The incandescent images of Daido Moriyama—the punk king of Japanese photography—are now on show in London’s Soho. The photographer’s work fills the main exhibition spaces at the Photographers’ Gallery, in what is a rare retrospective spanning the entirety of his 60-year career.

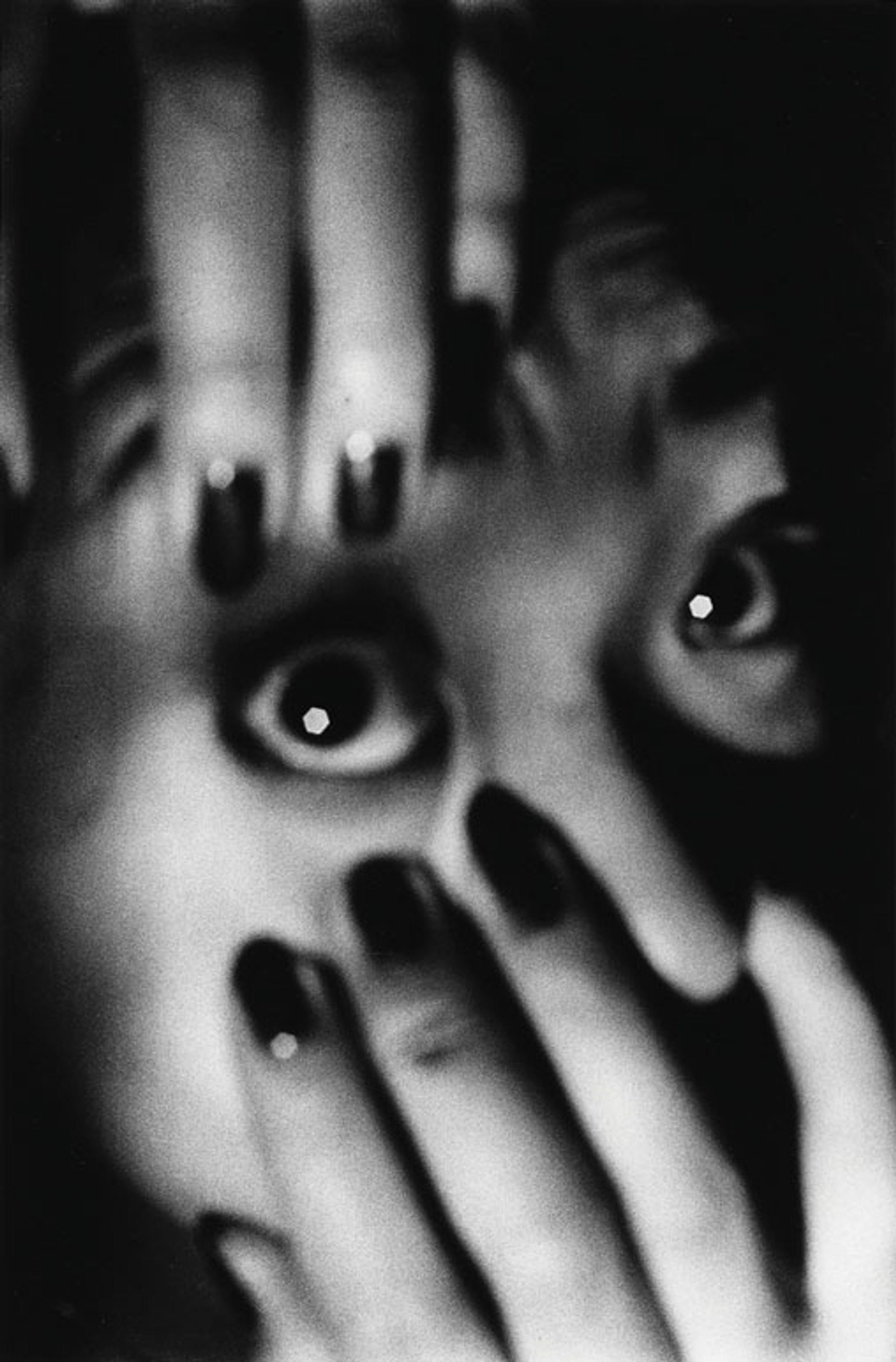

Moriyama’s raw, saturated images of the neon-lit backstreets of Tokyo, taken on a simple compact camera, are legendary. Writing in Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde, the art historian Yuri Mitsuda described the photographer’s images as “grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus”.

This visual language is now almost overfamiliar, and much copied. Work by Moriyama is a regular feature of photography fairs. His style is often mimicked by photography students of the day. But the retrospective at the Soho institution offers followers something different, showing—often for the first time in the UK—many of Moriyama’s earliest experiments in magazine and photobook publishing.

