in the depiction of the rocket.”

Future vision: Russell Porter’s 1930s drawing of the Palomar Observatory’s 200in telescope features in Crossing Over

From here to infinity

Artists also saw potential in the gap between the real and the possible. “For a lot of artists, the new ways of seeing, especially in technological advancements in astronomy, captured their attention,” says Sharrissa Iqbal, an art historian and curator who is organising Particles and Waves with co-curator Michael Duncan. “It allowed them to work in abstract modes because this kind of research was itself abstract.” For instance, Frank Malina, the aero-nautical engineer and painter, brought a scientific rigour to his kinetic paintings—such as Mitosis (1974), included in the show—but the resulting images were visual experiments, not representations of scientific realities.

Some works in the show, such as Channa Horwitz’s, take loose or intuitive inspiration from science, but others emerge from in-depth engagement. Malina remained a practising rocket scientist even as he experimented with painting techniques, while Fred Eversley worked as an aerospace engineer before becoming an artist who incorporated his scientific knowledge into sleek spheres and orbs.

The printmaker June Wayne, who established a friendship with Richard Feynman, the theoretical physicist, feared that an attempt to colonise space would devour our planet’s resources. Her Space Exploration works pulsed with repetition and celebrated the unknowability of the cosmic. For Claire Falkenstein, a prolific Los Angeles sculptor, space exploration had profound implications for the actual and conceptual shapes that works of art could, and should, take. Her Never Ending Screen (1975) series, one of which will appear in Particles and Waves, consists of branch-like, polished aluminium forms repeated into an expanding matrix. As she explained in 1976, she felt a need to express “an idea of extension into outer space, of no ending, of infinity”.

PST Art: Art & Science Collide opens in September 2024. Read all our preview coverage here