The pervasive presence of trees and forests has been a staple in German art, literature and music throughout the centuries: from the forests of Albrecht Altdorfer’s early Danube landscapes through to the 19th century and Caspar David Friedrich, the folk tales of the Grimm brothers and Franz Schubert’s Lindenbaum. The status of national material to which wood came to be elevated at this time would, though, lead to the appropriation by the Third Reich of these cultural and historical roots, in its new mythologising of the German “race”.

In this interesting and original study, Gregory Bryda, an assistant professor of art history at Barnard College, Columbia University, New York sets out to explore the significance of the material of wood in the consciousness of late Medieval Germany, as expressed through art, folklore and Christian ritual and teaching. Although other scholars have written on the practice of wood sculpture in Germany, notably (in English) Michael Baxandall in his seminal The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany (Yale University Press, 1980), the author here seeks to show how wood as a material became an integral element in liturgical ritual to a far greater extent than elsewhere in Europe.

In the 14th century, in the carved and painted wooden crucifixes of the type known as Crucifixi dolorosi or doleful crucifixes, the suffering of Christ was accentuated through graphic depictions in wood of his tormented body, while the crosses, forked, knotted and painted green, seem to sprout from the very ground. Also first seen in the 14th century, but reaching their apogee in works such as Tilman Riemenschneider’s Holy Blood Altarpiece (around 1500-05) in the church of Saint Jacob, Rothenburg, are enormous elaborately carved wooden altarpieces and sacrament houses that, towering upwards like celestial trees, appear to grow from out of the floors of their churches.

Sculptural works, but also paintings, prints and manuscripts, many little-known, are employed by the author for his wide-ranging narrative, which moves from complex theology to popular folklore.

The book is structured into four lengthy chapters, preceded by an introductory essay and with a short epilogue examining the impact of the Protestant Reformation. The first chapter, The Vegetable Saint, discusses a series of graphic doleful crucifixes, such as the one first recorded in 1304 in the church of Santa Maria im Kapitol in Cologne. Some, notably the early 14th-century crucifix from Kranenburg in Cleves in north-west Germany, in which the figure of Christ appears uncarved and almost formless, are of poor quality by normal aesthetic standards, so as a result have been neglected by art historians.

The Cross as Tree of Life

Wooden crucifixes formed an intimate element of the complex story of the True Cross as told through popular sources such as the Golden Legend, according to which the wood of the cross on which Christ was crucified originated from a tree that grew from a twig taken from the Garden of Eden. The True Cross was linked to the parallel concept of the Cross as the Tree of Life, which in turn connected with Christ’s family tree, the Tree of Jesse, from representations of which the Virgin and Child emerge in two remarkable altarpieces, in Erbach and Amorbach.

With this context, it is no surprise that German medieval crucifixes often boasted miraculous origins rooted in trees, their stories continuing to be venerated to this day. Thus the location of the miraculous oak, within which (according to legend) the roughly-hewn Kranenburg crucifix had formed, was commemorated by a marker, while the crucifix itself is processed through the town each September.

