Colleges and universities throughout Florida have been feeling the weight of Governor Ron DeSantis’s “war on woke,” a politically conservative plan to reform the state’s public education system that many see as an assault on academic freedom. From Gainesville to Miami, public institutions devoted to higher education have suffered as a result of increasing attempts to dictate exactly what can be taught there and how, and arts and humanities departments have been especially vulnerable.

The governor’s most recent law, signed in May, establishes content standards in core subject areas that “may not distort significant historical events or teach identity politics and specified concepts related to discrimination”. The bill also prohibits publicly funded institutions from supporting diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) programmes and reduces tenure protections. The language in this new law is very similar to a 2022 bill that a federal judge called “positively dystopian”. Yet even before this latest legislation was passed, there was already right-wing politicking at work at Florida’s public colleges and universities.

Culture control

Sarasota’s New College of Florida is the only public liberal arts college in the state. As a result, New College was one of the first attacked by DeSantis’s education laws. In January, the governor appointed six conservative members to the college’s board of trustees, and that board fired the college’s president and installed a Republican politician in her place. The board then swiftly dissolved the college's diversity office, abolished its gender studies programme, fired a lesbian librarian who was deemed a “troublemaker” and denied tenure to five professors set to receive it. By July, more than a third of the faculty had left, and many students have since transferred to different schools. Some professors and students are now suing the school.

While DeSantis was still setting his eye on New College, there was an effort to “beautify” the campus, which included painting over six student murals. When art students Annie Dong and Hannah Barker returned after their summer break, they discovered that the large-scale, colourful pieces they had worked so hard to create had been destroyed. In making the works, part of an advanced murals class taught in the autumn of 2022 by Kim Anderson, students had done extensive research and written proposals, and their projects had been approved by a committee working on a college-wide initiative to reunite the campus post-Covid.

“The murals elevated and celebrated the students' diversity, cultural heritage, college experiences and LGBTQ+ communities on campus,” Anderson tells The Art Newspaper, adding that all this had taken place “before the overthrow”.

To Dong, now in her senior year, painting over the murals “is another way for them to control the culture”. Her mural had included vibrant Chinese cranes celebrating her identity. Barker, a third-year art student, had covered a wall with Nepali mosaic designs and flora representing the country of her birth. “It feels like we have been erased,” she says.

A spokesperson for New College says that the murals were removed as part of an effort “to resolve the multiple cracks and issues in the stucco” of their buildings, adding: “We will absolutely find a way for our artists to create pieces again, but we must maintain and upgrade all our buildings before greater costs occur.”

It feels like we’ve had our house broken into. At first, we thought it was a bad parodyKim Anderson, art professor at New College of Florida

But Anderson and her students contend that they had planned the locations of the works very carefully and in concert with an expert. “It feels like we’ve had our house broken into,” says Anderson. “At first, we thought it was a bad parody. But, piece by piece, our lives have been more personally affected by the politics here in Florida."

Student backlash

New College is far from the only Florida college flipped upside down by the culture wars. Last year, a Republican senator from Nebraska was appointed president of the University of Florida (UF) in Gainesville, one of the largest universities in the state, which led to backlash from UF’s student body. Around the time that DeSantis’s latest education bill was signed, UF art students and faculty experienced two incidents of harassment.

In March, several banners were suddenly taken down from just outside UF’s off-campus art gallery. They had prison abolition and anti-police messages written on them as part of the show Burn It Down: Communications of Resistance, a collaboration between members of Florida Prisoner Solidarity and UF art students. After the banners were removed at the behest of university administrators (a spokesperson for the college noted that they had been installed outside of the gallery without permission), rocks were thrown through the gallery’s windows.

