This is the third of three articles. The first part is available here; the second part is here.

Just 30 kilometres east of Eisenach, an exhibition in Gotha triumphantly rounds off a tribute to Cranach with Cranach in Service to the Court and the Reformation (until 19 July). The location is Schloss Friedenstein, one of the most impressive castles built anywhere in the Holy Roman Empire in the 17th century.

Despite its later date, this monumental structure, which dominates the small town of Gotha from its hilltop location, actually has close links with Cranach and the Lutheran tradition. Cranach’s wife was the daughter of a Gotha town councillor and they almost certainly married there. The Cranachs owned a substantial house on the upper main market.

In their day the castle was named the Grimmenstein, but it was razed to the ground after the failure of Duke Johann Friedrich’s sedition in 1567. Following a new partition of the Ernestine lands in 1640, Ernst the Pious set about building a residence, Friedenstein, at the centre of his new duchy of Saxony-Gotha. The new residence was more palace than castle, with a large chapel and the earliest Baroque theatre in Germany. Both should be seen by any visitor.

Duke Ernst brought with him from Weimar a significant collection of Cranachs and set about amassing a huge collection of books and manuscripts relating to the Reformation. Perhaps more than any other Ernestine ruler, he was determined to assert the claims of his dynasty to the guardianship of the Reformation and its legacy. The Cranach collection was the jewel in that crown, the core reliquary in a sense, around which everything else was collected.

Schloss Friedenstein is a largely undiscovered gem, not least because of its troubled 20th-century history. The end of the duchy in 1919 was the prelude to a difficult period of negotiation with the ducal heirs over ownership. In 1945 Soviet forces removed many treasures, including the works of both Cranachs. Twenty-seven of the latter were eventually returned, comprising the largest collection anywhere, but about 17 remain in Moscow along with books and other treasures: the two-volume catalogue of what was lost makes for depressing reading.

Today Schloss Friedenstein has been recreated as a “Baroque Universe”. Under the direction of the dynamic Martin Eberle, director of the Braunschweig municipal museum until 2007, the Schloss Friedenstein Foundation has made huge strides. Despite chronic financial problems, the 19th-century museum has been sympathetically restored and the collections there (and those in the castle itself) have been imaginatively rearranged. The show itself has benefited from co-operation with the Galerie Alte Meister in Schloss Wilhelmshöhe in Kassel, whither it will travel (21 August-29 November). The co-sponsorship of the Land Hessen and the pooling of curatorial resources has resulted in a much more tightly argued presentation. It has also yielded a superb hardbound quarto catalogue, which far surpasses the small-format paperbacks available at Weimar and the Wartburg (Morio Verlag, 366pp, £18.35 hb). The catalogue provides an excellent introduction to the show and it will be essential reading from now on for scholars and others interested in the world of the Cranachs.

In this exhibition, housed in the ducal museum, we can follow a comprehensive chronological survey of Cranach the Elder’s work set in the wider context of the politics of his time with frequent references to his contemporaries: friends, patrons, rivals and adversaries.

We begin with Cranach’s pre-Reformation work for Frederick the Wise. These included altarpieces like the charming winged altarpiece depicting the Ascension flanked by images of Saint Barbara and Saint Catherine. At a more popular level Cranach also produced woodcuts illustrating the Elector’s collection of relics, the largest in the Holy Roman Empire.

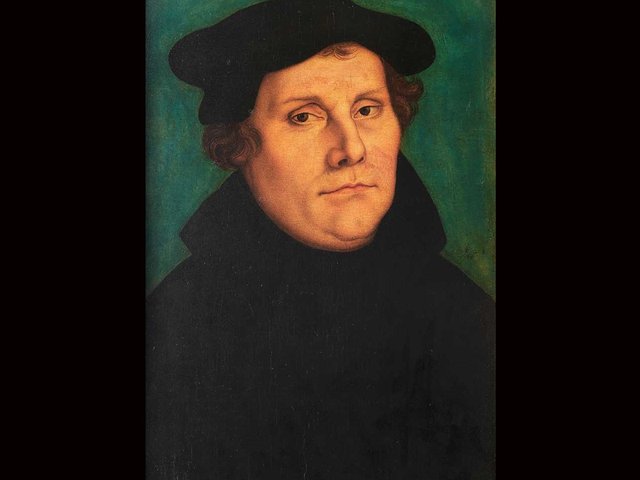

The next section devoted to Reformation propaganda illustrates a radical change of style and demonstrates how rapidly Cranach mastered the new print media. Catholic print makers filled their woodcuts with text to explain the images they drew. Cranach and his collaborators did the same at first, but they soon did away with the texts and concentrated on simplifying the images. The image was the message.

