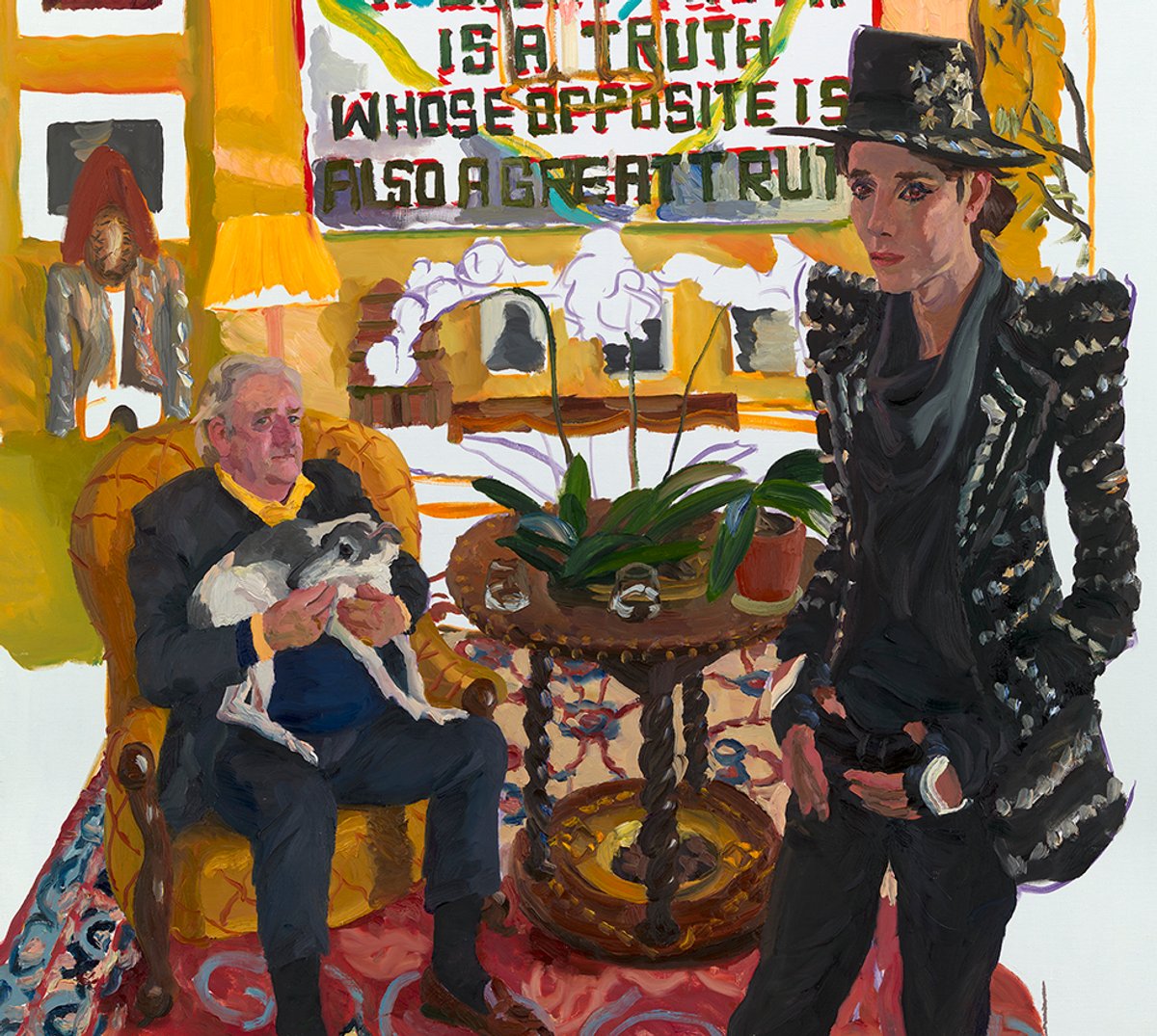

Over his three-decade-long career, the Chinese figurative painter Liu Xiaodong has told countless stories of migration. From Syrian refugees in Turkey to Chinese textile workers resettled in Italy—each work is a tale of displacement that focuses on how people relate to their newfound environments. But what of the international elite, whose jet-set lives render them virtually stateless? In New England at Massimo de Carlo (until 21 November), Xiaodong turns his eye to wealthy ethnic Chinese immigrants now relocated in London. The show's eight portraits, all painted last year, depict upwardly mobile sitters in glamorous surroundings. They play polo, pose in Missoni jumpsuits and recline naked in Rococo chaise lounges, all rendered in Xiadong's typically loose, impasto style. In an accompanying documentary film they speak of shared anxieties over assimilation and alienation in their new communities. These are ambitious, foreign settlers who have taken their agency into their own hands. Yet in their search for success they now embody the vestiges of a dying empire—one which they can never truly claim as theirs. Continuing Xiaodong's long-standing project to portray "the subject of lives driven by the current", these paintings undermine the notion of solid identities in the age of globalisation and question what people sacrifice in their quest to find a home.

Installation view of Ugly Plymouths at Sadie Coles HQ, Cork Street © Sadie Coles HQ

Bathing Sadie Coles HQ's Cork Street pop up space in red light, Martine Syms's installation Ugly Plymouths (until 31 October) provides a dramatic setting for quotidian content. First shown earlier this year in Los Angeles, it presents a "three-part play" consisting of footage from the artist's life, simultaneously shown across three separate screens. Shot entirely on an iPhone over the course of several years, before then being processed through a Super 8mm film camera, it contains no discernible narrative. Voices speak over one another and characters slip in and out of frame with little context. Ten seconds of a Nicki Minaj concert is followed by grainy shots of the sea and then an afternoon walk along a street. Pops of red—roses, Syms's cherry-coloured