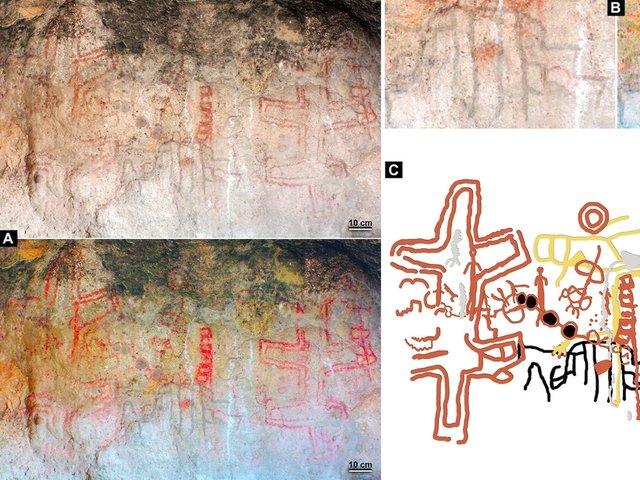

A groundbreaking study of ancient cave paintings in Puerto Rico has pushed back the record of precolonial cultures on the archipelago. Some of the oldest pictographs sampled date to between 740BC and 400BC—centuries before Spanish colonisers contended that the Native population first settled there.

The archaeologist Reniel Rodríguez Ramos and the geophysicist Angel A. Acosta-Colon studied 11 karstic caves on La Isla Grande, Puerto Rico’s main island. They collected pigments from 61 pictographs, hoping to form a clearer timeline of humans in the area. “Although there have been extensive efforts to record the rock art that has been discovered in Puerto Rico and the Caribbean, until now there was no good information on their chronology,” Rodríguez Ramos tells The Art Newspaper. “The chronology was based on formal typologies—or how these images visually changed through time. But there was not enough information to determine when particular traditions began.”

It was previously thought that rock art in Puerto Rico, which includes pictographs, petroglyphs and pyroglyphs, started after 600AD. Spanish colonisers held that the Taíno population—largely decimated following the Spanish conquest in 1493—had arrived on the island just 500 to 1,000 years earlier, according to Rodríguez Ramos.

“For a long time, researchers believed that the Taíno were the only living culture here prior to the invasion of the Spaniards,” Rodríguez Ramos says. “Through extensive archaeological research, we have determined that people were living in Puerto Rico for thousands of years prior to the Spaniards’ arrival.” He adds that the new findings “rewrite the idea that the Spaniards killed off all the Indigenous people on the island”, reinforcing the anthropological argument that the Taíno were not extinct but rather merged with African and Hispanic cultures, as evidenced in cave drawings made well after colonisation. The research further “allows for a greater understanding of how our earliest ancestors viewed the world and what was important to them”, Rodríguez Ramos says.