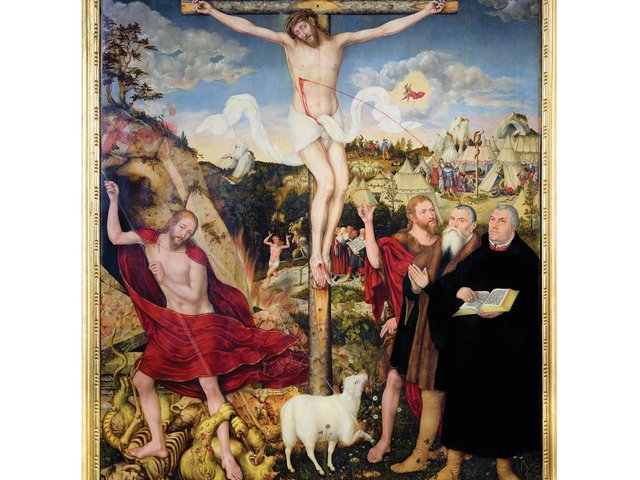

As the polemical strife of the early 1520s diminished and after the upheaval of the Peasants’ War of 1525, Luther’s thoughts focused more on securing the new teaching. Princes and city councils, advised by Luther and other Reformers, sought to restore order and to regulate the affairs of their churches. Cranach supplied the images. The most important was the motif of law and grace that first appeared in print in 1528, then in two painted versions in 1529. One of these has been in the Gotha collection since at least 1659 and is displayed next to its counterpart borrowed for this show from the National Gallery in Prague.

Soon the new Protestant churches needed new illustrations for the old Biblical stories. Again, the Cranachs and their workshop obliged. New interpretations of Jesus and the Adulteress, The Blessing of the Children and Christ as Man of Sorrows underlined the significance of the New Testament, naturally in Luther’s translation, as a guidebook to the Christian life.

