Michael Powell (1905-90) and Emeric Pressburger (1902-88) created 19 feature films through their production company, known from 1943 as the Archers—its logo (the equivalent of the roaring lion of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer) an arrow thudding into a target’s bullseye. The first and last productions, The Spy in Black (1939) and Ill Met by Moonlight (1957) are now little known beyond the enthusiast. Yet, in between, this extraordinary partnership produced some of the most influential films in the history of cinema—The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948)—inspiring the likes of Derek Jarman, Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese. In 2022, six films from the Archers stable appeared in Sight and Sound magazine’s “Greatest Films of All Time” poll, a record matched only by Alfred Hitchcock.

Throughout Powell and Pressburger’s work, ‘a clear sense of magic underlies the authentic textures of everyday life’

Often described as quintessentially British, these films were in fact the product of the Englishman Powell’s direction blended with the writing of Pressburger, a Jewish Hungarian who had fled Nazi Germany. Also key to the Archers’ distinctive aesthetic—Powell believed “film is essentially visual”—was a pan-European team of collaborators: the cinematographer Jack Cardiff, pioneer in the use of Technicolor and inspired by Vermeer and Caravaggio; the production designer Alfred Junge, whose controlled elegance had a significant impact on early films such as A Matter of Life and Death; the production/costume designer Hein Heckroth, who introduced a painterly, surrealist style, evident in the fairy-tale-inspired ballet melodrama The Red Shoes (both Junge and Heckroth, like Pressburger, came to Britain as political émigrés); the art director and production designer Arthur Lawson; the matte artist and special effects technician W. Percy Day, who, through painted glass, smoke and mirrors, realised Junge’s pen and wash visions for the Indian Himalayan setting of Black Narcissus without leaving Pinewood Studios in Buckinghamshire; and a regiment of sketch and storyboard artists, tasked with developing initial ideas and the specific tone of each production, including and notably Ivor Beddoes, a dancer, actor and one-time war artist in North Africa.

Celebrating The Red Shoes

The Cinema of Powell and Pressburger is a richly illustrated book that accompanies a brilliant free exhibition celebrating the 75th anniversary of The Red Shoes, now at the British Film Institute (BFI) Southbank (until 7 January), including production material from the BFI collections, particularly the archives of Powell, Pressburger and Beddoes, alongside significant loans, not least the actual red shoes lent by Scorsese. Meanwhile, the film screening series “Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds of Powell and Pressburger” continues across the UK until 31 December.

In their introduction, the editors Nathalie Morris (a curator and writer on cinema) and Claire Smith, the BFI’s senior curator of special collections, observe that throughout Powell and Pressburger’s work “a clear sense of magic underlies the authentic textures of everyday life”. The first years of their formal association coincided with the heightened reality of the Second World War, during which they made films that side-stepped jingoism while still functioning as morale-boosting propaganda. Yet where, for example, David Lean’s This Happy Breed (1944) acknowledged the recent experiences of stoical Londoners, Powell and Pressburger’s patriotism was altogether more romantic and soulful, with ordinary Britons moving through recognisable national history, topography and landscape—such as Kent in A Canterbury Tale (1944) and the Hebrides in I Know Where I’m Going! (1945)—while encountering the mythical, fantastical and spiritual.

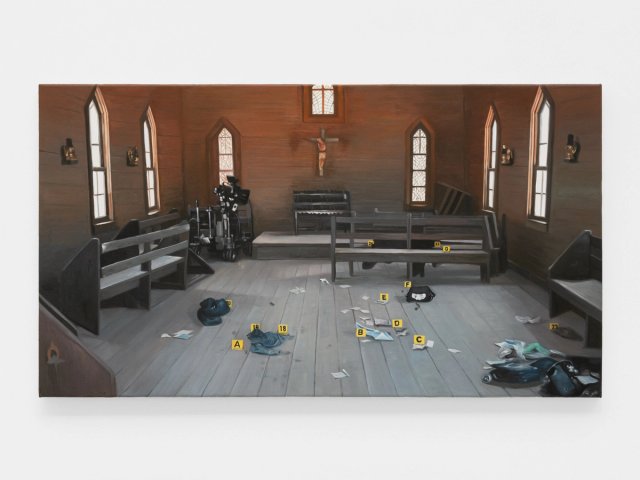

“Controlled elegance”: Alfred Junge’s Stairway to Heaven production design for Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death (1946)

Alfred Junge Estate © ITV Cinematheque francaise

In A Matter of Life and Death, Peter, a British RAF pilot, speaks to June, an American radio operator, over the airwaves just before his damaged Lancaster bomber crashes. In those minutes they bond, as individuals and as a metaphor for the UK-US special relationship. Peter accidentally survives, so must put his case for life over death before a judge, barristers and jury made up of historical figures in Heaven—a black-and-white “expressionist” vision, in contrast to the glorious Technicolor of Earth (England), reached by a giant escalator inspired by William Blake’s Jacob’s Ladder. Humanity, fellow feeling and, of course, love conquer all.

The publication is divided into six chapters, four themed—“Exiles”, “Pilgrims”, etc—and spanning the Archers’ output. Two chapters focus on a single film: Mahesh Rao’s personal and conflicted response to the racial and sexual tensions in Black Narcissus; and Marina Warner on the origins of The Red Shoes within the macabre fables of Hans Christian Andersen. Further short contributions explore the Archers’ impact on 21st-century practitioners including the photographer Tim Walker, the artist Michelle Williams Gamaker and the film director Joanna Hogg. The BFI’s collections are showcased in full colour, with further material from La Cinémathèque Française.

Beddoes is a revelation. As Morris and Smith observe, his myriad drawings and designs “chart the many hands and minds involved in production and show how the Archers’ definitive statements on art were built on a paper premise”. Production sketches, they continue, are both “personal musings” and “collective tools of communication within the studio system”. Alongside the films themselves, this splendid book is testament to a unique creative collaboration.

• The Cinema of Powell and Pressburger, by Nathalie Morris and Claire Smith (eds). British Film Institute/Bloomsbury Publishing, 206pp, 250 colour illustrations, £30 (hb), published 5 October