braids and the embers of a joint she smokes in a selfie—are all that is provided to anchor the visual experience. Fairly soon, however, you become more content with this aimless flow, noticing how the camera zooms and pans according to the motions of Syms's body—her hands are almost as evident here as if we were witnessing their marks on a physical object. Speaking to "troubled connections", the work is remarkably current. Not only for its authentic portrayal of daily American life, but in its insistence that a collection of unremarkable experiences is worthy of our focus. With no further explanation needed.

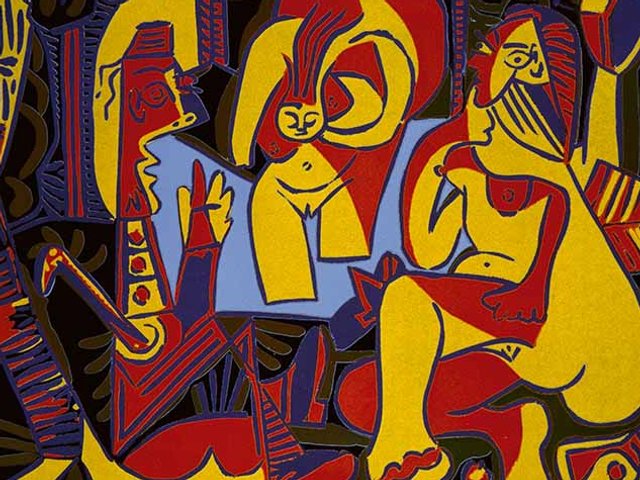

Installation view of the Royal Academy of Arts's Summer exhibition Photo: © Royal Academy of Arts / David Parry

The Royal Academy of Arts's (RA) annual Summer Exhibition (until 3 January 2021) may have been delayed for the first time in its 250-plus-year history—but this bastion of the British art world has maintained its stiff upper lip and the show has gone on. In a wise and generous move, the show's artist-curator duo Jane and Louise Wilson have given over the first two rooms to the fellow Royal Academician Isaac Julien, who has curated an exhibition devoted to the memory of the Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor, who died in March 2019. Here the gauntlet is laid down by the fact that every artist in these galleries—except for Peter Doig—is Black. There’s a dramatic pair of Wangechi Mutu's looming totemic figures and a giant Zanele Muholi self portrait which presides over a gorgeous Chris Ofili triptych, a Theaster Gates firehose abstract and arresting works by Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Glenn Ligon and Frida Orupabo. One of Yinka Shonibare’s globe-headed mannequins seems buffeted by forces beyond her control and an early composite black-and-white photowork by Julien is devoted to the protests around the killing of Colin Roach, who died from a gunshot wound outside Stoke Newington police station in East London in 1983. A stark reminder that today’s struggles and protests are nothing new. Let’s just hope that the RA—and the wider world—regards this year's exhibition not as a token gesture, but as a manifesto for the future.