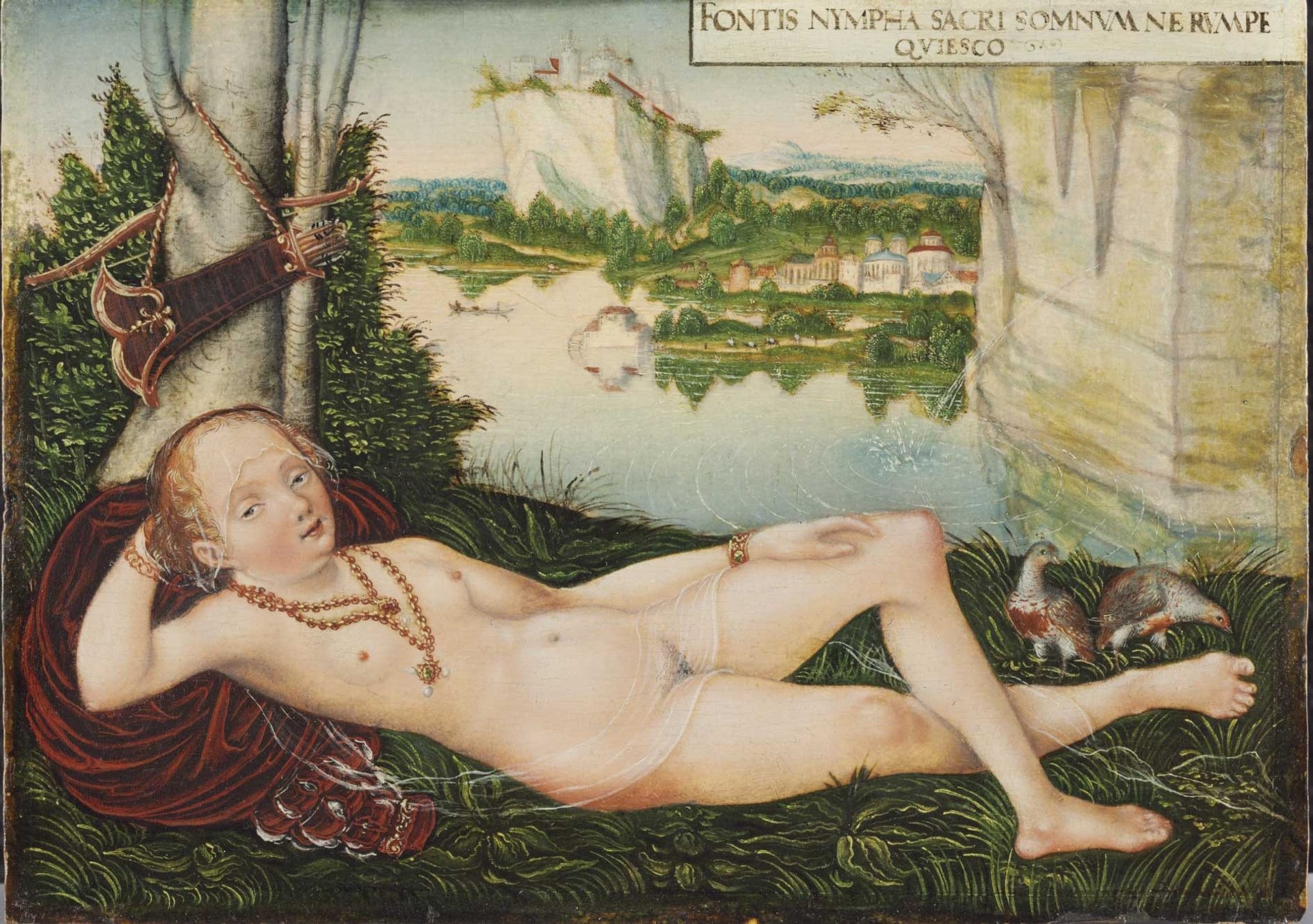

Alongside all this, Cranach still had to supply the needs of the court. Recreational subjects included Venus with Cupid as a Honey Thief (1530) or The Silver Age: Quarrel of the Wild Men and Maternal Solicitude (1527-35), or the charming Resting Nymph of the Spring (1533). Paintings and prints of hunts and tournaments document the life of the court. Official portraits, both of members of the ruling family and of key allies such as Landgrave Philip the Magnanimous of Hessen were also still required on a regular basis.

And being in the service of a prince also required more overt propaganda. The final two sections illustrate Cranach’s war propaganda in support of Johann Friedrich’s struggle against Charles V. A woodcut depicts the journey of the Protestants since the early 1520s as the flight of the Israelites through the Red Sea. In a painting of 1538 the Elector Johann Friedrich is shown in the company of the Wittenberg Reformers (on loan from the Toledo Museum of Art). Woodcuts of 1547, at the height of the military confrontation with imperial forces, depict him as the defender of the Protestant faith.

Finally, even in defeat, images served a vital purpose. Portraits showing Johann Friedrich’s prominent facial injury aroused sympathy for the captive Elector. Indeed Cranach the Younger used the image to portray him in 1552 as a Christian martyr: seated at a table wearing a ducal cap and holding a book, opposite a crucifix, his prominent left-side wound juxtaposed to that on Christ’s right side.

Together the Thuringian Cranach shows shed new light on both Cranachs and their workshop. The focus of each on their work executed in the service of the Ernestine dynasty, and in the locations where that work was carried out, gives them a special authenticity. The genius loci complements the genius of the art. To visit all three one would need a nearly week. It might be tempting to choose Weimar or the Wartburg if time was limited. Yet Gotha should really take priority. The Cranach show there is by far the best. And the Schloss Friedenstein Foundation has so much more to offer as well. To visit the Baroque Universe at Gotha is to experience the thrill of unanticipated marvels, a neglected treasure house which Martin Eberle and his team are so dramatically bringing back to life.

Joachim Whaley is Professor of German History and Thought at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of Gonville and Caius College. He is the author of Germany and the Holy Roman Empire 1493-1806, two volumes (2012).

Bild und Botschaft: Cranach im Dienst von Hof und Reformation, Stiftung Schloss, Friedenstein, Herzogliches Museum, Gotha, until 19 July (subsequently at the Museum Schloss, Wilhelmshöhe, 21 August-29 November)