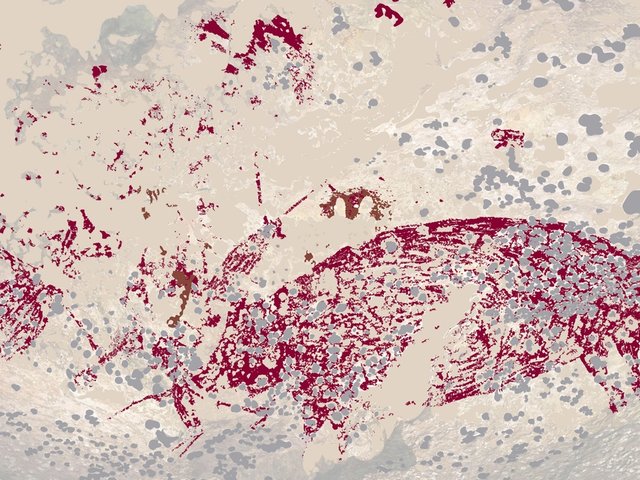

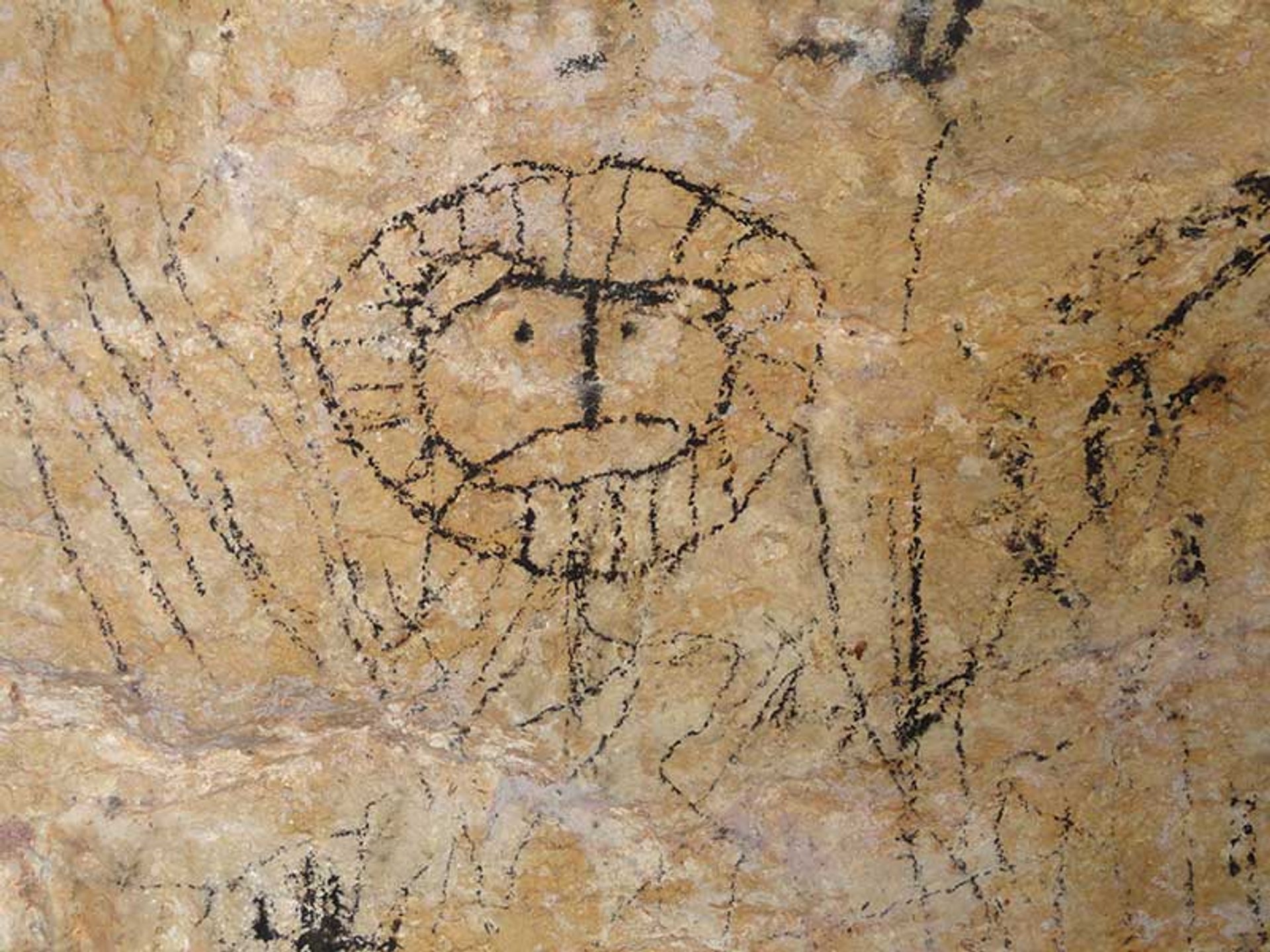

The study also found that rock art did not cease after Puerto Rico was first colonised. Some of the most recent pictographs sampled date to the 18th century. One particularly striking example is a 16th-century image that resembles a lion, which prompted some experts to speculate that the painting could have been made by an enslaved African brought to Puerto Rico who would have seen a lion first-hand. However, Rodríguez Ramos explains that the so-called lion “could also have been a solar representation”, as similar examples exist at other sites in the Caribbean. “The idea that African people were creating their own rock art is something that must be studied, since there are examples in the Virgin Islands, Cuba and Hispaniola,” Rodríguez Ramos adds.

A pictograph resembling a lion has led to speculation that it may have been created by an enslaved African

Courtesy Reniel Rodríguez Ramos/University of Puerto Rico at Utuado

Some pictorial elements include animals more familiar in Puerto Rico—stingrays, turtles and lizards—while others have anthropomorphic and supernatural elements. The animals could represent what people were seeing around them, or they could have been totemic elements to depict themselves, according to Rodríguez Ramos. “Our research was not aimed at interpreting the meaning of those images, but at least we have a sense of what was happening then,” he says. “Now that we know more about the temporal context, we can delve into what they wanted to portray in terms of meaning and composition.”

Further exploration

Pictographs are made with organic pigments and can be more accurately dated than other forms of rock art, and their study requires samples small enough to preserve the configuration of the paintings. Radiocarbon dating on the La Isla Grande pictographs was conducted using a technique called Accelerator Mass Spectroscopy (AMS). AMS has been used to date pictographs throughout the world since the 1980s, including at well-known sites like the Chauvet Cave in Ardèche, France. It was first used in Puerto Rico in 2016 on pictographs on Isla de Mona, which were found to have been made as far back as the 13th century, spurring curiosity in determining the age of other cave drawings in the region.

“No one was really interested in doing this research in the Caribbean until then,” Rodríguez Ramos says. “It’s a costly process, and we don’t have a laboratory for that in Puerto Rico. But now there’s more interest, and we’re receiving funding from various sources.”

In choosing which pictographs to study on La Isla Grande, Rodríguez Ramos and his colleagues looked at the variability of the rock art and collected a range of samples, from simple to more complex images. In some cases, paintings that were similar and close to one another were examined to determine whether they were done at the same time or if different groups returned to the caves over the centuries.

“We found both cases,” Rodríguez Ramos says. “There were instances where there was regularity, and others where we found images in a palimpsest-like formation, or one on top of the other. We had one panel with an early date of 500BC and, on the same wall, there was a figure dated to the 16th century. People kept coming back to these places.”

The researchers hope that the study brings greater awareness around the preservation of heritage sites and the need for funding for further exploration, particularly in the Caribbean. Puerto Rico has one of the highest densities of rock formations in the Caribbean, and there is still very little known regarding the chronology of more than 500 rock-art sites throughout the archipelago.

“It’s important to underline the significance of rock art as cultural patrimony and a historical resource,” Rodríguez Ramos says. “Throughout the world, people are damaging these images with modern graffiti or touching them with their hands. This is a non-renewable resource. It must be safeguarded for future generations.”