Among the most intriguing objects in the British Museum is the Asante Ewer, a bronze jug made in England for Richard II in the 1390s, which somehow ended up in West Africa. In January 1896 the ewer was looted by UK troops from the Asante (Ashanti) king, in what is now Ghana, and returned to London. Six months later it was sold to the museum. So, what is the object’s current ethical status? Could it possibly have been looted twice?

The mystery is how the ewer reached the Asante capital, Kumasi, which is around 5,000 miles away. There were two possible routes. It may have travelled on an English ship to North Africa, from where it could have been sent overland by camel, across the Sahara to Timbuktu and then on to Kumasi. Alternatively, it may have gone by sea, possibly as early as the 1470s on one of the first Portuguese voyages around West Africa.

The Asante Ewer has a lid decorated with stags, sides engraved with eagles, and the front with the royal arms of England

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The British Museum is now investigating the story of the Asante Ewer, as part of a project to examine early connections between England and West Africa. In recent years this relationship has been studied primarily in terms of the slave trade, but the museum also wants to delve deeper into earlier links.

The project, funded by the British Academy/Wolfson Foundation, is expected to lead to an exhibition or display centred around the Asante Ewer, to be held at the British Museum and Leeds City Museum (which has a smaller ewer, also looted from Kumasi). This will probably be held in 2025-26, when the British Museum curator Lloyd de Beer is publishing a scholarly book.

Highly valued

The imposing lidded Asante Ewer, 62cm tall and weighing 22kg, is much too heavy to have ever been used for pouring liquids; it was probably a prestige object made for display. Casting such a large bronze ewer would have required great skill.

The ewer is ornately decorated. Beneath the spout are the royal arms of England, as used from 1340 to 1405. But the ewer can be dated more precisely, since the stag decorations on its seven-sided lid represent the personal emblem of Richard II, suggesting that it was cast during his reign in the 1390s. A three-line inscription in relief lettering (translated into modern English) ends: “Deem the best in every doubt until the truth be tried out.”

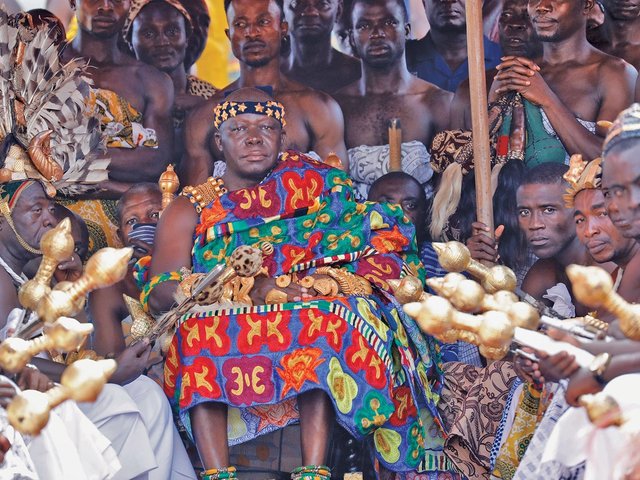

This 1884 photograph of the royal compound in Kumasi in modern-day Ghana shows the Asante Ewer and a smaller vessel, which is now at Leeds City Museum

Foreign and Commonwealth Office Library

An 1884 photograph, taken over a decade before the looting, shows the Asante Ewer and the smaller vessel (now in Leeds) under what was probably a sacred tree in the courtyard of the royal compound in Kumasi. The presence of the two prominently displayed English ewers suggests that they were then highly valued by the Asante rulers.

The Asante Ewer was seized when British troops ransacked the Asante king’s compound in Kumasi during the Anglo-Ashanti Wars in January 1896. It was acquired by a senior officer, Charles St Leger Barter, who sold it to the British Museum for £50.

“I was fortunate enough to secure it from the officer to whom it fell”

Charles Read, then the museum’s keeper of British antiquities, described the ewer (in the language of the time) as “among the paraphernalia of a negro king”. He added: “I was fortunate enough to secure it from the officer to whom it fell. He had the perspicacity to prefer the ‘old jug’ to the ordinary savage weapons and blood-stained sacrificial stools”.

Along with the Asante Ewer, two other smaller and simpler jugs were also looted by the British at Kumasi. These two are similar to each other, suggesting that they were cast in the same foundry. Since all three ewers ended up in West Africa, it is likely (but not certain) that all came from England’s royal household. A technical examination of the three, including their metal composition, is now planned.

“It was the great war fetish of the Ashanti Nation, always taken into battle”

The smaller ewer that appears in the 1884 photograph was acquired by the governor of the Gold Coast (as the territory was then known) during the 1896 military operation and was immediately presented to West Yorkshire Regiment officers. It later passed to York Army Museum and is on long-term loan to Leeds City Museum.

The third ewer was acquired by the British Museum in 1933 from Cecil Hamilton Armitage, who fought in the Anglo-Ashanti wars of 1896 and 1900. A museum publication at the time of the acquisiton records that it was “the great war fetish of the Ashanti Nation, and was always taken into battle”.

Mysterious voyage

Although the ewers may have been sold or stolen from England’s royal household, they are more likely to have been dispatched as diplomatic gifts. They probably left London in the 15th or 16th centuries.

The puzzle remains: how did the ewers reach Kumasi? If diplomatic gifts, there would have been little reason for English kings to have wooed the Asante at this early stage, before it became a great kingdom. But the ewers could have been a gift to a North African ruler, whose successors subsequently sent them across the Sahara.

Alternatively, the ewers might have been acquired by traders and taken to West Africa by sea. Portuguese ships began to explore the Ghanaian coast from the 1470s. It is just possible that they first reached Lisbon through Philippa of Lancaster, who was born into the English royal family and became queen of Portugal in 1387.

If the ewers had remained in the UK many years later, then English vessels began arriving in West Africa from the 1540s. The large-scale trade in enslaved people through Ghanaian ports only began in the 1600s and the ewers probably arrived well before then.

Sold or stolen?

The present ethical status of the ewers is complex. Although looted by the British in 1896-1900, they came from England. It remains unclear whether they left the household of Richard II in proper circumstances or were stolen. However, once they reached West Africa, it is very likely that they were given (or possibly sold) to a powerful figure in what is now Ghana, as a legitimate acquisition. Since the Asante kingdom was only formed in the early 18th century, the ewers might well have been brought to Kumasi from another West African group, possibly as the spoils of war.

The Asante Ewer is at present displayed in the British Museum’s medieval gallery, although the smaller ewer is not on show. The two were together in 2020-21 in the exhibition Caravans of Gold: Fragments in Time: Art, Culture, and Trans-Saharan Trade, presented in Washington, DC; Toronto; and Evanston, Illinois. The Yorkshire ewer is at present on display in Edinburgh, in the National Army Museum’s exhibition Legacies of Empire (until 21 January 2024).

The 2025-26 London and Leeds display will be the first opportunity to see all three vessels together. Hopefully, De Beer’s research will get closer to solving the mystery of how these 700-year-old ewers reached West Africa.