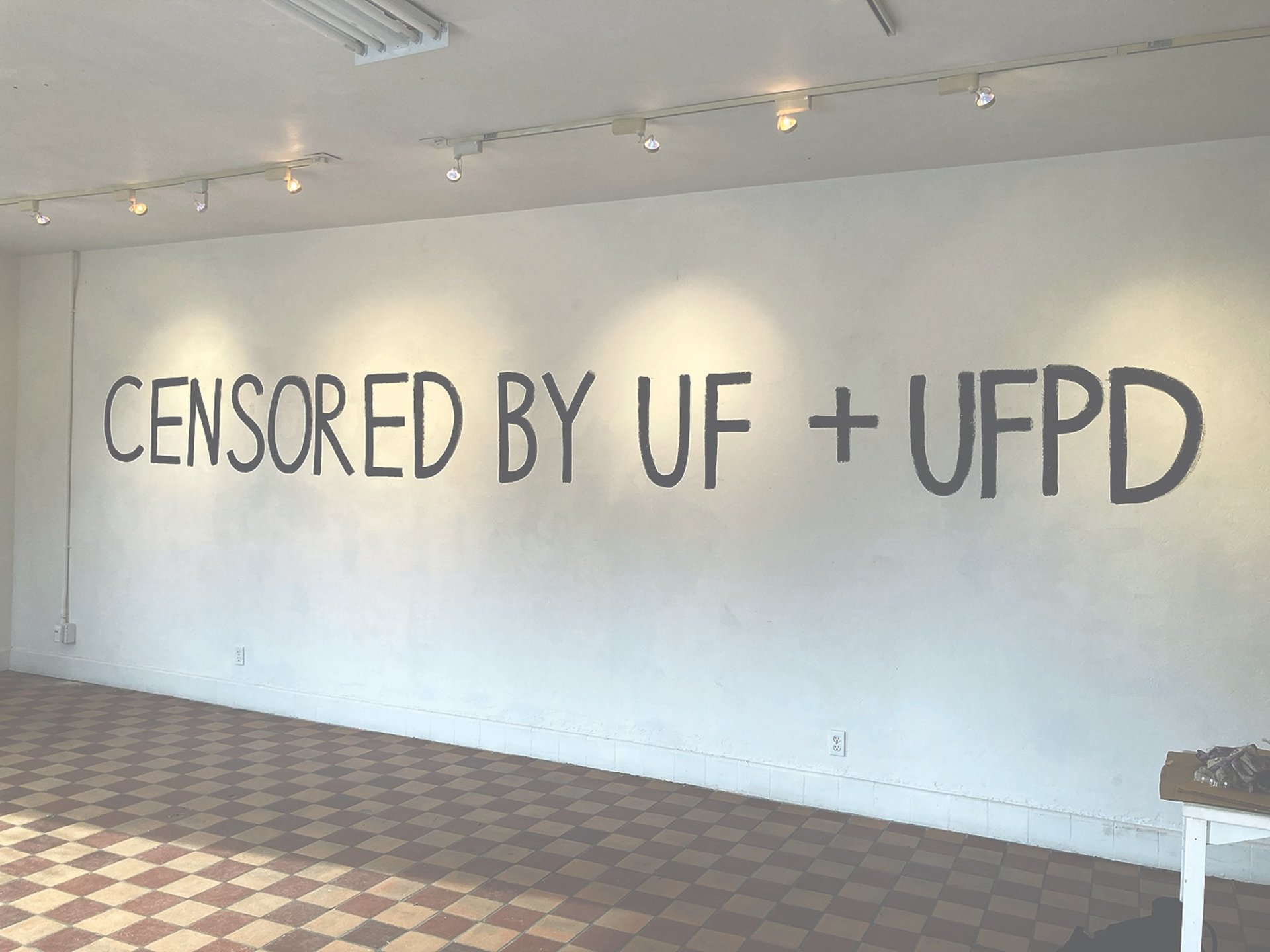

“The next day, I had students who were afraid of going in to take a class at the gallery,” says Angela DeCarlis, a UF art professor. Nevertheless, the gallery decided to rearrange the exhibition, emptying out the show but displaying the rocks used to vandalise the gallery, the windows’ shattered glass, and the censored banners (now returned to the gallery). The words “censored by UF + UFPD” (University of Florida Police Department) were painted on one of the blank walls.

After the University of Florida's Burn It Down exhibition was forced to remove external banners, organisers pivoted, adding a statement to a wall and displaying rocks thrown through the gallery's windows Photo: Courtesy Burn It Down

DeCarlis, who also curates exhibitions at the Thomas Center, a historic building in Gainesville run by the city, says of the political climate: “We now need to be strategic about what art goes on the walls. The discussion we are having is, how can we promote political art without having a gallery shut down?”

Repercussions of DeSantis’s education laws have also been felt beyond the UF campus. In June, DeCarlis organised a figure-drawing workshop for trans and non-binary youth as part of their studio Figure on Diversity. After the UF newspaper, The Independent Florida Alligator, published a story in support of the workshop, right-wing media outlets began to target and mock its organisers and participants.

“It was scary,” says DeCarlis. “This is really about the attack on education and the assumption by right-wing media that higher education pushes leftist agendas; someone was specifically trolling university newspapers for these kinds of stories to target.”

Teaching around the law

Across the state, public colleges and universities now have to align their core requirements with Florida’s new legislation. Rebecca Friedman, a history professor at Florida International University (FIU) and the founding director of Wolfsonian Public Humanities Lab, is involved in the committee tasked with implementing the new rules at the behemoth Miami-Dade County institution. Optimistic that it will not negatively affect her teaching, she thinks there is enough latitude in the law’s language for faculty to work around it and still comply with state regulations. “Am I happy about this? No. Do I think it's going to transform how we teach? I don’t think it has to,” she says.

However, the lack of clarity in the law’s language could push faculty to self-censor. “If I were to take out the topics that are concerning to the state, that would already limit what I teach,” says the FIU English professor Vanessa Kraemer Sohan, who specialises in feminist rhetoric. “Faculty morale has been affected. We are doing everything possible to help our students succeed, but layering the new legislation with these attacks on academic freedom is making teaching harder.”

I am in a state where diversity, equity and inclusion has been weaponised and attackedAngela DeCarlis, art professor at the University of Florida

Back in Gainesville, DeCarlis, who is open at UF about being non-binary, has observed that professors feel the need to “camouflage” their curricula. “The work I do advocating for more diverse figure models is DEI, but I am in a state where this term has been weaponised and attacked,” they say.

Ripple effects

While only public colleges and universities are required to implement DeSantis’s education laws, the effects extend to private universities. Throughout Florida, it has become increasingly challenging to hire new faculty at any college. A recent survey by the United Faculty of Florida union reveals that academics from Texas, Georgia and North Carolina are unwilling to relocate to a college or university in the Sunshine State, public or private.

In October, the Rollins Museum of Art, part of the private liberal arts school Rollins College, opened an exhibition titled The Voice of the People: Freedom of Speech. “Had this been at a public university, I don’t think we could have done that,” says the museum’s director, Ena Heller. Yet the political climate has still affected the museum. Last year, the Rollins started a professional development programme for public school teachers to guide them on engaging with the LGBTQ+ artists featured in the museum’s collection. But then, the “Don’t Say Gay” bill passed into law, so the museum decided to try a focus group first to see if teachers could even use the curriculum in their classrooms. While in previous years, such a workshop would have brought in plenty of attendees, this time, not one person showed up.

“I grew up under Communism,” says Heller, who was raised in Romania. “I know what censorship, book banning and minimising freedom of speech means in a society, and I see the signs here in Florida.”