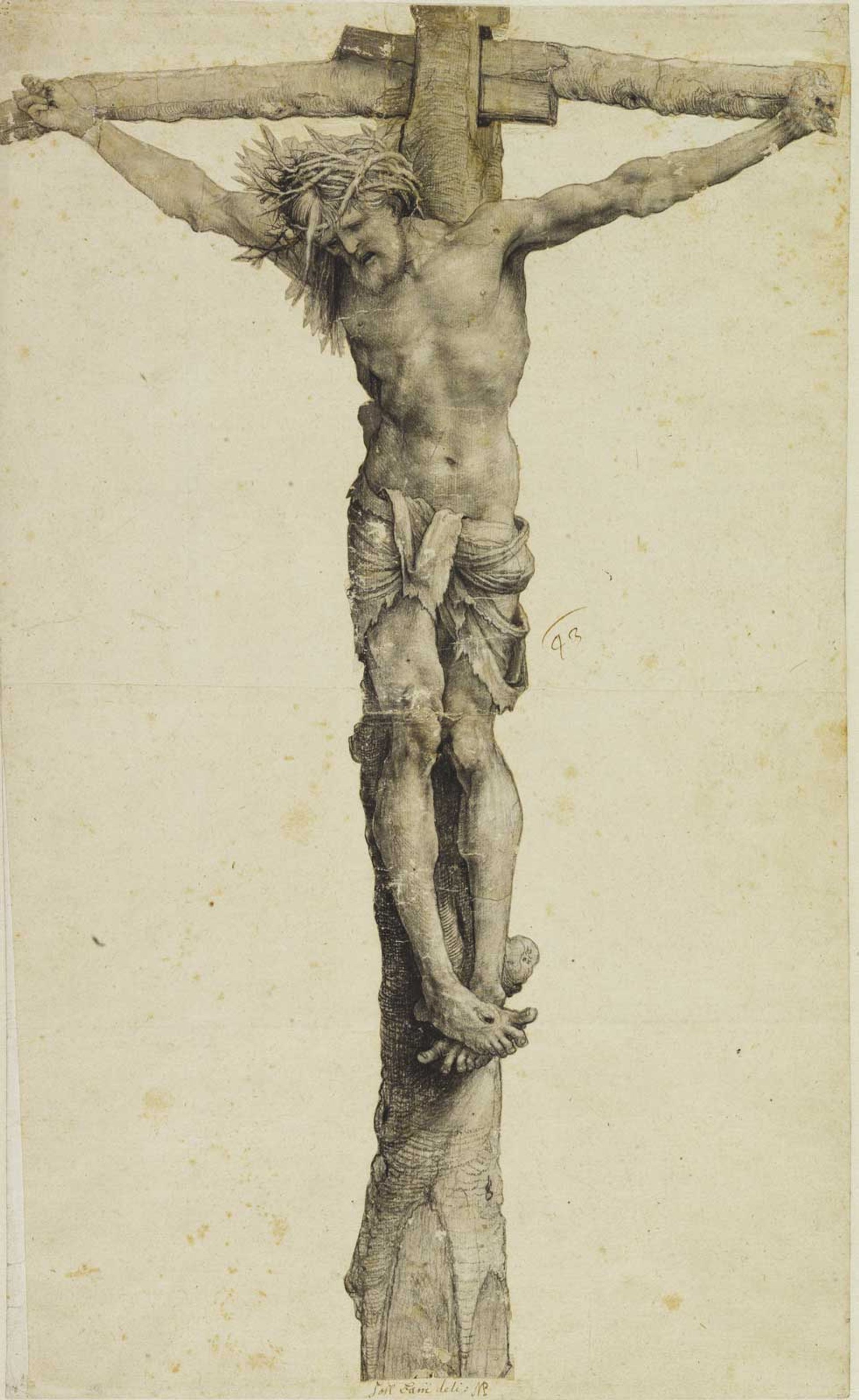

Matthias Grünewald’s exquisite charcoal drawing of around 1520, showing the figure of Christ on a rough-hewn cross

© Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe/Wolfgang Pankoke, Elvira Beick

However, other practices more rooted in pagan beliefs, such as the Maytime festivities marking the renewal of the earth after winter, were regarded more ambivalently by the church, as discussed in the chapter entitled The Spiritual Maypole. Maypoles could be seen not only as pagan aberrations but also as mocking perversions of the Crucifixion. The mystic Henry Suso (1295-1366) sought toreconcile the pagan with the Christian through the concept of the Spiritual Maypole, in which nature, in all its variety and vigour, was embraced as part of the journey towards spiritual transcendence, the spiritual May tree being decorated not with pagan baubles such as the mirrors that often adorned maypoles, but with the Arma Christi, the instruments of Christ’s Passion.

Chapter three, Grünewald’s Greenery in Spring and Summer, focusses on two works by the painter Matthias Grünewald (around 1470-1528), the enormous Isenheim altarpiece and the Heller altarpiece, for which Grünewald supplied the outer panels. A trained carpenter, Grünewald evidently delighted in the ultra-realistic depictions of wood in his work, notably the roughly-hewn crosses in his Crucifixion scenes. The cross in the Isenheim altarpiece closely resembles a Tau Cross (T-shaped, resembling the Greek letter tau), the emblem of the Antonite monks who commissioned the altarpiece. The author links the ghastly suppurating body of Grünewald’s crucified Christ and the many plants depicted in his altarpiece with the healing mission of the Hospital Brothers of Saint Anthony, demonstrating how, at this time, for both devotional and scientific writers there was no healing that was not the will of God, thus no real dividing line between the medicinal and the religious.

Wine-making and Christ’s Passion

The fourth chapter, The Spiritual Vintage, examines the significance of another form of wood, the grapevine, in the lives of wine-producing communities such as Rothenburg ob der Tauber, for which Tilman Riemenschneider and the carpenter Erhard Harschner made their extraordinary soaring altarpiece, within the branches of which is held the town’s famous relic of the Holy Blood.

The highly labour-intensive process of growing and producing wine could be seen to parallel Christ’s own Passion, as shown in some remarkable images of the sorrowing figure of Christ being slowly crushed within a wine press. While before the Reformation the drinking of wine was regarded positively, one author even suggesting that drunkenness was a metaphor for sacramental union with Christ, the malign effects of drink would be satirised by Protestant artists just a few decades later.

The short epilogue to the book examines the impact in much of Germany of the Protestant Reformation, with its new emphasis on the Word of God and widespread destruction of idolatrous images. The author shows how, nevertheless, wood-derived images did survive into the Reformation, but in repurposed form. So, in Erhard Schön’s 1532 woodcut God’s Lament for the Fate of his Vineyard, Christ may once again be seen on a cross formed from vine branches, but now the pure water of Baptism flows from a cistern at the base of the Cross while a preacher is shown addressing his congregation. But the main scene depicts the pope and his Catholic followers destroying the vineyard, grubbing up a series of dead trees laden with rosaries, papal bulls and the symbols of the Passion.

It is questionable to what extent, if at all, most artists and artisans in late medieval Germany were conscious of these complex cultural and theological relationships, but their presence throughout the works of art discussed in this book goes to show how trees and woodiness were indeed deeply embedded in the contemporary psyche. A somewhat leaden prose style does not make this an easy book to read, but the fascinating arguments addressed within it result in a rewarding survey that is full of new insights.

• Gregory C. Bryda, The Trees of the Cross: Wood as Subject and Medium in the Art of Late Medieval Germany, Yale University Press, 224pp, 124 colour & 34 b/w illustrations, $75/£60, published 13 June

• Jeremy Warren is the honorary curator of sculpture at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford and author of the museum’s medieval and renaissance sculpture catalogue (2014)