In the 1950s and 1960s, Coenties Slip was a vestige of old New York at the tip of Manhattan, overlooking the East River and in sight of the Brooklyn Bridge. Ignored by the neighbouring financial district—especially at night, when it was dark, quiet and mostly populated by often drunken seamen and homeless people—it was a “strange country within the city, the ‘down downtown’”, as Prudence Peiffer notes.

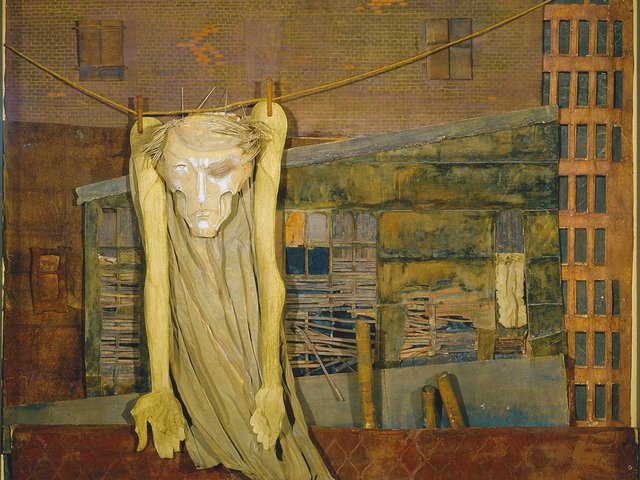

For a few years the 19th-century warehouses on this street—already dwarfed by encroaching skyscrapers and soon to be demolished to make way for more—were the studios and (illegal) homes of a group of artists. They began life there as unknown misfits but left with burgeoning reputations, and some with art-world fame. The Slip: The New York City Street that Changed American Art, Peiffer’s richly researched and evocative book, captures those years through the lives and work of the artists Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Lenore Tawney and Jack Youngerman, and the actor Delphine Seyrig. Among those playing cameo roles are Alexander Calder, Barnett Newman, John Cage and Louise Nevelson.

But the Slip itself is as much the subject as the artists who, by seasonal turns, shivered and sweated in those atmospheric studios. Once occupied by shops, dealerships and sail-making workshops, Coenties Slip was named loosely after Dutch colonial settlers, and among the busiest and noisiest ports in the US. It was name-checked by Herman Melville in Moby Dick, a resonance some artists built into their work.

[It was not about] a movement and its manifestos [but] about being together in a very specific place at a very specific timePrudence Peiffer

Peiffer, a former editor at Artforum magazine and now at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, writes that thinking of artists in terms of place allows for a “more inclusive” art history, which can “bring in the small details around the conditions and materials of working…that help uncover why anything gets made at all”. Indeed, she uses those details brilliantly to weave together the Slip and its inhabitants, reflecting how the historic culture and fabric of this obscure metropolitan corner, the near-derelict piers at its end and the river beyond, infused and enriched the artists’ work and gave them the space and time to find their distinctive languages.

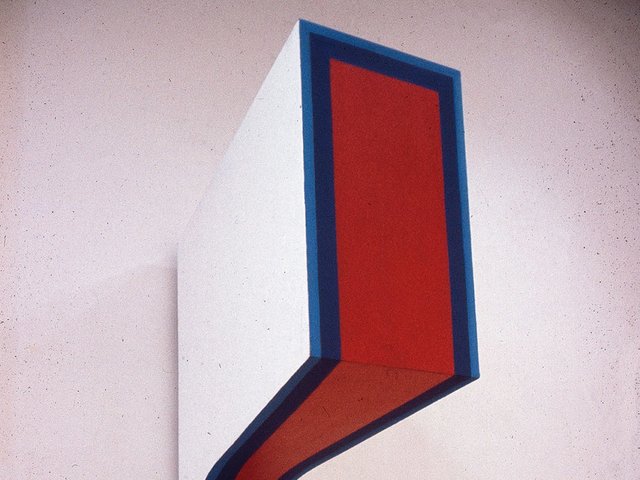

Take one example: Indiana and Kelly were briefly lovers, and once shared an orange on the “rickety wood of Pier 7”. Kelly kept the peel, traced it and drew it, eventually making Orange Blue (1957), a marvellous small abstract, which he gave to his lover in memory of that moment. Peiffer describes beautifully Kelly’s ability to absorb visual information, and his complex notions of nature, which he once described as “everything seen”, and might include anything from the plants he surrounded himself with—including the avocados that “everyone at the Slip had”—to the vaults on a cathedral. “I want to work like nature works,” he said.

Kelly’s journey to success was more inevitable, it seems, than most of his neighbours, especially Youngerman (quietly, the hero at the heart of the book) and Indiana. The latter duo even set up an ill-fated art class on the waterfront. Agnes Martin’s years on the Slip resulted ultimately in her reaching the sublime, serene grids that make her probably the most revered of all these artists today, but her journey was fraught, full of work she took a knife to and of periods of inactivity due to her then undiagnosed schizophrenia, which prompted long walks across Brooklyn Bridge.

A letter from Martin to Tawney evokes the bonds within the group. It may have been written after Tawney gave a Martin painting she had bought, which might otherwise have been lost in a destructive bout, to the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1963: “You have made this day the turning point of my life,” Martin wrote. Tawney herself had depression, but pioneered new weaving techniques that led to great acclaim and a central role in the key show Woven Forms at what is now the Museum of Arts and Design in New York.

The book’s key theme is the title of Peiffer’s afterword: “collective solitude”, a creative model not about “a movement and its manifestos” but “about being together in a very specific place at a very specific time, without denaturing each individual, locked-away story”. Most of the buildings have gone, but the work remains. When Kelly and Youngerman featured in the prestigious 16 Americans show of new art at MoMA in 1959, a major early moment for them both, it is no coincidence that both submitted works named after the street that proved a remarkable crucible for their art.

• The Slip: The New York City Street that Changed American Art Forever, Prudence Peiffer. Harper Collins, 435pp, $38.99 (hb), published 1 August