An image from Moriyama's Letter to St-Loup (1990) © Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Why is this significant? Because Moriyama’s work was arguably at its most potent when he was an unknown street photographer, his images reflecting on the tumultuous and progressive movement of which the artist is a standard-bearer, the so-called taiyozoku or “sun tribe” that came out of Japan’s traumatising experience of the Second World War.

The taiyozoku were West-facing. They were enamoured with the Beatniks, The Beatles, New Hollywood cinema and American consumer culture, and they were dismissive of Japan’s obsession with its own cultural history. Older generations viewed the sun tribe as nihilistic and unworthy. This culture war was underpinned by the actual war; some of Moriyama’s earliest memories are of the firebombing campaign that devastated Japanese cities like Osaka, where the artist was born in 1938.

After dropping out of a graphic design course, Moriyama began assisting Japanese photographers who took rigorous formal pictures of flowers, gardens and landscapes. After moving to Tokyo, he began to attend meetings of Vivo, a group of determinedly avant-garde photographic artists. Moriyama met the group’s founder Shomei Tomatsu shortly after he had published, along with Ken Domon, the book Hiroshima–Nagasaki Document 1961, an expressionist inquiry into the social impact of the atomic bombs.

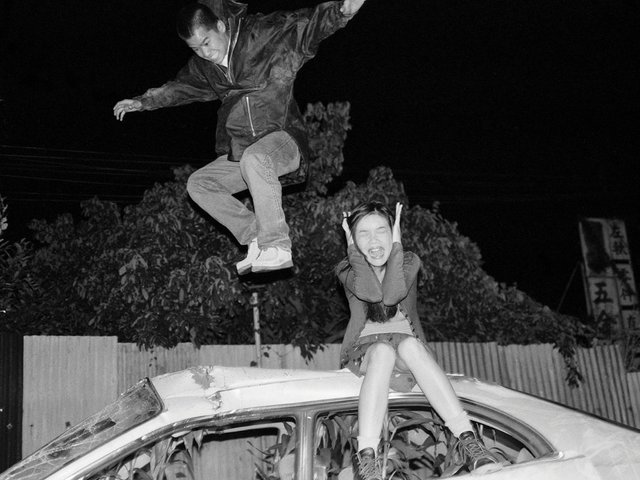

Moriyama's Tokyo, (1969) from the Accident, Premeditated or not series © Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Tomatsu and Vivo’s other doyens taught Moriyama about processing and developing; about editing and sequencing; and about the artisan demands of binding and publishing. He learned how each of these skills can heighten and deepen the meaning of what, in isolation, can appear to be a random image with little overt significance. Moriyama, then, learned to harness his nation’s preservationist culture even as he strived to reject it. Japanese art has a long history of craftsmanship with paper—from origami and woodcuts to linocuts and calligraphy. As Moriyama and his contemporaries pushed at the edges of what photography could be, they channelled, in new ways, a cultural legacy that was distinctly Japanese.

In the late 1960s, Moriyama was centrally involved in the creation of the photography magazine Provoke. The publication only ran for three issues and was printed in small editions of 1,000. Today, copies can change hands for more than $20,000; the editions on show in this exhibition, then, are among the most influential photography magazines one can see. The magazine did exactly what its title promised: it acted as a direct provocation to traditional Japanese values. It was explicit, lascivious, political and garish. It called on its readers to “leave the world of certainty behind”.

Provoke became a showcase for a historic disregarding of the stately objectives of traditional documentary photography. Its photographers were resolutely interested in expressing, subjectively, the dialectics of Japan’s post-war reality: a deep sense of tumult, change and disruption, a youthful rejection of social repression, captured with an abraded, kinetic energy. The publications quickly became a source of fascination for Western photographers after being exhibited in New Japanese Photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1974.

Stray Dog, Misawa (1971) from A Hunter © Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Moriyama’s experience on Provoke pushed him further into self-publishing his own collections of street photography. He threw himself ever deeper into the streets of Shinjuku, now a hip, commercial centre of Tokyo, then a crime-ridden warren of foreboding backstreets. Moriyama’s images of Shinjuku were saturated to the point of appearing still wet with chemicals, and grainy to the point of abstraction. They seemed almost hallucinatory, as if the photographer was gripped by a fever dream.

In the gallery, visitors should pay special attention to Moriyama’s 1972 publication Shashin yo Sayonara (known as Farewell Photography), an almost complete eschewal of traditional ideas of ‘good’ composition and aesthetics. Some of the photographs were burnt and peeling, abstracted by spills in the dark room—a conscious act of destruction. Writing of the series, the art critic Minoru Shimizu called Farewell Photography “a method of annihilation: no meaning, no expression, no sense of the photographer”. Perhaps so. And yet, in embracing chaos, Moriyama became a photographer who transformed the history of the medium, and changed the way the world views the coiled multivalence of his nation.

• Daidō Moriyama: A Retrospective, The Photographers’ Gallery, London, until 11 February 2024